Why You Can’t Pay Off Your Loans Early — Even When You Want To

9.6 min read

Updated: Dec 26, 2025 - 06:12:44

Paying off a loan early may feel like the responsible choice, but hidden prepayment penalties can turn that move into an expensive mistake. Lenders often charge these fees, typically 1–5% of the remaining balance, to recover lost interest income. While reforms under the Dodd-Frank Act have limited mortgage penalties, they still appear in auto, personal, and business loans, where regulation is lighter. The key to avoiding surprise costs is understanding your contract before signing or refinancing.

- Prepayment penalties remain legal in many U.S. loan types, especially auto, personal, and small business financing, despite tighter mortgage rules from the CFPB.

- Typical charges range from several months’ interest to 5% of the outstanding balance, often wiping out savings from early payoff.

- Auto loans using the “Rule of 78s” frontload interest, meaning early payoff saves little, if anything, on total cost.

- Federal student loans have no prepayment penalties, but some private student or commercial loans include disguised “administrative” fees.

- Before paying early or refinancing, ask your lender to confirm in writing whether your loan includes any prepayment, early termination, or yield maintenance fees.

Paying off a loan early often seems like the ultimate act of financial discipline, a smart move that should save you thousands in interest and provide peace of mind. But for many borrowers, that’s not always the case. Instead, some are penalized for doing what seems like the right thing.

Hidden within the fine print of certain mortgages, auto loans, business financing agreements, and even personal credit contracts are prepayment penalties, fees lenders charge when loans are repaid ahead of schedule. These penalties exist to protect a lender’s expected interest income and discourage early repayment.

While these clauses are legal and must be disclosed under federal lending laws, many borrowers overlook them until they attempt to refinance or pay off a balance early. Prepayment clauses are less common today due to tighter regulation but still appear in some conventional and auto loans.

Although there isn’t a precise national figure, experts agree that such fees collectively cost borrowers significant sums each year. The bottom line: paying early doesn’t always guarantee savings, and understanding your loan terms before signing can help you avoid costly surprises.

The Paradox of Paying Early

The logic behind a prepayment penalty is simple: when you repay a loan early, the lender loses the future interest income it expected. To recover that loss, many charge a fee, typically between 1% and 5% of the remaining balance, or the equivalent of several months’ interest. That means paying off debt faster doesn’t always lead to financial freedom. In some cases, it triggers an added cost instead.

According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, prepayment penalties have become less common in mortgages thanks to federal reforms under the Dodd-Frank Act and the Qualified Mortgage Rule, which tightly limit when and how they can apply. However, these fees still appear in other lending sectors, particularly auto loans, personal loans, and small business financing, where regulation is lighter and disclosure less consistent. In short, while early repayment sounds like a smart move, borrowers should always read the fine print first.

Why Lenders Impose Penalties

Banks and finance companies earn profit primarily through interest payments spread over the life of a loan. When borrowers repay early, that predictable stream of income disappears. Prepayment penalties are designed to offset this loss and protect lenders from reinvestment risk, the challenge of lending the repaid funds again at a lower rate.

A typical clause might state that the borrower owes “the greater of three months’ interest or the interest rate differential” if the loan is paid off ahead of schedule. On a $400,000 mortgage at around 5% interest, that could equal roughly $5,000 to $10,000. For smaller loans such as auto or personal credit, the penalty may be lower, often a few hundred dollars or a percentage of the remaining balance.

Lenders argue these penalties cover administrative costs and compensate for lost interest income. Critics, however, see them as a double charge: borrowers pay to use the money, and then pay again to stop borrowing it. Regulations in some markets limit or ban prepayment fees, but they remain common in many private and commercial loan contracts.

Mortgages: The Most Punitive Example

The mortgage market has long been the harshest when it comes to prepayment penalties. Fixed-rate home loans often carry steep break fees, especially when interest rates fall and borrowers try to refinance.

In countries like Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, homeowners who lock in a low fixed rate and later refinance can face penalties reaching tens of thousands of dollars. In Canada, the charge is often calculated using an interest rate differential formula, while in the UK it typically takes the form of a 1–5% early repayment charge on the outstanding balance.

