The Hidden Cost of Free Checking: What Your Bank Actually Makes From Your Account

10.8 min read

Updated: Dec 25, 2025 - 12:12:50

“Free checking” accounts typically have no monthly fee or minimum balance, but they are far from unprofitable. Banks earn money through a combination of interest rate spreads, debit card interchange fees, overdraft charges, data-driven marketing, and cross-selling higher-margin products. For consumers, the biggest hidden cost is often opportunity cost: leaving large balances in near-zero-interest checking instead of higher-yield savings. Understanding these mechanics clarifies why banks aggressively compete for checking customers and how to choose accounts that minimize indirect costs.

- Interest spread is the core profit engine: Checking balances typically earn ~0.00%–0.01%, while banks lend those funds at much higher rates, capturing the spread.

- Debit card swipes generate steady revenue: Regulated interchange fees still produce ~$40–$50 per active account annually at scale.

- Overdraft fees remain highly concentrated: A small share of customers generates the majority of overdraft revenue, making “free” accounts costly for frequent overdrafters.

- Your transaction data has economic value: Spending and cash-flow data fuel internal cross-selling and, in aggregated form, broader data monetization.

- The biggest cost may be what you don’t earn: Holding excess cash in checking instead of 4%–5% yield accounts can cost hundreds per year in lost interest.

Your bank calls it “free checking,” and in the most literal sense, it isn’t lying. No monthly maintenance fee appears on your statement. No minimum balance requirement triggers penalties. The marketing promises simplicity, convenience, and zero cost. But free checking accounts are not charitable offerings, they are carefully designed profit centers where banks earn money in ways most customers never notice.

Understanding how banks generate revenue from no-fee accounts reveals a broader ecosystem of income streams that extends well beyond traditional service charges. For consumers, this insight helps explain why financial institutions compete so aggressively for checking account customers and provides clearer context for making more informed banking decisions.

The Interest Spread: Banking’s Core Business Model

The most fundamental way banks profit from checking accounts is through the interest rate spread. When you deposit money in a checking account, the bank does not leave those funds idle. Deposits are pooled and used to support lending activity, such as mortgages, auto loans, personal loans, and credit cards, at interest rates far higher than what depositors are paid.

At large U.S. banks, standard checking accounts typically pay 0.00% to 0.01% interest. Meanwhile, those same institutions may earn roughly 6%–8% on auto loans, 10%–13% on personal loans, and 18%–25% on credit cards, depending on credit quality and market conditions. The difference between what banks earn on loans and what they pay on deposits, the spread, forms a core source of profitability after accounting for operating costs, reserves, and loan losses.

On a $10,000 checking balance, a depositor earning 0.01% receives about $1 per year in interest. That same $10,000, when deployed across the bank’s loan portfolio, can generate hundreds to well over a thousand dollars annually in gross interest revenue. Even after expenses and defaults, the net spread remains substantial at scale.

Online banks and credit unions often share more of this spread with customers, but 3%–4% rates are typically offered on savings or money market accounts, not standard checking. Interest-bearing checking accounts usually require conditions such as direct deposit or debit activity and still tend to pay less than top savings rates. This gap explains why large banks aggressively compete for checking relationships despite offering minimal yields: balances left in low-interest accounts materially increase profitability through the interest spread.

Payment Processing: The Invisible Revenue Stream

Every time you swipe a debit card at a retail checkout, the bank that issued the card earns an interchange fee paid by the merchant’s bank for processing the transaction. In the United States, most debit card interchange is regulated under the Durbin Amendment, which caps fees for large banks (over $10 billion in assets) at 0.05% of the transaction value plus 21 cents, with a possible additional 1 cent for fraud prevention.

On a customer spending about $2,000 per month via debit card, this structure generates roughly $3–$4 per month, or around $40–$45 annually, in interchange revenue for the issuing bank. While modest at the individual level, these fees scale into significant revenue when multiplied across millions of active accounts. This helps explain why banks promote debit card usage and, in some cases, offer limited cash-back rewards, encouraging higher transaction volume increases total interchange collected.

Credit card interchange fees are substantially higher and typically range from about 1.5% to over 3%, depending on the card network, card type, and merchant category. This higher fee structure is one reason banks aggressively market credit cards to existing checking-account customers and encourage multi-product relationships. Credit cards generate not only interchange revenue but also interest income and fee revenue, making them far more profitable than debit cards.

Beyond interchange, banks earn additional payment-related income through out-of-network ATM fees, foreign transaction fees, wire transfer charges, and certain card-related service fees. Collectively, these ancillary charges generate billions of dollars annually across the banking system, although competition and regulatory scrutiny have led some institutions to reduce or eliminate specific fees over time.

