Marginal vs Effective Tax Rates: The Difference Most People Misunderstand

10 min read

Updated: Jan 5, 2026 - 01:01:10

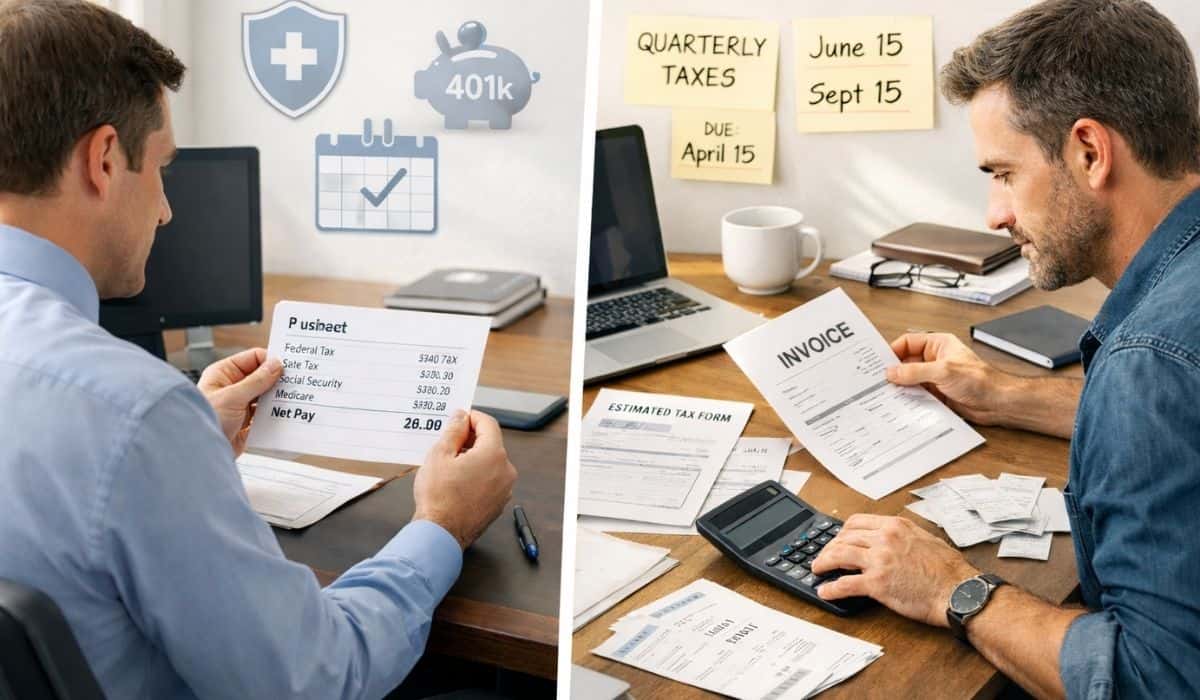

Moving into a higher federal tax bracket does not reduce your take-home pay. In the U.S. progressive tax system, higher rates apply only to the portion of income above each threshold, not to all income earned. Confusing marginal and effective tax rates leads people to turn down raises, avoid affordable retirement withdrawals, or mismanage tax strategy, costly mistakes that are entirely avoidable with a basic understanding of how brackets actually work.

- Marginal tax rate is the rate applied to your next dollar of income; it determines the tax cost or savings of decisions like earning more or making deductible retirement contributions.

- Effective tax rate is your total federal income tax divided by total income; it reflects your overall tax burden and is almost always lower than your marginal rate.

- Earning more money never causes previously earned income to be taxed at a higher rate, only the dollars above a bracket threshold face the higher rate.

- Tax planning decisions (401(k) vs. Roth, Roth conversions, bonus timing) should focus on marginal rates, not fear of “being in a higher bracket.”

- Income-based phaseouts can temporarily increase true marginal rates, but they do not overturn the core rule that higher income always leaves you better off after tax.

One of the most persistent and costly misunderstandings about taxation involves the difference between marginal and effective tax rates. This confusion leads to poor financial decisions: people turn down raises or bonuses, avoid retirement account withdrawals they can afford, or structure income inefficiently, all because they believe that “moving into a higher tax bracket” will reduce their take-home income.

In a progressive tax system, it won’t. Higher tax brackets apply only to income above each threshold, not to income already earned at lower levels. While other factors such as benefit phase-outs or additional taxes can affect net income in specific cases, tax brackets themselves do not penalize earning more. Understanding this distinction is fundamental to making informed financial decisions and evaluating tax strategy.

