Open Banking Security Risks: Data Exposure, Fraud, and How to Stay Safe

15.7 min read

Updated: Dec 26, 2025 - 17:12:52

Open banking replaces risky practices like credential sharing with regulated APIs, explicit user consent, and standardized security controls, making it materially safer than screen scraping. However, it is not risk-free. By expanding data access beyond banks to authorized third parties, open banking increases the attack surface, introduces third-party security dependencies, and raises privacy and data-use concerns. The real risk to consumers depends less on the open banking model itself and more on which providers are used, what permissions are granted, and how actively access is monitored and revoked.

- Security improves, but complexity increases: API-based access with time-limited consent is safer than sharing login credentials, but more parties and integrations mean more potential failure points.

- Third-party risk is the biggest variable: Authorized fintechs can access sensitive financial data; their security maturity and data-handling practices matter as much as the bank’s.

- Privacy risk persists even without breaches: Lawful data use, aggregation, and long retention periods can expose users to unintended secondary uses of their financial information.

- User behavior materially affects outcomes: Limiting permissions, revoking unused access, avoiding phishing, and securing devices significantly reduces real-world risk.

- Compared to legacy alternatives, open banking is safer: When used thoughtfully, regulated open banking frameworks offer stronger controls than screen scraping or manual data sharing.

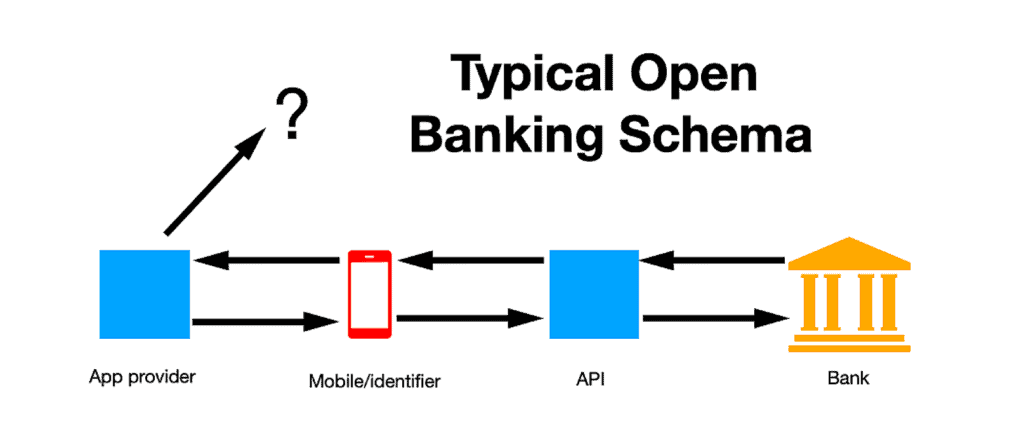

Open banking introduces a fundamentally different architecture for financial data access, one that is widely considered more secure than legacy practices such as screen scraping. Instead of requiring users to share bank login credentials, open banking relies on regulated APIs, explicit user consent, and standardized security controls.

However, “more secure than the alternatives” does not mean “risk-free.” Open banking still introduces security and privacy considerations related to third-party access, data handling, and authorization scope. Understanding these specific risks, and the safeguards designed to mitigate them, helps consumers make informed decisions about which services to trust and how to use them safely.

The Expanded Attack Surface

Traditional banking concentrated most security concerns within a relatively contained environment. Customer financial data resided primarily on a bank’s own systems and was protected by that institution’s internal security controls. Access was typically mediated through the bank’s authentication mechanisms, meaning responsibility for safeguarding credentials and monitoring access rested largely with a single organization.

Open banking deliberately expands this model. With customer consent, financial data is accessed and transmitted through standardized Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) to authorized third-party providers. While banks continue to hold the underlying account data, third parties may temporarily process, cache, or store portions of that data on their own systems, depending on their service model and regulatory permissions. As a result, security responsibility is distributed across multiple organizations, each with its own controls, practices, and risk management maturity.

This broader ecosystem increases the number of potential entry points for attackers. Each API endpoint, authentication exchange, token issuance process, and third-party system represents a potential attack surface. A single user action such as initiating a payment or retrieving account information, can involve numerous API interactions across banks, intermediaries, and service providers.

Source: SecurityWeek

The cumulative effect of these interactions, combined with the number of participating entities and integration points, creates a materially larger and more complex attack surface than traditional closed banking systems. While this expansion enables innovation, competition, and consumer choice, it also introduces greater systemic complexity and a higher number of potential vulnerability points that must be actively managed.

