How Taxes Affect Long-Term Investment Returns

13.4 min read

Updated: Jan 2, 2026 - 00:01:18

Investment performance is almost always quoted in pre-tax terms, but for assets held in taxable brokerage accounts, what matters is how much of the return actually remains invested after taxes. Ongoing taxes on dividends, interest, and realized capital gains create tax drag, a compounding friction that can reduce long-term wealth by six figures over multi-decade horizons, even when pre-tax returns are identical. The gap between headline performance and real outcomes is driven by turnover, income type, and account structure, not just market returns.

- Tax drag interrupts compounding: Each dollar paid in taxes on dividends, interest, or realized gains is a dollar that no longer compounds. Over 20–30 years, even a 0.5% annual tax drag can reduce ending wealth by 10–15%.

- Turnover matters more than headline returns: High-turnover active funds often distribute taxable gains annually, while low-turnover index funds and ETFs minimize realizations, improving after-tax outcomes.

- Income type drives tax cost: Bond interest is typically taxed at ordinary rates (up to 37% federally), while qualified dividends and long-term capital gains benefit from preferential rates, making equities generally more tax-efficient in taxable accounts.

- Account structure changes everything: Tax-deferred and Roth accounts eliminate ongoing tax drag during accumulation, making them ideal for tax-inefficient assets like bonds or REITs.

- After-tax returns determine real outcomes: Two strategies with identical pre-tax returns can differ by over $100,000 in long-term results solely due to tax efficiency, underscoring why after-tax analysis is essential for realistic financial planning.

Investment returns are almost always discussed in pre-tax terms. A fund advertises a 10% annual return. A stock appreciates 15% in a year. An index averages 8% over a decade. These figures describe growth before accounting for the taxes generated in the process of earning those returns.

For taxable accounts, standard brokerage accounts held outside of IRAs, 401(k)s, and other tax-advantaged structures, the pre-tax return is only part of the outcome. Taxes on dividends, interest, and realized capital gains create friction that reduces the wealth an investor ultimately keeps. Understanding how this tax friction works, why it varies across investment strategies, and what drives the gap between pre-tax performance and after-tax results is essential for realistic long-term financial planning.

Compounding Versus Friction

Investment returns compound over time. Each year’s gains generate additional gains in subsequent years, creating exponential growth. A $10,000 investment earning 8% annually grows to $21,589 after ten years and $46,610 after twenty years, assuming no withdrawals and no taxes.

In taxable accounts, taxes introduce friction into this compounding process. Whenever investment income is taxed, through interest, dividends, or realized capital gains, a portion of the return is removed from the account. That portion no longer compounds in future years, reducing the long-term growth of the investment even if the pre-tax return remains the same.

Consider two identical $10,000 investments earning 8% annually for twenty years. One is held in a tax-deferred IRA, where no taxes are paid during the accumulation phase. The other is held in a taxable account that generates taxable investment income each year, creating an ongoing tax cost. Although both investments earn the same pre-tax return, the taxable account retains less capital to compound because some of each year’s return is diverted to taxes along the way.

As a result, the tax-deferred account grows to the full $46,610 during the accumulation period. The taxable account ends with a lower after-tax value because compounding is repeatedly interrupted. Research from firms such as Vanguard has shown that, over long holding periods, taxes can materially reduce ending portfolio values, with the magnitude of the reduction depending on the investment’s tax efficiency and the investor’s tax rates.

The difference is not the headline return, both investments achieved 8% annual growth before tax. The difference is how much of that growth remained invested and available to compound versus how much was lost to taxes each year. This reduction in growth is known as tax drag.

Tax drag is not uniform. It varies based on the type of income an investment produces, how frequently taxable events occur, the investor’s marginal tax rates, the holding period, and the account structure in which the investment is held.

Turnover and Distribution: The Hidden Tax Generators

Portfolio turnover, how frequently securities within a fund are bought and sold, has a direct impact on tax efficiency in taxable accounts. Higher turnover increases the number of realized transactions, which can generate taxable capital gains distributions even when an investor never sells their fund shares, reducing the portion of returns that can continue compounding.

Actively managed mutual funds often have turnover rates in the 60% to 100% range annually, meaning a large share of holdings may be replaced each year. When securities are sold at a gain inside the fund, those gains are passed through to shareholders as capital gains distributions. These distributions must be reported and taxed in the year they occur, regardless of whether the investor initiated a sale.

