Estimated Taxes Explained: How Self-Employed Payments Actually Work

14.4 min read

Updated: Jan 8, 2026 - 02:01:37

Estimated taxes exist because the U.S. operates on a pay-as-you-go tax system. When income isn’t subject to withholding, such as self-employment, freelance, rental, or investment income, the IRS requires taxpayers to make quarterly payments so tax is paid as income is earned, not deferred until filing season. If you expect to owe at least $1,000 after withholding and credits, IRS Publication 505 generally indicates either sufficient withholding or estimated payments may be needed. The system doesn’t demand perfect forecasts; it rewards planning, timely payments, and use of safe-harbor rules to help avoid penalties while managing cash flow.

- Quarterly payments are about timing, not precision. Estimated payments are due April 15, June 15, September 15, and January 15, covering unequal periods. Most taxpayers pay roughly equal amounts unless they use the annualized income method described in Form 1040-ES instructions.

- Safe harbors can eliminate penalty risk even with inaccurate estimates. You may avoid underpayment penalties if you pay 90% of current-year tax, 100% of prior-year tax (110% if AGI exceeded $150,000), or owe under $1,000, per IRS estimated tax penalty guidance.

- Underpayment penalties are interest-like, not punitive. When safe harbors aren’t met, penalties accrue by quarter based on how long tax went unpaid, using rates tied to the federal short-term rate plus 3%, as calculated on Form 2210.

- Withholding can replace estimated payments. W-2 withholding is treated as paid evenly throughout the year, making it a powerful planning tool for gig workers or households with mixed employment and self-employment income.

- Cash-flow systems matter more than exact math. Separating tax reserves, targeting prior-year safe harbor amounts, and reviewing results quarterly can reduce stress and help prevent surprise balances, an issue widely noted by self-employment groups such as the National Association for the Self-Employed.

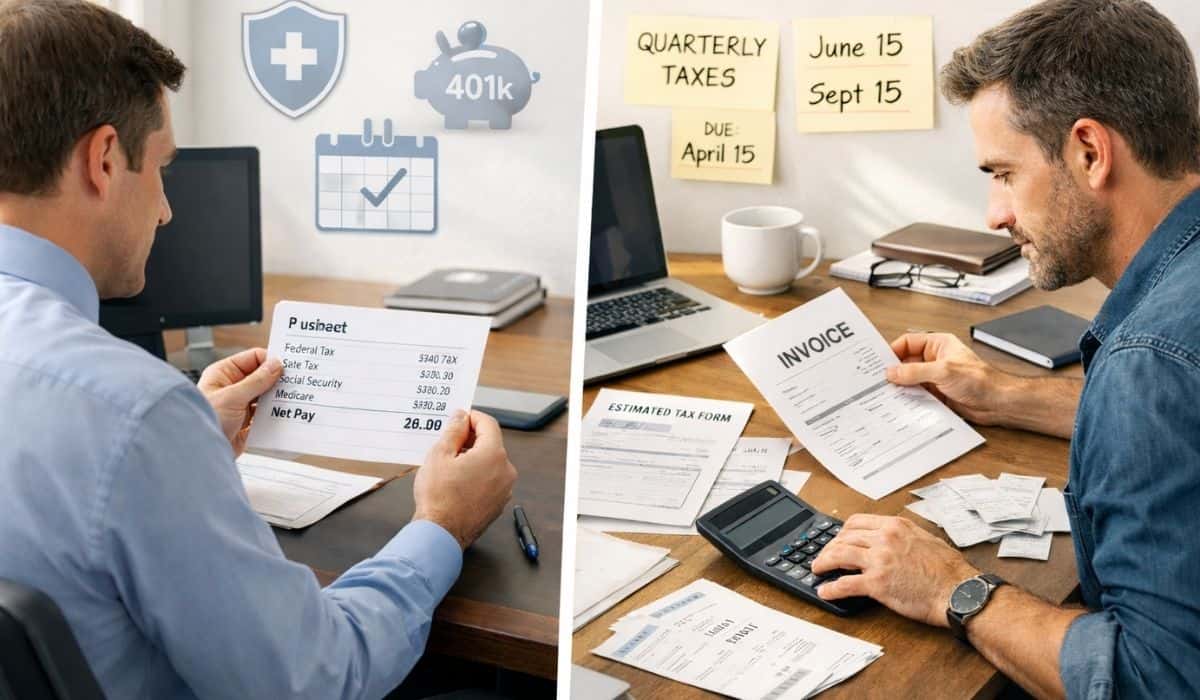

For employees, taxes are largely invisible. Withholding occurs automatically with each paycheck, and many people experience tax season primarily as filing a return to determine whether they receive a refund or owe a balance. Self-employed individuals, freelancers, and independent contractors operate under a different system: periodic estimated tax payments that require active planning, multiple remittances during the year, and personal responsibility for estimating and paying tax obligations.

