The January Effect: Market Myth or Predictable Pattern?

10.6 min read

Updated: Dec 29, 2025 - 09:12:35

The January Effect was a well-documented seasonal stock market anomaly in which equities, especially small-cap stocks, tended to post outsized gains in January. First observed in the mid-20th century and linked to behaviors like year-end tax-loss selling under U.S. capital gains rules, the pattern was real for decades. However, extensive academic research and modern market data show that this effect has largely faded. Increased investor awareness, algorithmic trading, and greater market efficiency have arbitraged away any reliable edge. For investors in 2024–2025, January seasonality is best viewed as historical context, not a strategy.

- Historically real, now unreliable: Research by Kinney (1976) and Rozeff (1976) confirmed higher average January returns, but recent decades show inconsistent results.

- Tax-loss selling mattered—but less now: December selling to realize capital losses once amplified January rebounds, especially in small-cap stocks.

- Market efficiency erased the edge: As the anomaly became widely known, investors front-ran it, aligning with principles of the Efficient Market Hypothesis.

- No dependable signal today: In the last 20 years, January was the S&P 500’s best month only ~20% of the time.

- Core lesson for beginners: Long-term returns come from diversification, discipline, and time in the market, not calendar-based trading.

Every new year brings renewed optimism, fresh resolutions, and for much of the 20th century, a widespread belief that January delivered unusually strong stock market returns. This pattern became known as the January Effect, one of the most widely cited seasonal anomalies in financial history.

The idea traces back to 1942, when investment banker Sidney B. Wachtel documented a tendency for stocks, particularly smaller companies, to outperform in January. His research, based on market data from 1927 to 1942, observed recurring early-year strength in U.S. equities, including the Dow Jones Industrial Average. The findings sparked decades of academic study, debate, and trading strategies built around January’s perceived edge.

For beginner investors today, the key takeaway is nuanced but important: the January Effect was real, it was well-documented, and it gradually faded. Its rise and decline illustrate how markets evolve, how increased awareness and efficiency erode predictable patterns, and why historical advantages rarely persist once they become widely known.

The Original Pattern

The January Effect originally described a tendency for stocks, particularly small-capitalization stocks, to deliver unusually strong returns in January compared with other months of the year.

The pattern was formally documented in the 1970s, most notably by William Kinney Jr. (1976) and Michael Rozeff (1976). Their empirical research showed that average January returns were significantly higher than returns in other months, with the effect concentrated most strongly among smaller firms. This established the January Effect as a measurable seasonal anomaly rather than anecdotal market behavior.

The leading explanation focused on year-end tax-loss selling. Investors would sell losing positions in December to realize capital losses for tax purposes, temporarily depressing prices, especially in less liquid small-cap stocks. In January, renewed buying pressure and portfolio rebalancing often produced sharp rebounds, resulting in outsized early-year gains.

Further studies found the effect to be statistically significant and observable beyond U.S. markets. Research during the late 1970s and early 1980s showed that small-company stocks tended to outperform during the first few trading days of January, and similar seasonal patterns were identified across many international equity markets, though with varying strength.

During the mid-20th century, the consistency of this seasonal return pattern posed a notable challenge to the efficient market hypothesis, which argues that predictable, well-known return advantages should be eliminated as investors arbitrage them away.

The Tax-Loss Harvesting Theory

One widely cited explanation for the January Effect is tax-loss selling. Near year-end, investors in taxable accounts may sell losing positions to realize capital losses that can offset capital gains under U.S. tax rules, which can add temporary selling pressure, often most visible in smaller, less liquid stocks.

In early January, that year-end selling pressure can fade, and some investors may rotate back into similar exposures. However, immediate buybacks can be constrained by the IRS wash-sale rule, which can disallow a loss if a “substantially identical” security is purchased within the 30-day window around the sale.

Research also shows tax-loss selling isn’t the whole story. Studies have found January strength is not limited to prior-year “losers”, and that supports the idea that other forces (like liquidity shifts or institutional “window dressing”) can contribute alongside taxes.

The Pattern’s Decline

For modern investors, the most important twist in the January Effect story is this: it no longer offers meaningful predictive power. While the pattern was once statistically significant, decades of research and real-world market data show that its influence has steadily weakened, especially in large-cap markets like the S&P 500.

Over the past two decades, January has rarely stood out as the strongest month for stocks. In fact, it was the best-performing month for the S&P 500 only four times in the last 20 years, 2012, 2013, 2018, and 2019. That represents roughly 20% of the period, far too inconsistent to support a reliable trading edge or seasonal strategy.

