Why Federal Student Loans Don’t Cover College Costs: Understanding the Gap

8.8 min read

Updated: Dec 26, 2025 - 06:12:52

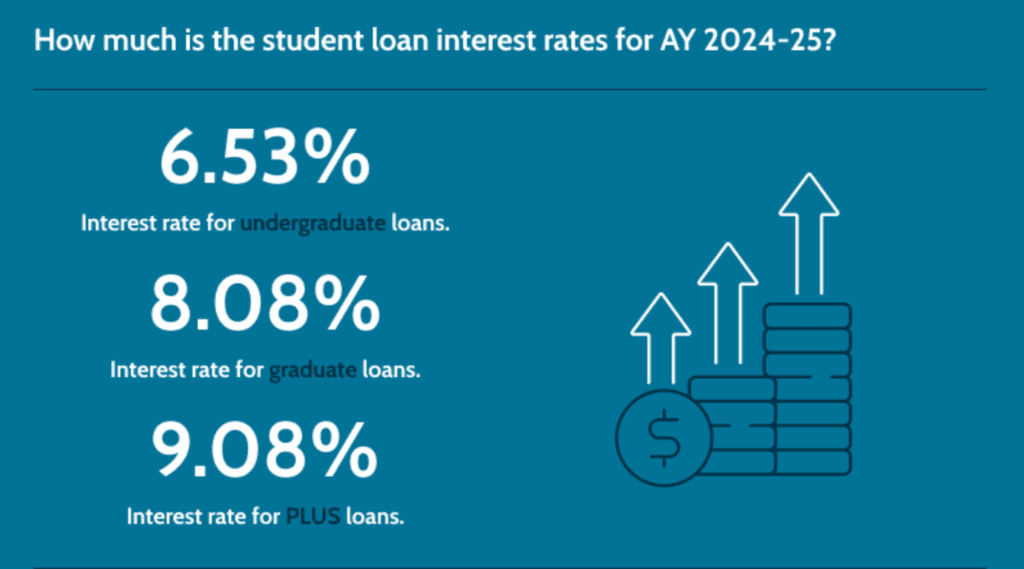

For 2024–2025, federal student loan limits for undergraduates remain stuck at early-2000s levels, while college costs have more than doubled. The result: most students can borrow only about one-third of what a four-year degree actually costs. New 2026 borrowing caps on Parent PLUS and graduate loans will make that gap even larger, forcing many families toward higher-interest private loans. Understanding these limits is crucial for choosing affordable schools, maximizing aid, and avoiding long-term debt traps.

- Federal loan limits are outdated: Dependent undergraduates can borrow up to $31,000 total, though average in-state college costs exceed $27,000 per year.

- Costs outpace aid by 3-to-1: The average public university degree costs roughly $108,000; federal loans cover only $31,000, leaving a $77,000 gap.

- 2026 rules shrink borrowing options: Grad PLUS and Parent PLUS programs will face strict lifetime caps, $100,000 for graduate students, $65,000 per child for parents.

- Private loans fill the gap – but at a cost: They carry variable rates, limited repayment protections, and credit requirements that federal loans avoid.

- Plan strategically: Choose lower-cost schools, pursue scholarships and grants aggressively, and understand that federal aid alone won’t cover full expenses under current law.

If you’re planning to pay for college with federal student loans, you’re about to discover a harsh reality: the money you can borrow from the government won’t come close to covering your actual costs. This isn’t a bug in the system – it’s a feature that leaves millions of families scrambling to fill a gap that can reach tens of thousands of dollars per year.

The Numbers Don’t Add Up

Here’s the fundamental problem: federal student loan limits were set decades ago and haven’t kept pace with the explosive growth in college costs.

What you can borrow as a dependent undergraduate:

Freshman year: $5,500

Sophomore year: $6,500

Junior year and beyond: $7,500 per year

Lifetime maximum: $31,000

According to the Federal Student Aid Handbook (2024–25), these limits haven’t changed significantly in decades, even as tuition and living expenses have soared.

What college actually costs (2024–2025 averages):

In-state public university: $27,146 per year

Out-of-state public university: $45,708 per year

Private university: $58,628 per year

Data from the Education Data Initiative show that the average annual cost of attendance, including tuition, fees, housing, and other expenses, has reached record highs.