What Marginal Tax Rates Actually Are

Your marginal tax rate is the rate applied to your next dollar of taxable income. It’s the rate that sits at the top of your current income stack—the bracket you’ve most recently entered based on your taxable income level.

The United States uses a progressive tax system with multiple brackets. For 2024, a single filer faces seven federal income tax brackets: 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37%. These aren’t seven different tax systems, they’re layers that apply to different portions of income as it increases.

For example, in 2024, a single filer pays:

- 10% on taxable income from $0 to $11,600

- 12% on taxable income from $11,601 to $47,150

- 22% on taxable income from $47,151 to $100,525

- And so on through the remaining brackets

If your taxable income is $60,000, your marginal rate is 22%, that’s the bracket your income reaches into. But this absolutely does not mean you pay 22% on all $60,000.

What Effective Tax Rates Actually Are

Your effective tax rate is your total federal income tax divided by your total gross income. It represents the average rate you pay across all your income. In a progressive tax system, it is usually lower than your marginal rate unless all of your income falls within a single tax bracket.

Using the same example of $60,000 in gross income for a single filer in 2024 (after applying the standard deduction to arrive at taxable income), the actual tax calculation works like this:

- First $11,600 taxed at 10% = $1,160

- Next $35,550 (from $11,601 to $47,150) taxed at 12% = $4,266

- Remaining $12,850 (from $47,151 to $60,000) taxed at 22% = $2,827

Total tax: $8,253

Effective tax rate: 13.8%

This person’s marginal tax rate is 22%, but their effective tax rate is 13.8%. That gap exists because the progressive tax system applies different rates to different portions of income, rather than taxing all income at the highest bracket reached.

Why Earning More Never Means Taking Home Less

The most damaging misconception about tax brackets is the belief that earning additional income can push you into a higher bracket in a way that makes you worse off than before. People imagine that crossing a bracket threshold somehow applies the higher rate to all their income, resulting in a net loss.

This is mathematically impossible in a progressive tax system. Only the dollars above a bracket threshold are taxed at the higher rate. All income below that threshold continues to be taxed at the same lower rates as before.

Consider someone earning $47,000 in taxable income, just under the 22% bracket threshold of $47,150. If they receive a $1,000 bonus, the first $150 of that bonus is taxed at 12%, and the remaining $850 is taxed at 22%. The total federal income tax on the bonus is $205, meaning they keep $795 of the $1,000.

They do not suddenly pay 22% on their full income. They do not lose money overall. They simply pay different rates on different layers of income, exactly as designed. In a progressive system, effective tax rates rise gradually with income, while marginal rates apply only to the top portion of earnings.

Why Strategy Focuses on Where Income Lands, Not Fear of Brackets

Understanding the difference between marginal and effective rates changes how you think about financial decisions. The relevant question isn’t “what bracket am I in?” but rather “what’s the marginal rate on this next decision?”

When evaluating whether to contribute to a traditional 401(k) versus a Roth 401(k), your marginal rate matters because that’s the tax rate you avoid now with a traditional contribution. If you’re solidly in the 22% bracket, a traditional contribution saves you 22% on those dollars. If you expect to be in a lower bracket in retirement, that’s a meaningful benefit.

But effective rates matter too, particularly when thinking about retirement withdrawals. Someone with $50,000 in annual retirement income might worry about their 22% marginal bracket, but their effective federal rate could be around 12% because of the progressive structure. This distinction affects decisions about Roth conversions, retirement account withdrawal strategies, and whether to delay Social Security benefits.

The fear of brackets also leads people to make counterproductive decisions about income timing. Someone might defer a bonus from December to January, thinking they’re in danger of a higher bracket. But if they’re well within a bracket, say at $70,000 when the next threshold isn’t until $100,525, that deferral achieves nothing except pushing taxable income into a different year, which may or may not be beneficial depending on their complete tax situation across both years.

How Marginal Rates Affect Deduction and Credit Decisions

The value of deductions and the tax cost of additional income scale with your marginal tax rate, not your effective rate. This creates real and meaningful decision points.

A $1,000 contribution to a fully deductible traditional retirement account saves $220 in federal income tax if you’re in the 22% bracket, but only $120 if you’re in the 12% bracket. The same contribution produces a different tax benefit purely because of where that income falls within the bracket structure. This example always applies to traditional 401(k) contributions and applies to traditional IRAs only when the contribution is deductible.