This system often creates confusion and anxiety, particularly for those new to self-employment. Understanding why estimated taxes exist, how the payment schedule actually works, and how IRS safe-harbor rules and underpayment penalties apply when estimates are inaccurate helps reduce unnecessary stress and provides a practical framework for managing tax obligations throughout the year. This information is general educational content and is not tax advice.

Why Estimated Taxes Exist

The U.S. tax system operates on a pay-as-you-go basis. Tax obligations are intended to be paid throughout the year as income is earned, not as a single lump sum when filing an annual return. For employees, withholding from each paycheck generally satisfies this requirement automatically. For income not subject to withholding, estimated tax payments serve the same purpose.

According to IRS Publication 505, taxpayers must either have sufficient withholding or make estimated tax payments if they expect to owe at least $1,000 in federal tax after subtracting withholding and refundable credits. As a result, individuals with modest self-employment or other non-withheld income alongside W-2 wages may not need to make estimated payments if their wage withholding covers the total tax liability.

Estimated tax requirements commonly apply to income not subject to withholding, including self-employment income, investment income, rental income, and certain retirement distributions when withholding is not elected. For self-employed individuals, estimated payments generally cover both income tax and self-employment tax, which represents the self-employed equivalent of Social Security and Medicare taxes.

The system exists to enforce the pay-as-you-go structure of federal taxation and to ensure tax is collected as income is earned rather than deferred until filing season. Spreading payments across the year reduces the risk of large year-end balances and aligns tax payments more closely with ongoing cash flow.

How the Payment Cadence Works

Estimated taxes are paid quarterly, though the quarters are not equal calendar quarters. The IRS sets specific payment deadlines that follow this pattern:

- First quarter payment covers January 1 through March 31, due April 15

- Second quarter payment covers April 1 through May 31, due June 15

- Third quarter payment covers June 1 through August 31, due September 15

- Fourth quarter payment covers September 1 through December 31, due January 15 of the following year

The unequal periods reflect statutory deadlines tied to the tax filing calendar rather than business or financial quarters. The second period spans only two months, while the others cover roughly three, which often creates confusion about how much should be paid with each installment.

In practice, the IRS does not require precise matching of each payment to income earned during that specific period unless a taxpayer uses the annualized income installment method. Taxpayers with relatively steady income typically pay roughly equal amounts each quarter and remain compliant under safe harbor rules. Those with uneven or seasonal income, such as a tax preparer earning most income early in the year or a business concentrated in the holiday season may adjust payment amounts, but doing so accurately generally requires applying the annualized income method to help avoid underpayment penalties.

Calculating Estimated Payment Amounts

The IRS provides Form 1040-ES with worksheets for calculating estimated tax obligations. The process involves:

- Estimating expected adjusted gross income for the full year

- Calculating estimated deductions to arrive at taxable income

- Applying tax brackets to determine income tax

- Adding self-employment tax (15.3% applied to 92.35% of net self-employment income, with half deductible in calculating AGI)

- Subtracting any withholding or credits

- Dividing the result by four (or adjusting for unequal income timing)

This calculation requires projecting income an entire year in advance, which for many self-employed individuals is inherently uncertain. New businesses, variable client demand, project-based work, and economic volatility all make accurate annual projections difficult.

The IRS allows taxpayers to update estimates each quarter based on actual year-to-date results and revised projections for remaining months. Someone who overestimated income early in the year can reduce later payments. Someone whose income exceeds expectations can increase subsequent payments to limit or avoid underpayment penalties, subject to quarterly timing rules.

What Happens When Estimates Are Inaccurate

Estimated tax payments are exactly that, estimates. The IRS expects reasonable attempts at accuracy, not perfect foresight. Several provisions address the inevitable reality that projections won’t match actual results.

Safe Harbor Provisions

The IRS provides safe harbor rules that prevent underpayment penalties even if estimates prove substantially inaccurate. Taxpayers who meet any of these conditions avoid penalties:

- Pay at least 90% of the current year’s total tax liability through withholding and estimated payments

- Pay at least 100% of the prior year’s total tax liability (110% if adjusted gross income exceeded $150,000)

- Owe less than $1,000 in tax after subtracting withholding and credits

According to the IRS guidance on estimated tax penalties, the prior-year safe harbor is particularly valuable for people whose income fluctuates significantly. By paying 100% of last year’s tax (either through withholding or estimated payments), taxpayers may avoid penalties even if current year income increases.

