Roth vs Traditional Accounts: Why the Decision Is About Timing, Not Guessing Rates

13.7 min read

Updated: Jan 8, 2026 - 02:01:09

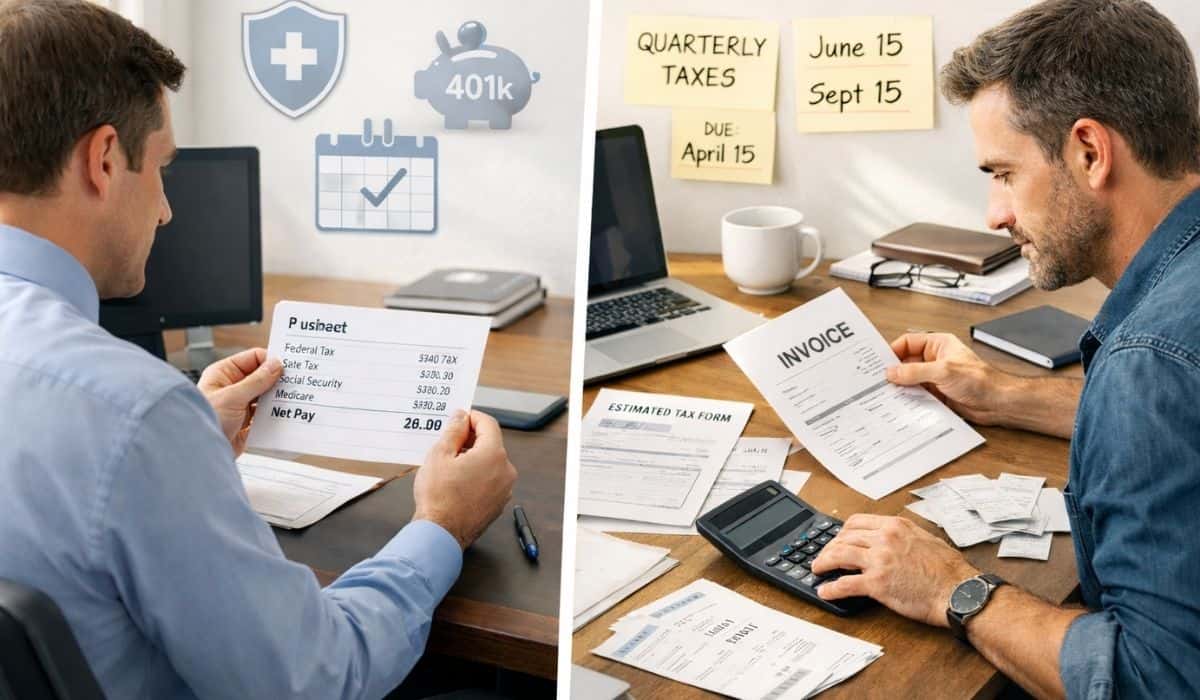

The Roth versus traditional retirement account decision is often framed as a bet on future tax rates, but that framing can miss the more practical point. The choice is primarily about managing lifetime marginal tax exposure, preserving flexibility, and reducing uncertainty using information you can actually know today. Traditional contributions defer taxes and provide immediate cash-flow relief, while Roth contributions lock in today’s tax treatment and can reduce future tax uncertainty on those dollars under current law. Many savers benefit from using both over time, adjusting contributions as income changes, and using Roth conversions strategically during lower-income years rather than trying to predict tax policy decades ahead.

- Current tax reality matters more than future guesses: Your known marginal rate today is actionable; predicting tax rates decades ahead is inherently uncertain.

- Taxable retirement income is layered: Social Security taxation, standard deductions, progressive brackets, and Medicare IRMAA mean withdrawals can interact in complex ways, making Roth flexibility valuable.

- Roth buys certainty; traditional preserves flexibility: Roth locks in today’s rate under current law and qualified-withdrawal rules, while traditional defers the decision to a future year that may be lower or higher.

- No decision is permanent: Many high earners use traditional accounts during peak years, then execute partial Roth conversions in early retirement before RMDs begin, depending on goals and tax situation.

- Diversification beats optimization: Holding both traditional and Roth assets can allow retirees to manage taxable income, Medicare premiums, and lifetime tax risk.