Third-Party Vulnerabilities

Your bank is a heavily regulated institution subject to extensive security requirements, regular audits, and ongoing regulatory oversight. Third-party providers accessing your data through open banking are also regulated in many jurisdictions, but the nature and extent of those requirements vary considerably depending on the country, license type, and regulatory framework.

Not all third parties have the same security maturity as established financial institutions. Fintech startups may be innovative and user-friendly but often lack the deep security resources, staffing, and institutional experience of organizations that have been managing financial data security for decades. This variance can create potential weak points in the broader open banking ecosystem.

Data breaches affecting third-party services can expose the financial information those services collect through open banking. While API-based access means these providers do not store your online banking credentials, they do hold the data you authorize them to access, including transaction histories, balances, and account details. In 2024, the average cost of a data breach in the global financial sector reached $6.08 million, the highest of any industry.

The practical risk depends heavily on which third-party services you use. Large, established fintech companies with substantial security teams and resources generally present different risk profiles than smaller startups with limited security budgets. This is not to suggest that size alone determines security quality, small companies can implement strong security controls, and large organizations can still suffer breaches, but resource availability typically correlates with greater investment in security.

Phishing and Social Engineering Attacks

The collaborative nature of open banking creates new opportunities for social engineering. Fraudsters can exploit the complexity of the ecosystem to deceive users into authorizing access they did not intend to grant.

Phishing attacks may impersonate legitimate open banking services, redirecting users to fake websites that closely mimic their bank’s real authentication pages. Users who believe they are authorizing a genuine service may instead approve a fraudulent request or be tricked into entering credentials on a counterfeit banking site, enabling attackers to collect data or prepare more targeted fraud attempts.

The redirection flows inherent in open banking authentication, where users are sent from a third-party app to their bank and back, can be confusing and increase the risk of deception. Users who are unfamiliar with how regulated open banking consent flows work may fail to recognize when a redirection leads to a fraudulent domain rather than their bank’s legitimate website.

Impersonation represents another significant vector. Criminals may pose as legitimate third-party providers or as banks themselves, contacting users to request authorization or to “verify” or “renew” existing consents. These social engineering attacks exploit the fact that open banking relies on explicit user authorization, making such requests appear plausible even when they are fraudulent.

Third-party providers with weaker fraud awareness or customer education may be more susceptible to being abused in these schemes. While regulated providers are subject to baseline security requirements, attackers tend to target the least mature participants in an ecosystem, knowing that user confusion and inconsistent defenses can create opportunities for exploitation.

Account Takeover Risks

If a malicious actor gains access to the mobile device or login credentials you use with an open banking service, they could potentially take control of that service’s authorized access to your financial accounts. While they still cannot log directly into your bank’s online banking interface without your banking credentials, they may be able to interact with your bank through the third party’s authorized API access for malicious purposes.

This risk is partially mitigated by the limited nature of many open banking permissions. Read-only access does not allow funds to be moved, only viewed. Time-limited consents mean access does not persist indefinitely, and revocation mechanisms allow you to terminate access if you suspect compromise.

However, the risk is not zero. An attacker with access to read-only financial data can analyze transaction histories, income timing, spending behavior, and account relationships, enabling more targeted social engineering, identity fraud, or follow-on attacks.

For services with payment initiation capabilities, the risk increases. While payments generally require explicit authorization under strong customer authentication rules, some consents may permit recurring or pre-authorized transactions. If an attacker controls the device or account used to approve payments, they may be able to initiate fraudulent transfers. Strong customer authentication, requiring multiple independent factors, provides protection, but device compromise can significantly weaken these safeguards.

Data Misuse and Privacy Violations

Even when security controls successfully prevent unauthorized access, concerns remain about how authorized parties use the data they legitimately obtain. Third-party services may process financial data in ways users did not anticipate or might not approve if the implications were fully understood at the time of consent.

Some services aggregate and analyze data across large user bases to generate insights that may be monetized or shared with partners. While individual records are often anonymized or pseudonymized, aggregated patterns and behavioral trends derived from financial data retain significant commercial value. As a result, your data may contribute to products or analyses you were unaware of and from which you receive no direct benefit.

Open banking regulations impose purpose-limitation requirements intended to restrict data use to the specific purposes authorized by the user. However, enforcement can be difficult in practice, and determining whether a particular use aligns with an approved purpose often involves interpretation rather than clear technical boundaries.