This provision creates a planning strategy: in years following low-income years, the safe harbor amount is modest and easier to meet. In years following high-income years, the safe harbor amount is larger but can still protect against penalties even if current-year income drops substantially.

Underpayment Penalties

When safe harbor requirements aren’t met and tax owed at filing time exceeds $1,000, underpayment penalties may apply. These penalties are calculated based on how much was underpaid and for how long. The penalty rate equals the federal short-term rate plus 3 percentage points, and it can change over time.

Importantly, these penalties aren’t simply annual rates applied to the full shortfall. The IRS calculates underpayment for each quarter separately, which means paying late in the year doesn’t necessarily compensate for underpayment early in the year. Someone who makes no payments all year and then pays the full amount in January will still generally face penalties for the periods when payment should have occurred.

The penalty structure creates an incentive to pay throughout the year rather than deferring everything until April. However, the penalties are generally designed to function more like interest on late payments than severe punitive measures. For someone who significantly underestimates income and owes $10,000 in unexpected tax, the penalty might add hundreds of dollars depending on timing and the applicable rates, which is meaningful but typically not catastrophic.

Overpayment Outcomes

When estimated payments exceed actual tax liability, the excess becomes a refund when filing the annual return. The IRS generally does not pay interest on overpayments (except in narrow circumstances involving delayed refunds), which means excessive estimated payments can function as interest-free loans to the government.

This creates a trade-off: overpaying reduces penalty risk and can provide a forced savings mechanism, but ties up capital that could be used for business operations or invested elsewhere. Underpaying preserves cash flow and potentially avoids tying up funds unnecessarily, but can increase the risk of penalties and create a larger payment obligation at filing time.

There’s no universally correct approach, the optimal balance depends on cash flow needs, income predictability, risk tolerance, and whether having forced tax reserves helps or hinders financial management.

Why Planning Matters More Than Precision

The estimated tax system generates anxiety partly because it appears to demand precision that is often impossible to achieve. Income for self-employed individuals is inherently variable and difficult to project months in advance. Business expenses are not perfectly predictable. Personal deductions and credits may depend on circumstances that are not known until year-end.

However, the system does not actually require perfect accuracy. It requires that taxpayers either pay sufficient tax by required deadlines or meet established safe harbor thresholds to help avoid underpayment penalties. This distinction matters because it shifts the focus away from achieving exact forecasts and toward managing obligations in a way that balances cash flow, compliance, and penalty avoidance.

Quarterly Reviews Instead of Annual Projections

Rather than attempting to project full-year income in January, many self-employed individuals benefit from quarterly reviews that calculate actual year-to-date income and project the remaining months based on current information. This approach allows estimates to adjust as reality unfolds instead of relying on fixed assumptions made early in the year that may no longer be accurate by midyear.

Form 1040-ES describes the Annualized Income Installment Method, which permits estimated tax payments that vary by quarter based on when income is actually earned. According to the IRS instructions for Form 2210, taxpayers with uneven or seasonal income can use this method to calculate required installments based on cumulative income through each payment period, potentially reducing required payments during lower-income quarters.

This flexibility allows taxpayers who earn a disproportionate share of their income earlier in the year, such as 60% of annual income in the first two quarters, to make higher payments during those periods and reduce penalty risk later, rather than being constrained by the standard approach of paying equal installments regardless of income timing.

Cash Flow Management Strategies

Effective estimated tax management often depends more on cash flow discipline than on complex calculations.

Separate accounts dedicated to tax reserves help ensure funds are available when payments come due. Many self-employed individuals automatically transfer a percentage of each client payment, often in the range of 25% to 35% depending on tax situation, into an account used solely for tax payments.

Conservative estimates in early quarters can provide a buffer against higher-than-expected income later in the year. Slight overpayment in Q1 and Q2 creates flexibility and can reduce stress if income in Q3 or Q4 exceeds projections.

Prior-year safe harbor targeting offers certainty for individuals with fluctuating income. Paying at least 100% of the prior year’s total tax liability (or 110% if adjusted gross income exceeded $150,000) through timely estimated payments can help avoid underpayment penalties regardless of how much current-year income increases.

Industry research and surveys from organizations such as the National Association for the Self-Employed indicate that cash flow discipline around tax obligations is one of the most common challenges faced by new independent contractors, often more difficult than the calculations themselves. Establishing systematic processes early helps prevent situations where payment deadlines arrive without sufficient funds available.