Index funds, by contrast, typically maintain much lower turnover. Many broad-market index funds operate with annual turnover below 5%, trading primarily when the underlying index changes. This limited trading activity results in fewer realized gains and fewer taxable distributions, allowing more of the return to compound without tax interruption.

Research published by the Investment Company Institute shows that index funds generate lower tax costs than actively managed funds. This difference is driven less by pre-tax performance and more by structural factors, especially lower turnover, that reduce taxable events.

Source: ICI

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are often even more tax-efficient than mutual funds due to their in-kind creation and redemption process. When ETF shares are redeemed, the fund can transfer low-basis securities instead of selling them, frequently avoiding capital gains realization. This structure limits distributions, particularly for broadly diversified equity ETFs, improving after-tax returns.

Why Pre-Tax Returns Can Mislead

Marketing materials, performance reports, and financial media almost always present pre-tax returns. This creates a systematic bias toward strategies and products that appear attractive before taxes but may deliver weaker results after taxes for investors using taxable accounts.

An actively managed fund returning 11% annually pre-tax may look superior to an index fund returning 10%. However, if the active fund distributes a larger portion of its return each year, such as 2% in taxable capital gain and dividend distributions, while the index fund distributes only 0.5%, the after-tax outcome can look very different. Taxes on these distributions reduce the amount of return left to compound, even when the investor never sells their fund shares.

Using simplified assumptions for illustration, with long-term capital gain and qualified dividend distributions taxed at 15%, the active fund would lose roughly 0.3% annually to taxes on distributions, while the index fund would lose about 0.1%. That reduces the active fund’s effective return to approximately 10.7% and the index fund’s to about 9.9%. The original 1% pre-tax advantage narrows meaningfully once taxes are considered, and can shrink further for investors in higher tax brackets or funds with higher turnover.

These calculations are simplified, but the principle is robust: pre-tax returns do not reflect what investors actually keep. For investments held in taxable accounts, after-tax returns determine long-term wealth accumulation. Yet after-tax performance data remains far less prominent than pre-tax figures in fund marketing and performance comparisons.

The Tax Characteristics of Different Investment Types

Different investments generate different types of taxable income, each with distinct tax treatment. This variation means that two investments with identical pre-tax returns can produce meaningfully different after-tax outcomes.

Bonds and Interest Income

Bonds generate interest income, which is generally taxed as ordinary income at marginal tax rates of up to 37%, with an additional 3.8% net investment income tax potentially applying for higher-income investors. For someone in the 32% federal bracket, a bond yielding 4% provides an after-tax return of 2.72%, meaning a substantial portion of the return is lost to taxes before compounding.