The question of whether to contribute to Roth or traditional retirement accounts appears frequently in personal finance discussions and is often framed as a comparison between your current tax bracket and your expected tax bracket in retirement. That comparison is directionally useful, but it oversimplifies a decision that involves more than guessing future tax rates. The choice also depends on timing, uncertainty, flexibility, and how contributions and withdrawals interact with the rest of your financial situation over time.

Understanding why the Roth versus traditional decision is not primarily about predicting future tax laws helps lead to more practical and informed choices. At its core, the decision is about managing lifetime marginal tax exposure, maintaining tax diversification, and preserving flexibility as income sources, withdrawal needs, and tax rules change. Framing the decision this way supports long-term financial goals without relying on uncertain forecasts about the future.

Present Versus Future Income: The Core Framework

The fundamental distinction between Roth and traditional contributions is about when taxes are paid on retirement savings: now, using current income, or later, through future withdrawals.

Traditional contributions reduce current taxable income, lowering taxes based on the taxpayer’s marginal rate at the time of contribution. The contributed amount grows tax-deferred for decades, and withdrawals, both original contributions and investment growth, are taxed as ordinary income. Under IRS rules governing traditional IRAs and employer plans, this structure tends to favor deferral when taxable income during working years is higher than taxable income during retirement.

Roth contributions are made with after-tax dollars. Income tax is paid upfront, after which contributions grow without ongoing taxation. If withdrawal rules are met, both contributions and all investment growth are distributed tax-free. Under IRS Roth IRA guidance, this structure tends to favor paying taxes earlier when current taxable income is lower, or when future taxable income may be higher or less predictable.

At first glance, the choice appears to require forecasting future tax rates. In practice, it is less about predicting tax policy and more about comparing present versus future income levels, flexibility, and how each account type fits into an overall financial strategy.

Why the “Guess Your Future Bracket” Approach Is Incomplete

The common advice to “use Roth if you expect higher tax rates in retirement and traditional if you expect lower rates” contains some truth, but it oversimplifies a decision that depends on far more than predicting a future tax bracket.

Tax Rates Are Only One Variable

Your effective tax rate in retirement is determined by total taxable income from all sources, not just withdrawals from one account. Social Security, pensions, traditional retirement account withdrawals, part-time work, rental income, interest, dividends, and capital gains all stack together and determine which tax brackets apply.

The standard deduction and progressive tax brackets also mean that a portion of retirement income is often taxed at relatively low rates. For 2024, a married couple filing jointly receives a $29,200 standard deduction. After that, taxable income is taxed at 10% on the first $23,200, then 12% on income from $23,201 to $94,300. The 22% bracket begins at $94,301. This means the 12% bracket spans $71,100, not $66,800, before higher rates apply.

Social Security taxation adds another important interaction. Depending on “provisional income,” up to 85% of Social Security benefits may be included in taxable income and then taxed at ordinary rates. Traditional IRA and 401(k) withdrawals generally increase provisional income, while qualified Roth withdrawals generally do not, which can make Roth funds more valuable even when the nominal tax bracket appears similar.

Medicare premiums further complicate the picture. IRMAA surcharges are based on modified adjusted gross income (MAGI). Taxable withdrawals from traditional accounts increase MAGI and can trigger higher Medicare premiums. Qualified Roth withdrawals typically do not affect MAGI, though Roth conversions are taxable and can increase MAGI, potentially causing IRMAA surcharges in the year they occur.

You Are Not Making a Permanent, One-Time Decision

The idea that you must choose either Roth or traditional for life is misleading. Many people contribute primarily to traditional accounts during high-income years, then shift toward Roth contributions or perform Roth conversions during lower-income periods, such as early retirement before required distributions begin.

The more accurate question is not “Roth or traditional forever?” but “Which option makes the most sense right now, and how can I preserve flexibility for future years?”

Predictability Versus Uncertainty

A more useful framing focuses on what you can control versus what remains uncertain.

What You Control: Current Tax Cost

With Roth contributions, you lock in today’s tax treatment under current law. You know your current marginal tax rate, you know the tax cost of the contribution, and you can reduce future income-tax uncertainty on that money.

Someone in the 22% marginal federal tax bracket contributing $7,000 to a Roth IRA in 2024 knows that the contributed dollars are taxed at that rate, about $1,540 of federal tax attributable to the contribution. Once contributed, both the principal and future growth can be withdrawn tax-free if qualified withdrawal rules are met under current law.

