Solar vs Wind — Which Is the WORST Investment?

7.9 min read

Updated: Dec 20, 2025 - 08:12:48

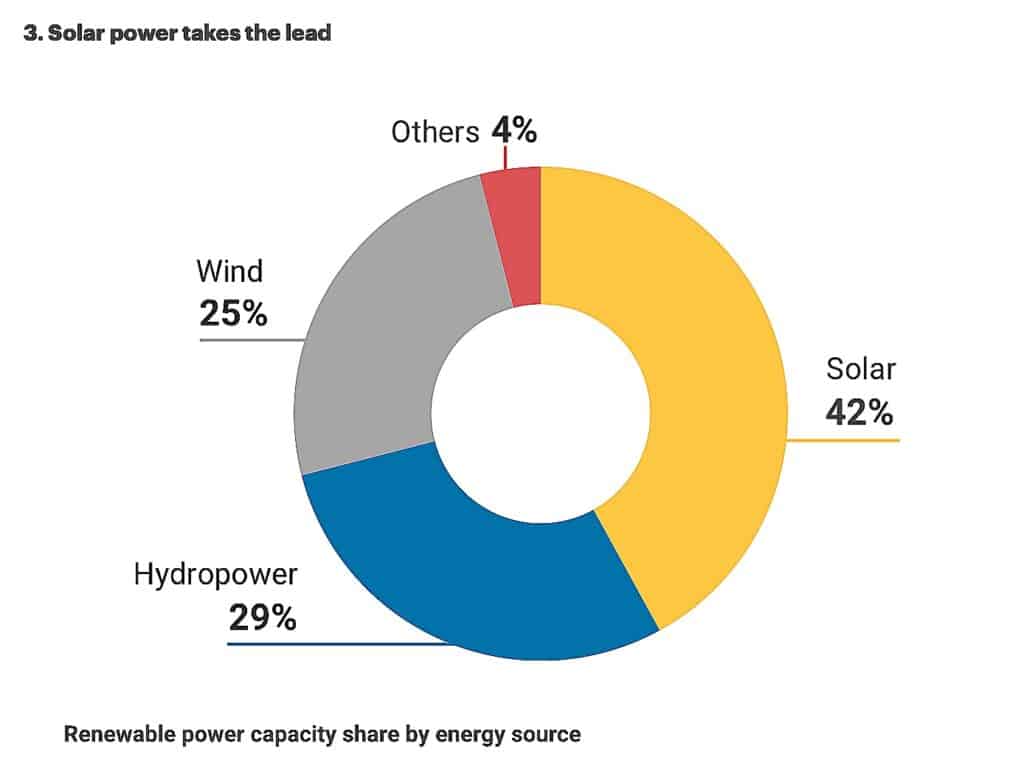

As of 2025, investors chasing the clean-energy transition face a clear divergence: solar is scaling faster, cheaper, and with steadier returns, while wind is struggling under capital costs, policy risk, and financing pressure. Data from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) and International Energy Agency (IEA) show solar now commanding nearly 80% of new renewable capacity growth, underscoring a decisive market shift. For investors, solar remains the more resilient and adaptable play amid rising rates and shrinking subsidies.

- Solar dominates capacity growth: Global solar installations jumped 32% in 2024 versus 11% for wind, reflecting investor preference for scalable, modular projects.

- Financing tilts toward solar: Shorter payback periods and predictable cash flows make solar more bankable than wind, especially as interest rates hover near decade highs.

- Wind faces compounding risks: Offshore wind costs are up 30–50% since 2021, while grid congestion and capture-price discounts erode returns.

- Solar remains volatile but resilient: Oversupply and thin margins persist, yet global overcapacity and rapid deployment continue to drive down costs and sustain growth.

- Investor takeaway: Both sectors are vital to decarbonization, but wind’s economics increasingly rely on subsidies, whereas solar’s path to profitability is more market-driven.

For more than a decade, investors chasing the green energy transition have been told that solar and wind are twin engines of the future. Both promise sustainable returns, massive growth potential, and the moral comfort of decarbonization. Yet in 2025, as interest rates rise, subsidies evolve, and capital costs bite, it’s becoming clear that one of these sectors is a much tougher bet than the other. Both have their risks, but if you’re asking which is the worse investment right now, the numbers point toward wind.

The race for clean power dominance

Global renewable energy deployment continues at record speed, but solar has clearly taken the lead. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), total renewable capacity rose by about 15% in 2024, with solar alone surging 32.2%, adding roughly 452 gigawatts of new generation. Wind expanded by around 11.1%, adding about 113 gigawatts. This sharp contrast highlights the shift in momentum within the renewable sector, as solar continues to dominate global capacity growth.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that renewables will account for the majority of new global power capacity in 2025, with solar maintaining the largest share. The trend reflects where capital, policy support, and innovation are increasingly converging.

Investment data from BloombergNEF shows that solar continues to attract the lion’s share of funding, supported by lower costs, scalable deployment, and faster payback times compared to wind. Investors are clearly voting with their wallets, and solar’s economics are winning the race for clean power dominance.

Source: BloombergNEF

Cost curves and complexity

At first glance, wind appears cost-competitive. Both onshore wind and utility-scale solar now generate electricity for around US$0.06–0.07 per kilowatt-hour globally, often under US$0.05/kWh in favorable regions, making both cheaper than new fossil fuel capacity, according to Wood Mackenzie. But project economics go far beyond levelized cost. Capital intensity, permitting delays, build time, and cash-flow stability ultimately determine investor returns.