Data retention introduces related risks. Third parties vary widely in how long they store collected financial data. Some delete it after fulfilling the authorized service, while others retain detailed historical records for extended periods. Longer retention increases exposure if the service experiences a breach or if retained data is later repurposed in ways the user did not anticipate.

Although regulations such as GDPR provide safeguards, including rights to access and request deletion, the practical reality is that authorizing data access inherently reduces direct user control. Understanding how services manage data usage, aggregation, and retention is essential when deciding which providers to trust with sensitive financial information.

API-Specific Security Concerns

The API-based architecture that enables open banking also introduces distinct technical security considerations. APIs can contain vulnerabilities, such as implementation bugs, configuration errors, or weak authorization controls, that attackers may exploit to gain unauthorized access to data or functionality.

Securing APIs requires disciplined implementation. Measures such as strong authentication and authorization mechanisms, encryption of data in transit and at rest, rate limiting to prevent abuse, rigorous input validation, and regular security testing all contribute to effective API security. However, the consistency and maturity of these controls can vary across institutions and service providers.

Ongoing changes to APIs present additional risk. When banks or third parties update APIs to add features, optimize performance, or resolve defects, those changes can inadvertently introduce new vulnerabilities or temporary security gaps. While structured testing and change-management processes reduce this risk, the fast development cycles common in fintech environments increase the frequency of such updates.

Open banking transactions also rely on interconnected API calls across multiple systems. This interdependence creates shared risk: a weakness in any single component or integration point can affect the security of the overall transaction flow. Maintaining strong security therefore requires continuous oversight of every API endpoint, dependency, and connection involved.

The Regulatory Safety Net

Understanding open banking risks also requires understanding the protective measures regulators have put in place. In jurisdictions where open banking is formally regulated, such as the EU and UK, regulatory frameworks establish minimum security standards and consumer protections designed to address known vulnerabilities.

Strong Customer Authentication (SCA) requirements under regulations like PSD2 mandate multi-factor authentication for most account access and electronic payment authorizations. SCA requires at least two of three elements: something you know (such as a password), something you have (such as a mobile device), and something you are (such as a fingerprint). While certain low-risk or low-value transactions may qualify for exemptions, SCA significantly reduces the risk of unauthorized access compared to single-factor authentication.

Encryption requirements protect data transmitted between parties from interception. Open banking APIs rely on Transport Layer Security (TLS) to encrypt data in transit, making intercepted communications unreadable to unauthorized actors. Many providers also encrypt sensitive data at rest as part of broader security and compliance obligations.

Data minimization principles, primarily enforced through data protection laws such as GDPR, limit how much information third parties may access. Providers are expected to request only the data necessary for their stated purpose, reducing exposure if a breach occurs or access is misused.

Consent management requirements ensure users understand what they are authorizing and can withdraw consent. In regulated open banking frameworks, access permissions are typically time-limited and must be actively renewed, preventing indefinite access to financial data if users stop using a service.

Regulatory oversight of third-party providers includes authorization or registration requirements and ongoing supervision. Authorized providers must demonstrate compliance with security, governance, and operational standards, and regulators can investigate complaints, conduct audits, and revoke authorization for non-compliance.

Consumer liability protections limit financial losses from unauthorized transactions, provided issues are reported promptly. The specific liability caps and dispute rules vary by jurisdiction, but regulated frameworks generally place the bulk of financial responsibility on banks and payment providers rather than consumers acting in good faith.

Practical Steps to Minimize Risk

While regulatory frameworks provide baseline protections, individual users can take additional steps to minimize their exposure to open banking security risks.

Use services from reputable, established providers with track records of security competence. Check whether providers are properly authorized in relevant registries. In the UK, the regulated providers registry lists authorized open banking service providers. Verified registration doesn’t guarantee perfect security but indicates the provider has met regulatory standards.

Limit the scope of permissions you grant. Connect only the accounts actually necessary for a service to function. Authorize access only for the data types the service genuinely needs. If a budgeting app requests payment initiation capabilities but you only want read-only access, question whether you need that particular service or whether alternatives exist that request more limited permissions.

Regularly review and revoke unused authorizations. Don’t let dormant connections accumulate. If you stop using a service, revoke its access immediately rather than letting permissions persist until automatic expiration.

Enable all available security features on devices you use for banking and open banking services. Use biometric authentication where available. Keep devices and apps updated to receive security patches. Use strong, unique passwords for financial services and consider a password manager to maintain them securely.