This certainty has value beyond simple tax-rate comparisons. It reduces exposure to higher future tax rates caused by legislative changes, personal circumstances that increase taxable retirement income, required minimum distributions, or interactions with other taxable income sources. While no tax treatment is completely immune to future policy changes, Roth accounts currently provide a higher level of predictability than tax-deferred withdrawals for qualified distributions.

What Remains Uncertain: Future Tax Treatment

Traditional contributions defer the tax decision to the future. You receive an immediate tax benefit today, but the eventual tax cost depends on factors that cannot be known with certainty at the time of contribution, including:

-

Tax rates at the time withdrawals occur

-

Total retirement income from all sources

-

How required minimum distribution rules affect taxable income

-

What tax provisions exist decades from now

-

State tax residence in retirement

This uncertainty is not inherently negative. It preserves flexibility and can work in your favor if future income is lower or withdrawals fall into lower tax brackets. But it does mean that the value of the tax deferral is not finalized until withdrawals actually occur, often 30 to 40 years after the contribution is made.

Why No Choice Is Universally “Best”

Personal finance advice often seeks universal rules: “always do X,” “never do Y.” Roth versus traditional decisions resist this simplification because optimal choices vary significantly based on individual circumstances.

When Roth Advantages Are Strongest

Roth contributions particularly favor:

- Early career workers in low brackets: Someone in the 10% or 12% bracket locks in low rates under current law. Even modest career progression can push future income into higher brackets, making current tax payment favorable.

- Those expecting substantial retirement income: High earners with pensions, substantial investment income, or other sources of retirement income may find traditional account withdrawals pushed into higher brackets by other income. Having Roth assets can avoid compounding taxable-income levels in retirement.

- People valuing certainty over flexibility: Some individuals prefer knowing their tax obligation is settled rather than optimizing for expected value across uncertain futures. Roth contributions can satisfy this preference.

- Those planning to leave assets to heirs: Roth accounts can stay in place without RMDs during the owner’s lifetime, allowing tax-free growth to continue and providing tax-free inheritance to beneficiaries under current rules if requirements are met.

- People expecting to live in high-tax states in retirement: Traditional withdrawals generally face state tax wherever you’re resident. Roth withdrawals are generally not subject to federal income tax if qualified; state treatment can vary. If retiring in California or New York rather than Florida or Texas, Roth advantages may increase.

When Traditional Advantages Are Strongest

Traditional contributions particularly favor:

- Peak earning years in high brackets: Someone in the 32% or 35% bracket gets substantial current tax savings that can be redirected to additional savings or debt reduction. If retirement income falls to 12% or 22% brackets, the arbitrage can be favorable.

- Those expecting lower retirement income: People who plan to reduce spending significantly in retirement, have no pension, will have modest Social Security, and expect to draw primarily from retirement accounts often face lower effective rates in retirement than during peak earning years.

- People with tight current cash flow: The tax savings from traditional contributions make the effective “cost” of saving lower. Someone who can’t afford to save after paying tax on income might save more if getting a current-year tax reduction.

- Those expecting to retire in no-tax or low-tax states: Someone working in California who will retire in Nevada benefits from traditional contributions that defer tax through the high-state years and pays it in the no-tax state.

- Savers who value flexibility over certainty: Traditional contributions preserve current cash flow flexibility while maintaining optionality about future withdrawals and potential Roth conversions at opportune times.

How This Decision Fits Into Broader Tax Strategy

The Roth versus traditional choice doesn’t exist in isolation, it connects directly to broader tax planning and long-term financial flexibility.

Multi-Account Diversification

Holding money in both traditional and Roth accounts provides flexibility that concentrating in only one type does not. A retiree with assets split between tax-deferred and tax-free accounts can manage taxable income more precisely by choosing which account to draw from each year.

Traditional withdrawals can be used to fill lower tax brackets, while Roth withdrawals can fund additional spending without increasing taxable income. This flexibility can help manage Social Security benefit taxation and reduce the risk of crossing Medicare IRMAA income thresholds, which are based on modified adjusted gross income. The value comes from optionality, having multiple levers to pull, rather than committing decades in advance to a single tax outcome.

Roth Conversions as a Planning Tool

Roth conversions allow taxpayers to shift money from traditional accounts to Roth accounts by paying income tax at the time of conversion. This can be useful when current income is temporarily lower than normal, such as during early retirement before required minimum distributions begin, after job loss, or during business downturns.