Do the math on a four-year degree at an in-state public school. Total cost: approximately $108,584. Maximum federal loans you can take: $31,000. That leaves a gap of roughly $77,000 that you’ll need to cover through savings, scholarships, work, or private loans.

Why the Limits Are So Low

Federal student loan limits aren’t arbitrary numbers pulled from thin air. They were established by Congress through legislation, most notably the Higher Education Act of 1965, and were designed with specific policy goals in mind.

The original intent was protection and access. Lawmakers wanted to make higher education attainable without saddling students with unmanageable debt. By capping how much students could borrow, Congress sought to expand access to college while preventing young people from taking on more debt than they could reasonably repay with entry-level salaries.

The problem: costs rose, limits didn’t. When current loan limits were largely set in the early 2000s, college was significantly cheaper. The last major increase came in 2008, when Congress passed the Ensuring Continued Access to Student Loans Act, raising undergraduate annual limits by $2,000. Since then, the caps have remained frozen while tuition and fees have more than doubled. According to the Urban Institute and NASFAA, today’s federal limits cover only about one-third of the average cost of attendance at a public university, down from two-thirds in the mid-1990s.

Political inaction has kept limits frozen. Any adjustment would require Congressional approval, and lawmakers remain divided over whether higher borrowing caps would help students or simply allow colleges to raise prices further. This ongoing debate has left the system stuck: college costs keep climbing, but federal borrowing power hasn’t budged in nearly two decades.

The Reality for Different Student Types

Not all students face the same borrowing limits, and understanding these distinctions is crucial:

- Dependent undergraduate students (those whose parents claim them on tax returns and are expected to contribute to college costs) face the strictest limits: $31,000 over their entire undergraduate career. The Department of Education assumes parents will help pay the difference.

- Independent undergraduate students (typically age 24+, married, veterans, or those with dependents of their own) can borrow more: up to $57,500 total, with higher annual limits of $9,500 to $12,500. This recognizes they don’t have parental support but still leaves a large gap.

- Graduate and professional students could previously borrow up to $138,500 in federal loans (including undergraduate borrowing). However, new limits taking effect in 2026 cap most graduate borrowing at $100,000 total – a change that will force many graduate students toward private loans.

How Families Fill the Gap

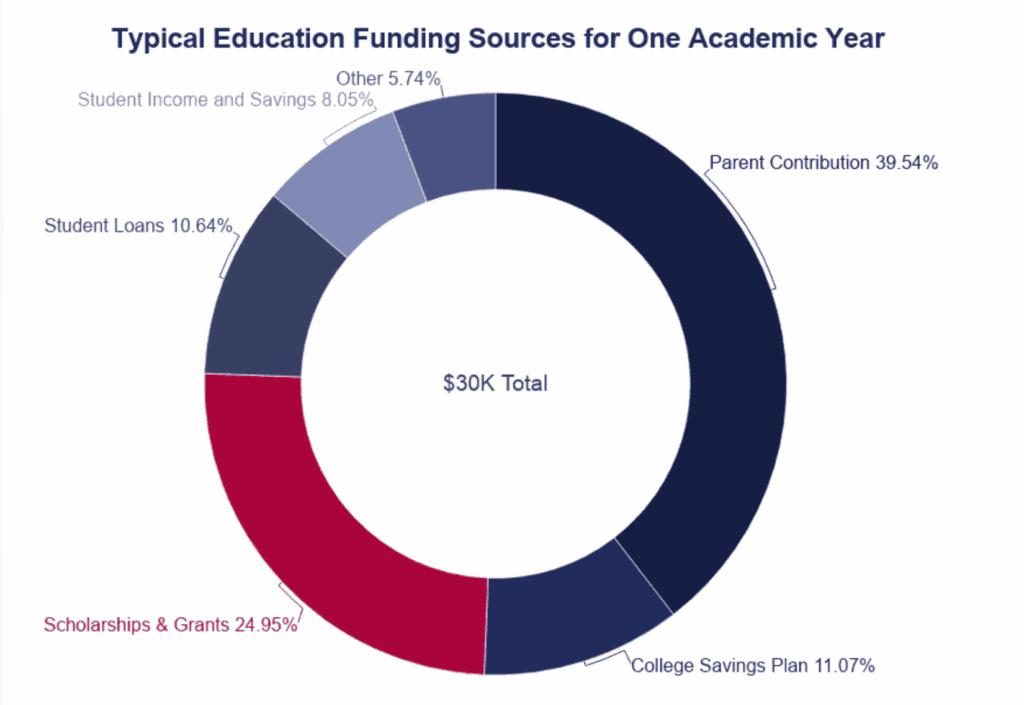

Since federal student loans don’t cover the full cost of attendance, families rely on a patchwork of strategies to fill the gap. Parent PLUS Loans allow parents of dependent undergraduates to borrow up to the full cost of attendance minus other financial aid. These federal loans carry higher interest rates than student loans (8.94% for 2025-26 per the U.S. Department of Education) and require a credit check for adverse history.