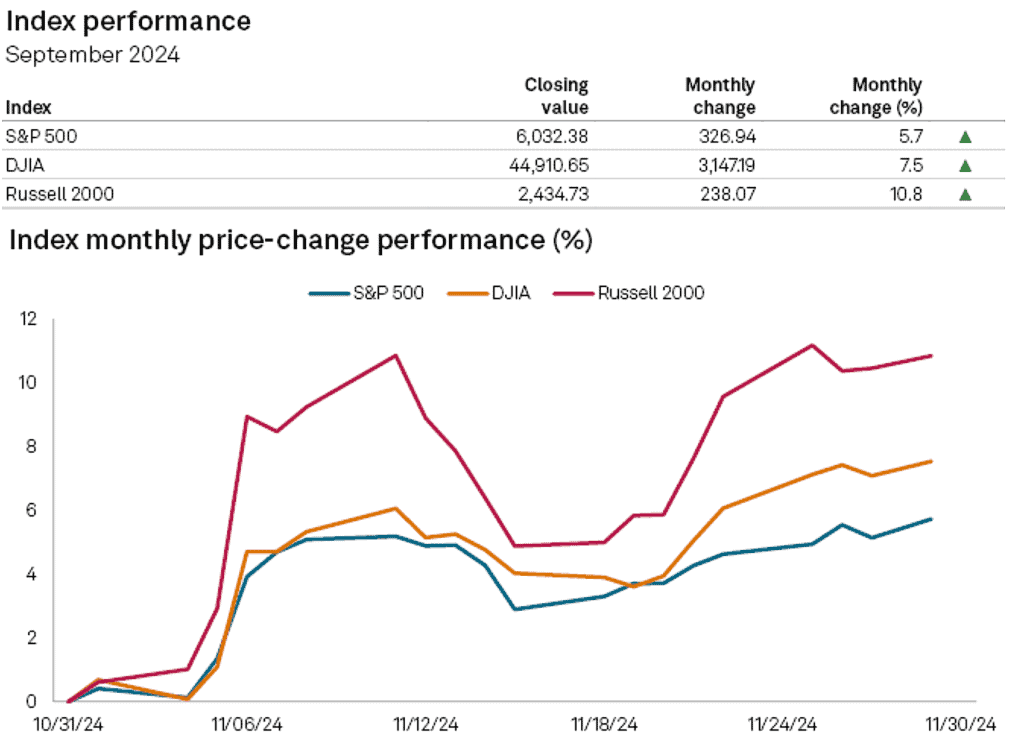

Recent market history reinforces this decline. In 2024, January delivered no exceptional advantage, while November emerged as the strongest month of the year, with the S&P 500 gaining nearly 6%. This divergence highlights how broader macro forces, earnings growth, liquidity conditions, and investor sentiment now play a far larger role in shaping returns than calendar-based effects.

Source: S&P Global

Looking across the 2015–2024 period, January’s performance generally ranked in the middle of the pack compared with other months. Months such as March, April, May, June, October, and November frequently outperformed it, further diluting January’s once-distinct seasonality. What was once viewed as a dependable anomaly has largely faded into ordinary market variation.

Why the Effect Diminished

Economists largely attribute the decline of the January Effect to greater market efficiency, the tendency of financial markets to arbitrage away widely known patterns. Once investors became aware of the anomaly, many attempted to exploit it earlier by shifting purchases into late December, pulling forward gains that had historically appeared in January. Over time, this front-running behavior eroded the calendar-based advantage.

This outcome aligns with the Efficient Market Hypothesis, long associated with Nobel laureate Eugene F. Fama, which holds that predictable excess returns should disappear as information becomes widely known and acted upon. Related ideas are also captured by Andrew Lo’s Adaptive Markets Hypothesis, which describes how market behavior evolves as participants learn and adapt.

Several structural changes accelerated this process:

-

Technological transformation: The rise of algorithmic and high-frequency trading reduced the lifespan of pricing inefficiencies, allowing anomalies to be arbitraged away far more quickly than in earlier decades.

-

Tax regime evolution: Changes in U.S. capital gains taxation and the growing use of tax-advantaged accounts altered incentives for year-end loss realization, weakening one of the January Effect’s original drivers.

-

Global diversification: As cross-border investing expanded, U.S.-specific tax calendars became less influential on overall market flows, diluting localized seasonal effects.

-

Institutional sophistication: Professional fund managers refined year-end rebalancing and cash-management practices, smoothing return patterns that once produced sharp January rebounds.

Together, these forces transformed the January Effect from a persistent seasonal anomaly into a historical case study, illustrating how investor awareness and structural evolution can eliminate once-reliable arbitrage opportunities.

The January Barometer

Running parallel to the January Effect is the “January Barometer,” a market adage summarized as: “As goes January, so goes the year.” The idea suggests that the S&P 500’s performance in January sets the directional tone for the remaining months.