Market declines can also make conversions more efficient by lowering the taxable value of the converted amount. While there are no income limits or dollar caps on Roth conversions themselves, conversions increase taxable income in the year they occur and can trigger higher marginal tax rates or Medicare IRMAA in future years. The benefit is eliminating future tax on the converted amount and all subsequent growth under current rules if qualified withdrawal rules are met.

Coordination With Other Account Types

Retirement account decisions also interact with taxable accounts and asset location strategy. Investments that generate higher ongoing taxable income are often better held in tax-advantaged accounts, while tax-efficient investments can be placed in taxable or Roth accounts depending on the broader plan.

Roth accounts are especially valuable for assets with higher expected long-term growth because qualified withdrawals are completely tax-free. At the same time, tax savings from traditional contributions can free up cash flow that is redirected into Roth IRAs or taxable accounts, allowing investors to build a diversified mix of deferred, tax-free, and taxable assets without increasing out-of-pocket savings.

The Role of Employer Matching

Employer matching plays an important role in how workplace retirement contributions are structured and how taxes apply over time. Historically, employer matching contributions were required to be made on a pre-tax basis, even when employees chose Roth contributions for their own salary deferrals. In those cases, employer matches accumulated in traditional accounts and were taxed as ordinary income when withdrawn in retirement.

Under current law, employers are now permitted to offer Roth employer matching contributions. When this option is available, employer matches are included in the employee’s taxable income in the year of contribution and deposited into a Roth account. Many plans still default employer matches to traditional accounts, but the treatment now depends on plan design rather than a universal rule.

When employer matching contributions are made on a traditional basis, they create built-in tax diversification. An employee contributing entirely to Roth accounts still builds a traditional balance through employer contributions. Over a long career, these employer-funded amounts can represent a meaningful share of total retirement savings and will be taxed upon withdrawal.

In plans where employer matches remain pre-tax, this automatic traditional balance can make Roth employee contributions more attractive. The combination provides diversification across future tax treatments without requiring employees to split their own contributions. Where Roth matching is available, employees must instead evaluate whether paying tax upfront on employer contributions aligns with their broader retirement and tax planning strategy.

Why Current Circumstances Matter More Than Long-Term Predictions

The most practical approach to Roth versus traditional decisions focuses on current tax situation and near-term expectations rather than attempting to predict tax policy or personal circumstances 30-40 years in the future.

Current bracket position is known and actionable. Someone solidly in the 22% bracket with room before the 24% threshold faces different math than someone at the top of the 32% bracket or in the 10% bracket.

Near-term income expectations are reasonably predictable. Someone expecting a promotion, major bonus, or business growth in the next 2-3 years can plan around those changes. Someone planning a career break, returning to school, or reducing work hours can also incorporate that.

Current cash flow needs determine whether current tax savings from traditional contributions meaningfully affect ability to save. Someone who can max out retirement savings either way doesn’t face the same trade-off as someone for whom the tax savings make higher contributions feasible.

These current and near-term factors are knowable and actionable. Predictions about tax rates decades from now, personal tax situations after retirement, or whether you’ll live in a high-tax state 35 years from now are speculation. Building decisions on current reality rather than distant predictions can create more resilient strategies.

The Bigger Picture: Both Options Beat Taxable Accounts

While focusing on Roth versus traditional differences is valuable for optimization, both options provide significant advantages over taxable accounts.

Both generally eliminate current taxation during accumulation. Dividends, interest, and realized capital gains inside retirement accounts are not taxed annually, regardless of whether the account is Roth or traditional. This allows investments to compound more efficiently than in taxable accounts, where ongoing taxes create drag on long-term growth.

Both provide meaningful tax advantages on investment growth. Roth accounts deliver tax-free qualified withdrawals, while traditional accounts allow decades of tax-deferred growth before withdrawals are taxed as ordinary income. In contrast, taxable accounts are subject to taxes on investment income as it is generated and on gains when assets are sold.

Both support long-term retirement security. Contribution limits, withdrawal rules, and penalties on non-qualified distributions, particularly on earnings, are designed to discourage premature spending and preserve assets for retirement rather than short-term consumption.

The more sophisticated question is not whether to use retirement accounts, because for most people the answer is clearly yes, but how to allocate contributions between traditional and Roth options based on current income, tax exposure, and future flexibility needs. Neither choice is inherently wrong; each serves a legitimate role depending on individual circumstances.

Ultimately, the decision is less about finding a single “correct” answer and more about making informed choices that reflect current realities, preserve adaptability, and prioritize retirement security over perfect tax optimization across uncertain decades.