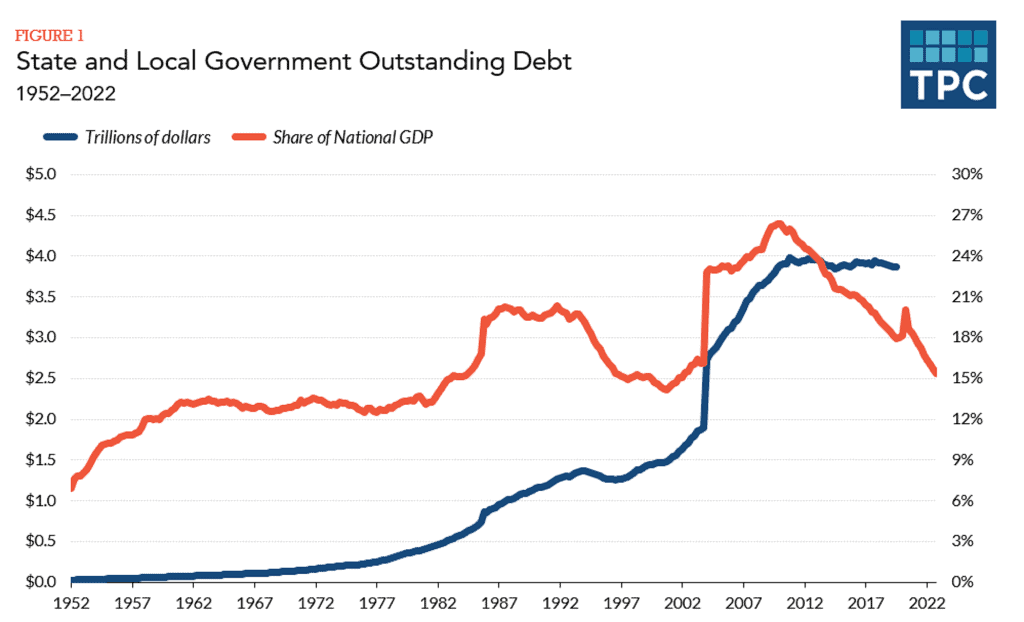

Tax-exempt municipal bonds issued by state and local governments often pay interest that is exempt from federal income tax, though state taxation and alternative minimum tax rules can apply in some cases. For higher-bracket taxpayers, a municipal bond yielding 3% tax-free can provide a higher after-tax return than a taxable bond yielding 4.5%. This relationship depends on marginal tax rates, which is why municipal bonds tend to be more attractive to investors facing higher ordinary income taxes.

Source: Tax Policy Center

Because bond interest is taxed annually at ordinary rates, bonds are often well-suited for tax-deferred accounts such as IRAs and 401(k)s, where interest can compound without current taxation. Stocks, which tend to generate returns through capital appreciation taxed at preferential rates when realized, are often more tax-efficient when held in taxable accounts.

Dividend-Paying Stocks

Dividends come in two forms: qualified and non-qualified. Qualified dividends are taxed at the same preferential rates as long-term capital gains, 0%, 15%, or 20% depending on income, while non-qualified dividends are taxed as ordinary income.

Most dividends from U.S. corporations and certain foreign corporations qualify for preferential treatment if holding period requirements are met, though exceptions exist. This makes dividend-paying stocks generally more tax-efficient than bonds, though less tax-efficient than growth-oriented investments that generate little or no current income.

A stock paying a 3% dividend yield taxed at 15% provides an after-tax yield of 2.55%. The same 3% return generated as bond interest taxed at 24% produces an after-tax yield of 2.28%. Identical pre-tax yields lead to different after-tax outcomes solely because of tax treatment.

Growth Stocks and Index Funds

Investments that generate minimal current income, such as growth stocks that pay no dividends and broad index funds with low distribution rates, benefit from tax deferral. Most of the return accumulates as unrealized capital gains, which are not taxed until the investment is sold.

An index fund that appreciates 8% annually but distributes only 0.5% creates current tax liability on just that 0.5%, allowing the remaining return to compound without interruption. When gains are eventually realized after more than one year, they are generally taxed at preferential long-term capital gains rates.

The combination of low distributions, deferral of taxation, and favorable rates on realized gains makes these investments particularly tax-efficient in taxable accounts. Over long time horizons, this efficiency can meaningfully increase after-tax wealth compared with investments that generate regular taxable income.

The Long-Term Impact of Tax Drag

Small differences in annual tax drag compound into large differences over long investment horizons. A 0.5% difference in annual after-tax returns produces approximately a 9–10% difference in ending wealth over twenty years and about a 14–15% difference over thirty years, assuming steady compounding.

Consider someone investing $500 per month for thirty years, earning an average 8% annual pre-tax return. With minimal tax drag of 0.3% annually, consistent with a low-turnover, tax-efficient index fund strategy, the effective after-tax return is approximately 7.7%. At this rate, the portfolio grows to roughly $700,000 over thirty years.

With moderate tax drag of 1.5% annually, reflecting frequent taxable distributions from higher-turnover active funds and less tax-efficient holdings, the effective return falls to approximately 6.5%. Under the same contribution pattern and time horizon, the ending portfolio value is approximately $580,000.

The difference, about $120,000, arises from tax efficiency alone, assuming identical pre-tax performance, contribution behavior, and investment risk. The entire gap reflects how much of each year’s return was diverted to taxes rather than remaining invested to compound.

The lesson is not that taxes should dominate investment decisions. Expected returns, risk tolerance, and long-term goals matter more than tax efficiency. However, among otherwise similar investments held in taxable accounts, properly accounting for tax drag creates a material and measurable difference in long-term outcomes.

Why Long-Term Planning Matters More Than Short-Term Tax Focus

Tax-efficient investing does not mean making every decision based on tax consequences. It means understanding how taxes affect returns over long investment horizons and making informed trade-offs.