Solar’s key advantage is modularity. Utility-scale solar farms can be deployed within months, while large wind projects, especially offshore, often take years. Panels are mass-produced, shipped, and installed with relatively simple logistics. Wind, by contrast, involves massive turbine blades, heavy steel towers, and remote or offshore installation, each stage carrying higher execution risk and cost.

Offshore wind, once hailed as the future of clean baseload power, has turned into a cautionary tale. Developers across the U.K., U.S., and Europe have canceled or renegotiated contracts amid rising material, financing, and maintenance costs. Ørsted, Vestas, and Siemens Gamesa have all reported significant losses linked to supply-chain bottlenecks and inflation. Meanwhile, Chinese manufacturers continue to expand capacity but face thin margins in a fiercely competitive market.

Solar has not been immune, tariff disputes, Chinese overcapacity, and policy shifts have created volatility, but its manufacturing scale continues to drive costs lower. Despite higher interest rates, falling panel prices and faster deployment have helped solar absorb inflationary pressures better than wind, reinforcing its lead in the global clean energy race.

The financing gap widens

Rising interest rates have reshaped renewable energy economics, but wind projects remain more exposed than solar. A 500-megawatt onshore wind farm can take close to a decade to recover its investment, while a solar project of comparable capacity often reaches breakeven several years earlier. In emerging markets, where the cost of capital typically runs between 8% and 10%, these longer payback cycles hit wind projects disproportionately hard.

Financing conditions have also tilted toward solar. Banks and green bond issuers increasingly favor solar projects because they scale faster, face fewer permitting hurdles, and deliver more predictable cash flows. Wind farms, by contrast, contend with community opposition, complex insurance requirements, and higher construction risks. Offshore wind is the most capital-intensive of all, requiring massive up-front investment and exposing developers to uncertain long-term power prices as governments move from fixed feed-in tariffs to competitive auctions. In this environment, the margin for error is vanishingly small

The capture-price problem

Revenue volatility is a silent drag on wind-power economics. When wind generation peaks, often at night or during storms, electricity demand and market prices tend to fall, reducing revenue per megawatt-hour. This “capture-price” effect means that even if a wind farm produces cheap electricity, it earns less than the market average. Solar powerfaces a similar issue during sunny afternoons, but battery storage and demand-response systems are beginning to offset those losses. Wind’s output is harder to manage because it’s less predictable and often located far from major demand centers.

In mature markets such as Germany and the U.K., wind producers typically realize prices about 10–20% below market averages, reflecting this discount effect. Curtailment, being forced to shut down when grids are overloaded, adds further pressure. Wind-heavy regions like Texas in the U.S. and Inner Mongolia in China lose measurable output each year due to grid congestion and limited transmission capacity, highlighting how infrastructure bottlenecks compound the capture-price problem.

Solar’s own cracks

Solar energy may be winning the growth race, but the sector isn’t without flaws. The industry is flooded with capital, leading to fierce competition and shrinking margins. Massive overcapacity in China’s solar manufacturing sector has driven global prices to record lows, squeezing producers even as deployment surges. While this oversupply keeps installation costs down, it threatens profitability and could trigger industry consolidation.

Beyond economics, solar projects face real-world constraints, land-use opposition, lengthy grid interconnection delays, and a growing dependence on battery storage to stabilize output. Policy risk looms as well. In the United States, the Inflation Reduction Act offers generous tax credits for renewables, but any political shift could alter incentives. In Europe, slow permitting and grid congestion continue to hamper new buildouts.

Still, solar’s modular nature and global supply chain provide resilience. Developers can pivot quickly when one market tightens, a flexibility that wind’s site-specific, capital-intensive infrastructure simply cannot match.

The verdict

Both solar and wind remain vital to global decarbonization, but from an investor’s standpoint, the gap between them has widened. Solar power is cheaper to deploy, faster to scale, easier to finance, and more adaptable across markets. Wind, by contrast, is capital-intensive, politically exposed, and increasingly constrained by permitting and revenue challenges. Offshore wind, once the star of institutional portfolios, has become a financial strain amid surging costs and auction failures in the U.K., U.S., and Europe. Even onshore wind, though more economical, faces growing community opposition and grid-connection delays.

As of 2025, if forced to choose between the two, wind looks like the riskier bet. Data from the International Energy Agency show solar accounting for nearly 80% of new renewable capacity growth, while wind expansion slows under higher financing and supply-chain costs. The Boston Consulting Group reports offshore project costs up 30–50% since 2021, pressuring returns. Solar’s profits may be modest, but they’re steadier and less dependent on policy support. Wind’s upside increasingly relies on subsidies and favorable regulation rather than pure market economics.

Source: Boston Consulting Group

What investors should watch

The clean-energy landscape is evolving fast. For investors still bullish on renewables, the key is selectivity, not abandonment. Wind remains viable, but only for players that can solve the industry’s biggest challenges: maintenance costs, logistics, and capital intensity. Next-generation turbine makers and hybrid projects that co-locate wind and solar to smooth power output could eventually earn premium pricing. Still, as a standalone sector, wind is entering a phase of recalibration and consolidation after years of over-optimism and margin pressure.

Solar, by contrast, continues to scale with a momentum that’s hard to match. Global manufacturing capacity now exceeds one terawatt per year, while new thin-film technologies keep driving costs lower. Solar is expected to account for the majority of new renewable capacity additions through 2030. The challenge for investors isn’t whether solar will grow, it will, but how to find profitable exposure in a crowded, hyper-competitive market where margins are razor thin and policy risk remains real.

Both industries are indispensable to a net-zero future, but in financial terms, one is flying closer to the sun and managing not to melt, while the other is still spinning its wheels in the wind.