Source: Research.com

Beginning July 1, 2026, new rules will cap Parent PLUS borrowing at $20,000 per year and $65,000 total per child, replacing the current “borrow-up-to-cost” policy and closing another major avenue for covering college expenses.

Private student loans from banks and fintech lenders fill the remaining gap for many families. Unlike federal loans, these typically require good credit or a cosigner, offer far fewer repayment protections, and charge variable interest rates based on creditworthiness rather than fixed federal terms.

Work and savings contribute what they can, but campus and summer jobs rarely make a serious dent in five-figure annual costs. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports average part-time student earnings around $6,000 per year, barely a fraction of typical tuition and living expenses.

Scholarships and grants ease the burden for some, but the average scholarship covers only about 25% of annual college costs, according to Education Data Initiative. Merit aid frequently flows to top academic performers rather than those with the greatest financial need.

Source: Education Data

Ultimately, many families go into debt anyway, just private debt instead of federal debt. Home-equity lines of credit and private student loans are common last-resort tools, but they lack the borrower protections and flexible repayment options that federal loans provide.

The 2026 Changes Make Things Worse

Why This System Persists

You might wonder why, if the gap is so obvious and so harmful, Congress hasn’t simply raised the limits. The answer involves competing concerns:

Concerns about enabling price increases: Some policymakers argue that increasing loan limits would simply allow colleges to raise prices further, knowing students can borrow more. Research has found evidence that the availability of federal student aid has contributed to tuition inflation.

Fears of unsustainable debt: Others worry that higher borrowing limits would lead to even more graduates with unmanageable debt, potentially triggering higher default rates and demands for broader loan forgiveness.

Ideological divides: Republicans generally favor limiting government lending and want students to have “skin in the game,” while Democrats worry about access but also face progressive critics who want to reduce reliance on loans altogether in favor of free college and loan forgiveness.

Lack of urgency: Most members of Congress attended college when it was far more affordable. The current crisis doesn’t resonate with their lived experience, reducing political will to act.

What This Means for Your College Decision

Understanding the gap between federal loan limits and actual costs should fundamentally shape how you approach college:

Choose schools strategically. If you’ll rely heavily on loans, the sticker price matters more than prestige. A school where you can graduate with minimal debt may serve you better than a “dream school” that requires six figures in private loans.

Maximize grants and scholarships first. Every dollar you receive in gift aid is a dollar you won’t need to borrow beyond federal limits. Apply widely for scholarships and choose schools where your academic profile makes you eligible for merit aid.

Consider starting at community college. Two years at a community college followed by transfer to a four-year school can cut your total costs dramatically, reducing how much you need to borrow beyond federal limits.

Understand what you’re signing up for. If you’ll need private loans to cover the gap, research those terms carefully. Private loans don’t offer the same protections as federal loans, and you’ll be locked into those terms for years or decades.

Factor in earning potential. If you’re borrowing heavily beyond federal limits, your major matters and you need to know which degrees have the potential to secure the highest paying jobs. A degree that leads to a $40,000 starting salary probably can’t support $100,000 in total debt, no matter how passionate you are about the field.

The Bottom Line

Federal student loans weren’t designed to cover the full cost of college – they were designed to help cover the cost of college as it existed decades ago. That gap between intention and reality leaves today’s students and families with difficult choices: go into significant private debt, attend a less expensive school, work extensively while in school, rely on family wealth, or skip college altogether.

Understanding this gap early in your college planning process isn’t pessimistic – it’s realistic. The students who fare best are those who recognize the limitations of federal aid and plan accordingly, rather than those who assume the government loans will cover their needs and discover the gap too late to adjust their plans.

The system isn’t going to fix itself anytime soon. Your best option is to work within its constraints while advocating for the changes future students deserve.

Related: This topic is part of the broader credit system. For an overview of how credit scores, loans, and debt work together, see our Credit & Debt guide.