Historically, the relationship has appeared directionally suggestive, though often overstated. Since the mid-20th century, years that began with a positive January were more likely than not to end with gains, and average full-year returns in those cases were meaningfully higher than in years following a negative January. Conversely, when January declined, subsequent full-year returns were weaker on average, sometimes flat or modestly negative.

However, the barometer’s reliability erodes under closer scrutiny. The correlation is far from deterministic, and numerous counterexamples exist, particularly during periods of structural change, post-crisis recoveries, and high-volatility regimes. There have been many years in which January’s direction failed to anticipate the market’s eventual outcome.

As with the January Effect itself, increased awareness and changing market dynamics have reduced any practical edge. Today, the January Barometer survives largely as a historical curiosity rather than a dependable forecasting tool. Statistically interesting? Yes. Consistently tradeable? No.

Small-Cap Stocks and January

Historically, the January Effect appeared most pronounced among small-cap stocks. Their relatively lower liquidity, higher volatility, and greater sensitivity to investor flows made them more vulnerable to year-end selling pressure and early-January rebounds.

Academic research from the 1970s through the 1980s consistently found that small-capitalization stocks outperformed large caps in January, with a disproportionate share of gains occurring in the first few trading days of the month. In some periods, the return differential amounted to several percentage points, helping establish small caps as the core driver of the January Effect.

Over time, however, this advantage weakened substantially. Since the early 2000s, broad small-cap benchmarks such as the Russell 2000 have shown little consistent evidence of persistent January outperformance relative to large-cap indices. While individual years still produce strong January moves, the pattern lacks reliability across cycles.

Today, small-cap performance is better explained by economic conditions, interest-rate expectations, and risk appetitethan by calendar timing. Small caps remain volatile and cyclical, but their edge is no longer seasonal.

International Perspectives

The January Effect was not exclusive to the United States. Academic research has examined similar seasonal patterns across European and Asian equity markets, but the results have been uneven. The strength, timing, and persistence of the effect varied widely by country and period, indicating that it was never a uniform global phenomenon.

Some international findings suggest that seasonal return patterns were influenced more by institutional behavior and taxation frameworks than by geography or climate. Markets such as Canada and the U.K. occasionally displayed January strength comparable to the U.S., particularly in earlier decades. However, evidence that Southern Hemisphere markets consistently shifted the effect to other months based on fiscal calendars is limited, and any such patterns were weaker and far less reliable.

Over time, these non-U.S. seasonal effects have also faded. Increased global capital mobility, faster information dissemination, and the dominance of institutional investors have reduced the impact of country-specific calendar anomalies. As markets became more integrated and efficient, localized seasonal quirks, including international versions of the January Effect, largely dissolved into normal return variation.

What Beginner Investors Should Learn

The evolution of the January Effect offers several lasting lessons for newer investors:

Statistical patterns fade: A pattern observed in historical data does not guarantee future reliability. As markets evolve and participants adapt, many once-persistent anomalies weaken or disappear.

Widely known strategies fail fastest: When a strategy becomes common knowledge, investor behavior shifts to exploit it early, eroding the very advantage it once offered, an example of market efficiency in action.

Costs matter: Attempting to capture small seasonal effects requires precise timing, which increases transaction costs and tax exposure. These frictions often outweigh any theoretical excess return.

Time beats timing: Short-term seasonal trades distract from the most reliable driver of wealth creation: long-term participation in diversified equity markets and the power of compounding.

For investors focused on building durable portfolios, monthly seasonality is largely noise. Remaining invested through all market cycles, strong and weak, offers a far higher probability of success than chasing calendar-based micro-patterns.

Modern January Analysis

Every December, financial media revisits the January Effect. The narrative persists because it offers structure amid market uncertainty and a familiar ritual to open the investing year. In some years, January delivers strong returns and revives old explanations. In others, performance contradicts expectations and fuels claims that the pattern has disappeared.

Modern academic and institutional research suggests a more nuanced reality. The January Effect has not vanished entirely, but it has become statistically inconsistent, difficult to predict, and largely impossible to exploit after costs and taxes. What once appeared as a repeatable seasonal anomaly now behaves more like random variation than a dependable signal.

As 2025 begins, the same question will surface again: Will the January Effect return? The most defensible answer remains unchanged, occasionally yes, often no, and never reliably.

For beginner investors, that uncertainty carries a useful lesson. Long-term success does not require calendar-based strategies. Wealth is built through discipline, diversification, and consistency, not seasonal speculation. Markets do not respond to the calendar, and portfolios perform best when investors don’t either.

This article is part of Mooloo’s Market Cycles & Risk sub-hub, which explains how financial markets behave across economic cycles, stress events, and systemic uncertainty without relying on forecasts or timing narratives.