Be skeptical of communications claiming to be from banks or financial services. Don’t click links in emails or messages asking you to authorize or reauthorize open banking access. Instead, navigate directly to the legitimate service or your bank’s website. Verify requests through independent channels before taking action.

Monitor your accounts regularly for unexpected transactions or access. Many banks provide notifications for account access or transactions above certain thresholds. Enable these alerts so you’re quickly aware of potentially unauthorized activity.

Understand what you’re authorizing before confirming. Read consent screens carefully. If something seems unclear or if requested permissions seem excessive for the stated purpose, seek clarification or decline authorization until you understand what you’re agreeing to.

Distinguishing Real Risk from Theoretical Risk

Discussions of security risks can sometimes drift into listing every conceivable threat, creating the impression that open banking is inherently dangerous. Context matters when assessing actual risk.

Many of the security concerns associated with open banking exist in any system that involves sharing sensitive data across multiple organizations. Online shopping, for example, requires consumers to trust merchants and payment processors to handle financial information securely, while social media platforms collect and monetize personal data under far less sector-specific regulatory oversight than financial data-sharing frameworks.

The appropriate comparison is not a hypothetical perfectly secure system, but the real alternatives that existed before open banking. Screen scraping, the practice open banking was designed to replace, required users to share full banking credentials with third parties, creating significantly greater security exposure than token-based API access. Manual data sharing, such as emailing spreadsheets or photographing bank statements, also carries substantial privacy and security risks.

Open banking’s regulatory frameworks, standardized authorization flows, explicit consent, and revocation capabilities make it comparatively more secure than many informal or legacy methods of achieving similar outcomes. This does not eliminate risk, but it does mean those risks are formally recognized, constrained through technical and regulatory controls, and generally more manageable than in unregulated or ad-hoc data-sharing arrangements.

The Ongoing Evolution of Security

Security in open banking isn’t static. As the ecosystem matures, both threats and protective measures evolve. Attackers develop new techniques; defenders respond with enhanced security controls.

Transaction risk analysis represents one advanced security measure. These sophisticated systems assess each transaction in real time, scrutinizing variables like amount, parties involved, device used, and historical patterns. When risk levels are identified as low, the system might simplify authentication requirements, balancing user experience with security. For high-risk transactions, additional authentication measures activate, strengthening protections when they’re most needed.

Machine learning increasingly supports fraud detection, analyzing patterns across thousands of transactions to identify anomalies that might indicate fraud or compromise. These systems can detect subtle indicators that human reviewers might miss while processing information at scale.

Behavioral analytics add another layer, building profiles of normal user behavior and flagging deviations that might indicate account takeover or unauthorized access. If your typical pattern is small, regular transactions and suddenly large, unusual payments begin appearing, the system can challenge those transactions or temporarily restrict access pending verification.

The distributed nature of open banking means security improvements benefit from network effects. When one institution develops effective fraud detection approaches, those methods can spread across the ecosystem. Security standards evolve based on emerging threats and proven protective measures.

Making Informed Tradeoffs

Perfect security does not exist in any system that involves digital access and data sharing. The relevant question is not whether open banking carries risk, it does, but whether those risks are acceptable in light of the benefits and compared to the available alternatives.

For many users and use cases, the convenience and functionality of open banking services outweigh the security considerations. The ability to view multiple accounts in one place, receive tailored financial insights, or streamline payments can provide sufficient value to justify the calculated risk of sharing data with authorized and regulated third-party providers.

For others, particularly those with heightened security concerns or strong privacy preferences, the tradeoffs may favor more conservative approaches. Relying solely on services offered by a primary bank, manually consolidating financial information, or choosing to forgo certain features altogether can be reasonable decisions based on individual risk tolerance.

The key is making these choices consciously, with a clear understanding of the actual risks, the protections in place, and the steps available to reduce exposure. Open banking security is less about whether to participate and more about how to participate thoughtfully, selecting reputable providers, granting only necessary permissions, regularly reviewing and revoking access, and staying aware of how financial data is used.

Security in open banking is a shared responsibility. Regulators define frameworks and minimum standards. Banks implement secure APIs and authentication mechanisms. Third-party providers are responsible for building secure applications and handling data appropriately. Users, in turn, make informed authorization decisions, monitor connected services, and act when concerns arise. When these elements work together, open banking can deliver meaningful benefits while keeping risk at a level that is imperfect, as all security is, but sufficiently robust to support trusted financial data sharing.