Overdraft Fees: The Controversial Cash Cow

Despite being marketed as “free,” checking accounts generate substantial revenue through overdraft fees when customers spend more than their available balance. While overdraft fee income has declined from approximately $12 billion in 2019 to around $5.8 billion in 2023, it remains a significant profit center for many institutions.

The typical overdraft fee ranges from $27 to $35, and research shows that roughly 9% of account holders generate 79% of total overdraft revenue by overdrawing their accounts more than 10 times annually. For these frequent overdrafters, a “free” checking account can cost hundreds or even thousands of dollars per year, far exceeding what an account with an explicit monthly fee would cost.

Banks defend overdraft fees as compensation for providing a service that covers transactions when customers lack sufficient funds. Critics argue the fees are disproportionate to the actual cost of covering temporary shortfalls and function as high-cost loans with effective annual percentage rates that can exceed 3,000% for small, short-term overdrafts.

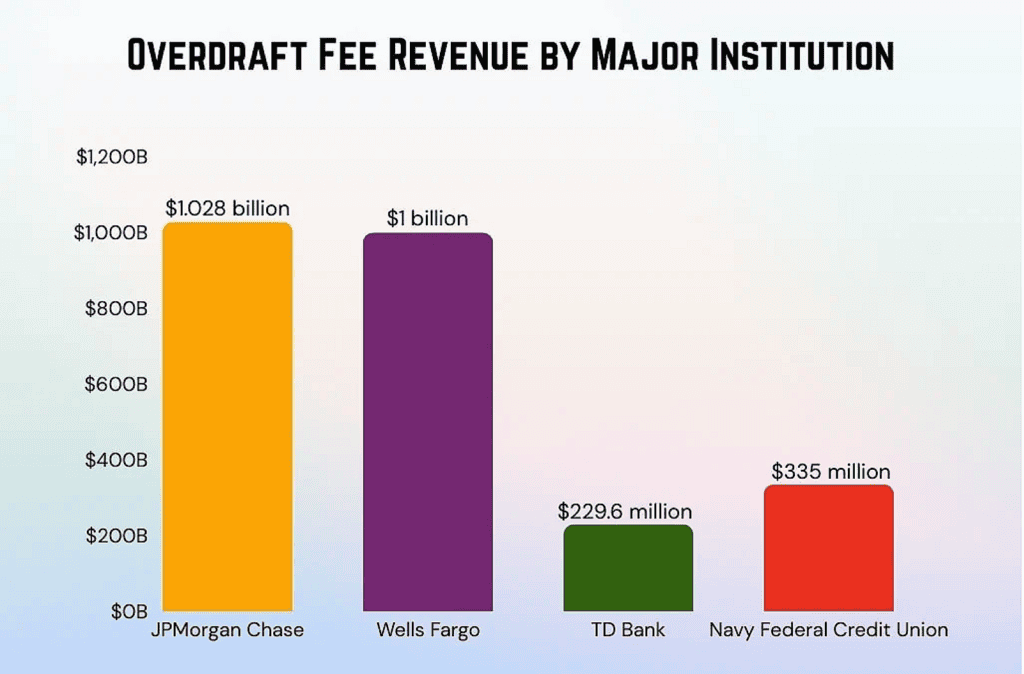

The economics of overdraft protection reveal why banks resist reform despite public pressure. JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo each collected approximately $1 billion in overdraft fees during 2024, representing meaningful contributions to revenue even as their overall deposit bases exceed $1 trillion. Smaller institutions often depend even more heavily on overdraft revenue as a percentage of total income.

Source: CoinLaw

Many banks have voluntarily modified overdraft programs to reduce fees and improve transparency, implementing features like grace periods, low-balance alerts, and minimum overdraw thresholds. Some institutions have eliminated overdraft fees entirely, calculating that the public relations benefit and customer acquisition advantage outweigh the revenue loss. However, the majority of checking accounts still charge substantial overdraft fees, making this “free checking” profit center anything but free for customers who regularly overdraw.

Data Monetization: Your Financial Profile Has Value

One of the least visible but increasingly significant ways banks profit from checking accounts is through data monetization. Your transaction history, spending patterns, income flows, and payment behavior create valuable information that banks analyze and aggregate to improve profitability.

Banks use this data internally to refine marketing for additional products. If your transaction history shows regular payments to a competing credit card company, the bank’s systems may flag you for balance-transfer offers. If you are making rent payments instead of mortgage payments, you may receive home-loan solicitations. Spending and cash-flow data help banks model risk, pre-qualify customers for products, predict future banking needs, and determine which offers to present and at what price. This data does not directly affect traditional credit scores, but it plays a meaningful role in internal decision-making.