Even in the United States, where the Dodd-Frank Act limited such clauses, prepayment penalties remain legal for certain short-term or high-cost loans.

Mortgage specialists often refer to this as the “interest rate differential trap.” When market rates drop, lenders recalculate the interest they’ll lose over the remaining term, producing break fees so large they erase the savings from refinancing.

For lenders, these charges hedge against rate volatility. For borrowers, they act as a hidden anchor, locking households into uncompetitive loans long after better deals appear.

Auto Loans: The Silent Offender

Auto loans are another area where early repayment can backfire, not always through explicit penalties, but through the way interest is structured.

Some car loans still use what’s known as the Rule of 78s, or precomputed interest, a method that frontloads most of the interest payments into the early months of the loan. Even if you pay off halfway through, you’ve likely already covered most of the total interest cost. Although this formula has been restricted for longer loans in several U.S. states, it still appears in certain short-term or subprime financing contracts.

In practical terms, this means borrowers who settle early may save far less than they expect. A 60-month loan paid off after two years could have already accumulated the bulk of its interest under such a schedule.

According to Experian’s State of the Automotive Finance Market, the average new-car loan in the U.S. now exceeds $41,000. Average interest rates hover around 6.7% for new vehicles and rise above 11% for used ones. For lenders, that structure ensures predictable profits. For consumers, it’s a reminder that paying early doesn’t always mean saving money.

Personal and Small Business Loans

Prepayment penalties also appear in unsecured personal loans and small business financing, areas that often operate under lighter regulatory oversight.

Online lenders, peer-to-peer platforms, and smaller finance companies may include early termination fees or prepayment charges in their contracts, typically ranging from a flat fee to several months’ worth of interest. According to Experian, these clauses can erode or eliminate the benefits of paying off debt early.

In commercial and private credit markets, make-whole provisions and call-protection clauses are increasingly common. These require borrowers to compensate lenders for the interest they would have earned if the loan had run to maturity. Legal analyses from Sidley Austin and Proskauer confirm that such provisions are widespread in private credit deals, designed to preserve predictable investor cash flows.

The Bank for International Settlements notes that the rapid expansion of private credit markets has been driven partly by investor demand for stable returns, encouraging the growth of strict prepayment protections that can make refinancing prohibitively costly in some cases.

Student Loans and Other Consumer Credit

Federal student loans in the U.S. do not include prepayment penalties. Borrowers can pay off their loans early at any time without extra charges, according to the U.S. Department of Education. However, some private student loans may include early repayment disincentives through “administrative” or “processing” fees, or by using precomputed interest structures that prevent a full reduction in total interest when paid off early.

In other forms of consumer credit, such as credit cards, buy-now-pay-later plans, and retail installment financing, “deferred interest” offers can have similar effects. If the balance is not paid in full by the promotional deadline, or if a payment is missed, lenders can retroactively apply all accrued interest from the start of the term. Many borrowers believe they are avoiding interest, only to find that the fine print allows lenders to charge backdated interest once the promotion expires.

How Regulators Have Responded

Regulators have made uneven progress in tackling prepayment penalties.

- In the United States, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau limits mortgage prepayment penalties to the first three years of certain fixed-rate loans and bans them on adjustable-rate and high-cost mortgages.

- In the European Union, the Consumer Credit Directive allows lenders to charge only “fair compensation” for proven losses.

- Australia and New Zealand permit break fees but require that they reflect actual costs.

Despite these protections, enforcement is weak. Most penalties remain legal, and many borrowers sign contracts without understanding the implications. Consumer groups argue that these charges distort competition by discouraging refinancing when rates improve.

Who Really Pays the Price

At a systemic level, prepayment penalties shift power from borrowers to lenders. They lock people into loans that may no longer make sense, preventing refinancing, consolidation, or early payoff strategies. The result is less financial flexibility and greater profit certainty for lenders.

Studies by institutions such as the World Bank confirm that excessive prepayment penalties restrict consumer choice and protect lenders’ returns by discouraging early repayment. Research on mortgage markets also shows that higher penalties significantly reduce borrowers’ ability to refinance when interest rates fall, effectively trapping them in costlier loans.