This is why tax-deferred retirement savings often provides the greatest benefit to middle- and higher-income earners, not because they need the benefit more, but because the tax value of the deduction increases as marginal rates rise. Someone in the 12% bracket still benefits from traditional contributions, but the math changes materially at higher marginal rates.

The same logic applies to taxable investment income. A taxpayer in the 24% ordinary income bracket generally pays a 15% federal rate on long-term capital gains. A taxpayer in the 12% bracket pays 0% on long-term capital gains up to the top of that bracket. The same investment gain can therefore produce vastly different tax outcomes solely due to marginal-rate positioning.

The Hidden Complexity: Phaseouts and Marginal Rate Spikes

The standard tax bracket structure is only part of the marginal rate story. Various deductions, credits, and benefits phase out as income rises, creating effective marginal tax rates that can exceed the published bracket rates.

For example, the Child Tax Credit begins phasing out at $200,000 of adjusted gross income for single filers in 2024. Within that phaseout range, earning an additional dollar not only faces the taxpayer’s statutory marginal tax rate (often 22% or 24%) but also reduces the available credit, increasing the true marginal cost of that extra income above the bracket rate alone.

Similar effects occur with the student loan interest deduction, education credits, and other income-based benefits, each of which phases out over specific income ranges. When income falls inside one of these ranges, the marginal tax rate can temporarily spike before returning to the normal statutory rate once the phaseout is complete.

This complexity does not change the fundamental principle of progressive taxation, earning more money still leaves you better off after taxes. However, it does mean that published tax brackets do not always reflect the actual marginal rate on the next dollar of income. Understanding phaseouts explains why certain income ranges feel disproportionately taxed, even when statutory rates appear unchanged.

Common Errors That Come From Bracket Confusion

Misunderstanding marginal versus effective rates leads to several predictable mistakes:

- Turning down income opportunities: People decline overtime, refuse bonuses, or avoid contract work because they fear that “extra income will just go to taxes.” While taxes do reduce take-home pay, they never eliminate it entirely. The decision should be whether the after-tax income is worth the time and effort, not whether it’s taxed at all.

- Over-withholding from paychecks: Some people deliberately withhold far more than necessary, treating the tax system as a forced savings account, because they misunderstand their actual tax liability. This provides interest-free loans to the government rather than keeping money available throughout the year.

- Misunderstanding retirement withdrawal planning: Retirees sometimes avoid taking distributions from traditional retirement accounts because they think withdrawals will be taxed at their marginal rate in a way that makes them prohibitively expensive. But those withdrawals fill up lower brackets first, often resulting in effective rates much lower than feared.

- Poor timing of Roth conversions: Converting traditional IRA funds to Roth accounts makes sense in low-income years when the marginal rate is low. But people who focus on effective rates rather than marginal rates may convert in years when their marginal rate is actually quite high, paying more tax than necessary.

Why Both Rates Matter for Different Decisions

Marginal rates answer the question: “What happens to my next dollar?” They’re relevant for decisions about earning more, contributing to tax-deferred accounts, or generating additional taxable income.

Effective rates answer the question: “What’s my overall tax burden?” They’re relevant for understanding your total tax situation, comparing tax bills across years, or evaluating whether you’re generally paying what you expected relative to your income.

Both rates are real. Both matter. They just matter for different purposes. Effective rates tell you how much you paid. Marginal rates tell you how much the next decision will cost or save.

This distinction is particularly important in retirement planning. During accumulation years, marginal rates drive contribution decisions, traditional versus Roth accounts, whether to maximize contributions, how to time bonuses or stock compensation. During withdrawal years, effective rates matter more for understanding total tax burden on retirement income, though marginal rates still apply to decisions about additional withdrawals or conversions.

How This Connects to Broader Tax Strategy

Understanding marginal versus effective rates isn’t an isolated technical detail. It’s foundational to nearly every tax-aware financial decision.

When evaluating investment account types, marginal rates determine the value of tax deferral. When considering debt payoff versus investing, marginal rates matter when investment returns or interest costs are tax-affected, but must be weighed alongside after-tax returns and whether debt interest is deductible. When planning income across years, through retirement contributions, investment gain timing, or self-employment income management, marginal rates in each year determine whether shifting income makes sense.

The progressive tax structure creates planning opportunities precisely because not all income is taxed equally. Someone who understands how to fill lower brackets efficiently, coordinate income timing when alternatives exist, and evaluate whether paying tax at current rates is preferable to deferring into potentially higher future rates has a structural advantage.

That advantage doesn’t come from tricks or loopholes. It comes from understanding how the system works and making decisions with that knowledge in mind.