In some situations, accepting higher tax costs makes sense:

- Rebalancing to maintain target allocations may require selling appreciated assets in taxable accounts and realizing gains, but maintaining appropriate risk exposure can outweigh the tax cost.

- Realizing losses to offset gains through tax-loss harvesting involves selling investments at a loss to reduce current or future tax liability. When done strategically, harvested losses can offset capital gains or limited amounts of ordinary income.

- Taking gains in low-income years can also be beneficial. Investors with low taxable income, often before required minimum distributions or taxable Social Security benefits begin, may be able to realize long-term capital gains at 0% or 15% rates.

- Consolidating accounts or simplifying holdings in taxable accounts may require realizing gains, but the planning and operational benefits can justify the tax cost.

The key is making these decisions consciously, understanding the tax consequences, and evaluating whether the benefits justify the costs. This differs from ignoring taxes entirely or making tax avoidance the primary objective regardless of other factors.

Tax-Deferred and Tax-Free Accounts Change Everything

The discussion so far focuses on taxable accounts because that’s where tax drag occurs during accumulation. But most long-term investors hold significant assets in tax-advantaged accounts, 401(k)s, traditional IRAs, Roth IRAs, 403(b)s, and similar structures.

Tax-deferred accounts, such as traditional 401(k)s and IRAs, eliminate ongoing tax drag during the accumulation phase. Returns compound without current taxation, allowing more capital to remain invested over time. Taxes are paid later when funds are withdrawn, typically in retirement. This structure makes these accounts well suited for investments that would otherwise generate high tax costs in taxable accounts, including bond funds, REITs that generate ordinary income, and higher-turnover actively managed funds. While taxes are deferred rather than eliminated, uninterrupted compounding during accumulation can materially improve long-term outcomes.

Tax-free accounts, including Roth IRAs and Roth 401(k)s, also avoid tax drag during accumulation and allow qualified withdrawals to be made tax-free if the rules are followed. This makes Roth accounts highly tax-efficient, though contributions do not reduce current taxable income. As IRS guidance explains, the trade-off between traditional and Roth accounts depends on current versus expected future tax rates. Under current law, Roth 401(k)s do not require lifetime minimum distributions.

The existence of these account types means tax-efficient investing in taxable accounts matters most for savings beyond tax-advantaged contribution limits. An investor contributing near the annual maximum to a 401(k) and an IRA can shelter a large portion of savings from ongoing taxation each year. Additional savings typically flow into taxable accounts, where tax efficiency becomes more relevant.

How This Connects to Overall Financial Strategy

Understanding tax drag on investment returns plays an important role throughout the wealth-building process, influencing how assets are structured, selected, and ultimately withdrawn. Tax efficiency is not a standalone tactic but a portfolio-wide consideration that affects long-term outcomes.

Asset location strategy focuses on placing tax-inefficient investments, such as bond funds or high-turnover strategies, inside tax-deferred or tax-free accounts, while holding more tax-efficient investments in taxable accounts. This approach improves overall after-tax portfolio returns, though optimal placement also depends on expected growth rates and time horizon, not taxes alone.

Fund selection extends beyond expense ratios and headline returns to include tax efficiency factors such as turnover rates, historical capital-gain distributions, and investment structure. Funds with lower turnover generally generate fewer taxable events, allowing a greater portion of returns to remain invested and compound over time. Investment structure also matters, as different vehicles distribute income and gains differently.

Withdrawal planning in retirement requires careful coordination between account types. Strategies often begin with taxable accounts, where withdrawals primarily realize long-term capital gains. While these gains still increase adjusted gross income, they may be taxed at preferential or even zero federal rates depending on total income, making them relatively tax-efficient in certain situations compared with ordinary income withdrawals.

Estate planning further highlights the importance of tax structure. Appreciated assets held in taxable accounts generally receive a step-up in basis at death, potentially eliminating capital gains taxes for heirs. Traditional retirement accounts do not receive this adjustment, and distributions are taxed as ordinary income, making asset location decisions relevant even beyond the investor’s lifetime.

The unifying principle is that after-tax returns, not pre-tax returns, determine actual wealth accumulation. Each percentage point preserved from taxes remains invested and compounds over time. Effective tax awareness does not require complex strategies or aggressive minimization, only an understanding of how investments interact with the tax system and informed decisions about where assets are held.