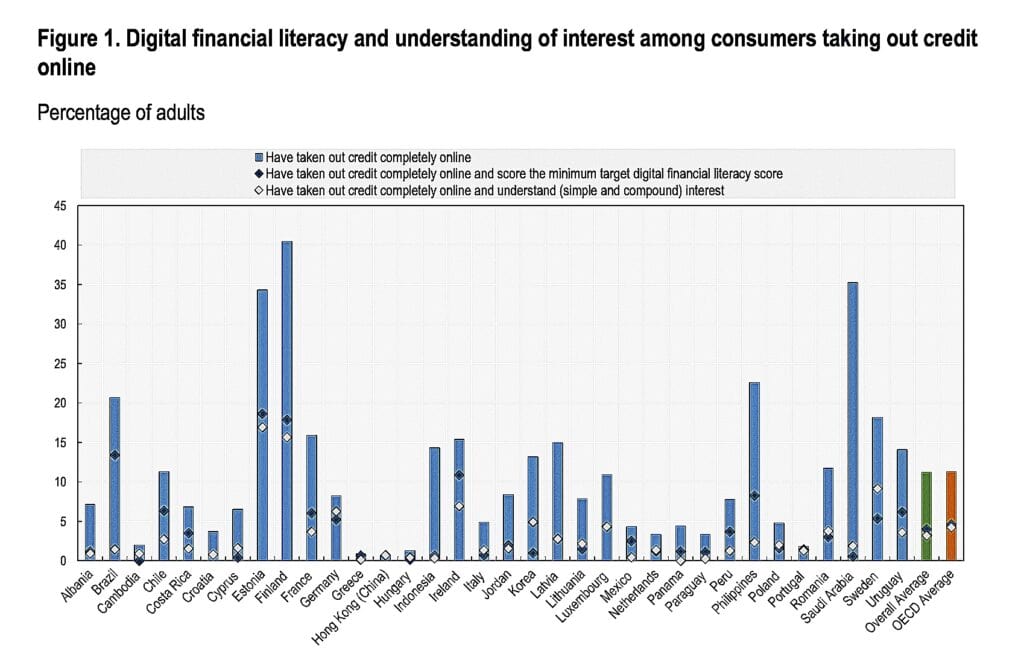

According to the OECD, many borrowers remain unaware of key borrowing costs, including repayment charges and hidden fees, before signing loan contracts. Limited transparency erodes potential savings, reduces refinancing benefits, and punishes financially responsible borrowers who try to pay off their debts early.

Source: OECD

How to Protect Yourself

The best defense is vigilance before you sign. Borrowers should:

- Ask directly if the loan includes a prepayment penalty or early settlement fee.

- Request written confirmation of how interest is calculated and whether it’s precomputed or simple interest.

- Compare variable and fixed-rate options, as variable loans often allow greater flexibility for early repayment.

- Use online loan calculators to estimate break costs before refinancing or paying off a loan early.

- Keep documentation of all lender promises and contract terms.

If you already have a loan, review your contract for terms like “early termination fee,” “yield maintenance,” or “Rule of 78s.” These signal that early repayment could cost you.

The Bottom Line

The right to repay debt early should be a basic financial freedom, not a privilege controlled by lenders. Yet across mortgages, auto loans, and personal credit, millions remain locked into contracts that punish responsible behavior.

Despite regulatory limits from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in the U.S. and “fair compensation” standards under the EU Consumer Credit Directive, prepayment penalties persist in many markets. Weak enforcement and vague disclosures leave borrowers unaware of their true costs until it’s too late.

Prepayment penalties are the quiet enforcers of lender profit, legal, opaque, and deeply embedded in loan structures. Until regulators enforce full transparency and fairness, the best protection remains awareness. In lending, the fine print often decides whether financial freedom truly belongs to the borrower, or the bank.

Related: This topic is part of the broader credit system. For an overview of how credit scores, loans, and debt work together, see our Credit & Debt guide.