External data use is more limited but still economically important. Consumer financial privacy laws restrict the sharing of personally identifiable information, but banks can legally use or share aggregated and anonymized data. This data is valuable to merchants analyzing spending trends, financial firms benchmarking products, and researchers studying consumer behavior. While anonymization is intended to protect privacy, advances in data analytics have blurred the line between anonymous and identifiable data.

Open banking initiatives and data-access frameworks may further shift these dynamics. Third-party payment and financial management apps often request access to banking data through APIs or data aggregators. In some cases, banks receive compensation or indirect economic benefits for providing access; in others, participation is necessary to remain competitive. As a result, a “free” checking account often participates in a data economy that generates revenue beyond what appears on a monthly statement.

Cross-Selling: Checking as the Gateway Product

Banks view checking accounts as loss leaders or break-even products that serve as gateways to more profitable relationships. The real money comes from selling checking account customers additional services: savings accounts, credit cards, mortgages, investment accounts, insurance products, and wealth management services.

The unit economics are straightforward. A basic checking account might generate $50 to $150 annually through interest spreads, interchange fees, and occasional ancillary charges. Add a savings account and that doubles. Add a credit card and the bank might earn $200 to $400 annually from interchange fees and interest charges. Add a mortgage and the lifetime value increases to tens of thousands of dollars from origination fees, interest income, and servicing revenue.

This explains why banks offer sign-up bonuses of $200 to $500 for new checking accounts. These promotions aren’t charitable, they’re customer acquisition costs backed by lifetime value calculations showing that checking account relationships, once established, tend to persist for years and expand over time. The average customer acquisition cost for a checking account ranges from $100 to $300, easily justified if the relationship generates multiple product sales and years of revenue.

Banks track “product per customer” metrics closely, with compensation structures incentivizing branch staff and relationship managers to deepen customer relationships. The pitch is always framed around customer benefit, consolidating banking simplifies financial management, relationship status unlocks rewards, package pricing reduces costs. The underlying reality is that each additional product increases switching costs, reduces price sensitivity, and generates incremental revenue for the bank.

The Opportunity Cost You Pay

The hidden cost of free checking extends beyond what the bank earns to what you lose through opportunity cost. At many large banks, checking account balances still earn around 0.01% interest, while high-yield savings accounts and money market funds have offered roughly 4% to 5% in recent rate environments. The difference represents foregone earnings rather than an explicit fee. On a $10,000 checking balance, this gap translates into approximately $400 to $500 per year in lost interest income, depending on prevailing rates.

Banks benefit when customers maintain higher checking balances than are necessary for day-to-day transactions. Marketing emphasizes safety, convenience, and immediate access, valid considerations, but often downplays the financial reality that many households could shift excess balances into higher-yield accounts without materially sacrificing convenience, particularly given the speed and ease of modern electronic transfers.

A common optimization strategy is to keep only enough money in checking to cover near-term expenses and any minimum balance requirements tied to fee waivers or rewards, while holding the bulk of liquid savings in accounts that pay competitive interest. This approach reduces opportunity cost and improves returns, though it requires more active cash-flow management than the default practice of leaving large balances idle in checking accounts.

The Real Price of Free

Free checking isn’t truly free, it’s a pricing model where costs are indirect rather than explicit. Customers often pay through interest rate spreads, opportunity costs, occasional overdrafts, data use, and cross-selling pressure. Banks profit from these revenue streams while marketing the account as no-cost.

This does not make checking accounts inherently harmful or banks fundamentally deceptive. Modern banking requires revenue to function, and diversified income streams can be less exclusionary than high monthly fees that would otherwise limit access for lower-income households. The growth of genuinely free checking, no monthly fees, no minimum balances, and more consumer-friendly overdraft policies, reflects meaningful progress in financial access.

Understanding the economics explains why some free checking accounts deliver more value than others. Online banks with lower overhead can offer higher interest rates and fewer fees because their cost structures allow it. Credit unions often return more value to members due to their cooperative, nonprofit model. Large banks typically design free checking to support profitability across multiple products.

The best free checking account aligns with how you actually bank. High-balance customers using multiple products may benefit from relationship programs despite low interest rates. Those with minimal balances often benefit more from online banks offering higher yields and fewer fees. Frequent overdrafters are best served by accounts that cap or eliminate overdraft charges, which can reduce annual costs significantly.

The common thread is awareness. Knowing how banks earn money from your account enables better decisions about where to bank and how to structure your finances. Free checking exists because it is profitable for banks. Ensuring the trade works in your favor requires understanding what you give up for that “free” account.

This topic is part of the broader banking system. For a complete explanation of accounts, transfers, fees, and consumer protections, see our Banking & Cash Management guide.