The Interaction With Withholding

Self-employed individuals who also have W-2 employment, an increasingly common arrangement in the gig economy, can use federal income tax withholding from wages to cover some or all of their total tax obligation, including tax attributable to self-employment income. This approach can reduce or eliminate the need to make separate quarterly estimated tax payments, provided total withholding and payments are sufficient.

For underpayment penalty purposes, federal income tax withholding from W-2 wages is treated as paid evenly throughout the year, regardless of when the withholding actually occurs. This differs from estimated tax payments, which are credited only as of the dates they are made. As a result, an individual who works as a W-2 employee from January through August and then becomes fully self-employed in September could increase W-4 withholding during the employment period to cover expected tax on self-employment income earned later in the year. That withholding is deemed paid ratably across all quarters, potentially reducing or avoiding underpayment penalties even though the self-employment income is earned in the final months.

This treatment creates legitimate planning flexibility for individuals transitioning between employment and self-employment, as well as for married couples filing jointly. In a joint return, one spouse’s W-2 withholding can be adjusted to cover household tax obligations arising from the other spouse’s self-employment income, allowing compliance with pay-as-you-go requirements without relying on separate quarterly estimated tax payments.

State Estimated Tax Requirements

Most states with income taxes require estimated payments under pay-as-you-go systems similar to federal rules, though thresholds, safe harbor provisions, and payment schedules often differ. Some states provide limited exceptions that allow annual payments rather than quarterly, typically for small balances, certain income types, or specific taxpayer categories, while others use different due dates or penalty calculations.

For self-employed individuals operating across state lines, such as remote workers serving clients in multiple states or professionals with multi-state practices, state tax obligations can become complex. Many states require nonresidents to make estimated payments on income sourced to that state when withholding or pass-through entity withholding does not fully cover the tax. Other states mitigate individual estimated payment requirements through mechanisms such as composite returns or mandatory withholding at the entity level. Reciprocal agreements can simplify compliance for wage income earned across state lines, but they generally do not apply to self-employment or business income.

The Tax Foundation tracks state tax structures and notes that nine states levy no broad-based individual income tax, eliminating personal income tax estimated payment requirements entirely. In states that do impose income tax, understanding state-specific estimated tax rules alongside federal requirements helps prevent unexpected balances and penalties at the state level.

When Professional Help Makes Sense

Many self-employed individuals successfully manage estimated taxes themselves, particularly those with relatively stable income and straightforward business structures. However, certain situations make professional assistance more practical.

- First year of self-employment involves learning new systems while establishing a business. Professional guidance can help set up estimated payments, bookkeeping practices, and compliance correctly from the start.

- Highly variable income that makes projections difficult can benefit from professional experience with the annualized income installment method and payment timing strategies that can reduce underpayment penalties.

- Multiple income sources, including W-2 wages, self-employment income, investment income, and rental income, increase complexity when calculating total tax liability and coordinating withholding with estimated payments.

- Multi-state income can create additional state filing and estimated payment requirements based on residency and source-of-income rules, which vary by state and are often easier to manage with professional support.

The business-related portion of professional tax assistance, whether from a CPA, enrolled agent, or tax attorney, is generally deductible and can help reduce penalties, improve cash-flow planning, and provide confidence that obligations are being handled correctly.

The Bigger Picture: Estimated Taxes as Part of Financial Management

Estimated tax payments aren’t a standalone obligation, they’re one component of broader financial management for self-employed individuals. Understanding how they work helps integrate tax planning with business operations, pricing decisions, and personal financial goals.

Pricing considerations for self-employed work should account for the full tax burden, including both self-employment tax and income tax, not just gross rates. Someone targeting a specific after-tax income needs to price services high enough to cover direct costs as well as a meaningful portion of revenue that will ultimately go to taxes, a range that commonly falls between 25% and 40% depending on income level, deductions, and state taxes.

Cash flow smoothing through systematic tax reserves helps prevent the feast-or-famine pattern where large client payments feel like windfalls until quarterly payments come due and claim a substantial share of available cash. Setting aside a consistent percentage of income for taxes transforms irregular obligations into predictable expenses.

Retirement contributions also interact with estimated taxes. Contributions to SEP-IRAs or solo 401(k)s can reduce taxable income and therefore lower income tax liability, though they generally do not reduce self-employment tax. Incorporating planned contributions into tax projections, especially when using annualized income calculations, can improve estimate accuracy and prevent overpayment.

The estimated tax system isn’t designed to be punitive. It’s structured to collect taxes throughout the year in a way that mirrors employee withholding. While it requires active management and adds administrative complexity, understanding how it works can turn estimated taxes from a source of anxiety into a manageable part of self-employment financial operations.