Presidential Election Cycles: Does Politics Really Move Markets?

11.3 min read

Updated: Dec 29, 2025 - 09:12:11

Historical data shows that U.S. stock market returns often follow a predictable four-year presidential cycle, with weaker performance early in a presidency and stronger gains later, especially in year three. While this pattern is statistically real, it has not provided a reliable or actionable strategy for investors. Market outcomes depend far more on earnings growth, Federal Reserve policy, valuations, and external shocks than on election timing or party control. For beginner investors, the evidence overwhelmingly favors staying invested rather than adjusting portfolios based on election outcomes.

- Year three tends to outperform: Historically, the third year of a presidential term has delivered the strongest average S&P 500 returns, often in the mid-to-high teens, versus a long-run average near 10%.

- Midterm years are often weakest: The second year of a term, which includes midterm elections, has averaged roughly 4–5% returns, well below long-term norms.

- Party control is not a reliable signal: Long-term market gains have occurred under both Democratic and Republican presidents, with no consistent advantage tied to party affiliation.

- Election years are usually positive: Since 1928, presidential election years have produced positive stock returns about 80%+ of the time, slightly above average.

- Patterns ≠ strategy: Transaction costs, taxes, and unpredictable shocks make timing portfolios around elections far less effective than staying invested.

Every four years, as U.S. presidential elections approach, investors ask the same questions: Will this election move markets? Should I adjust my portfolio based on who might win? Does the political party in power matter for my investments? For beginner investors encountering these concerns for the first time, the relationship between presidential politics and market performance is both more predictable, and far less actionable, than it initially appears.

The Presidential Election Cycle Theory, popularized by Yale Hirsch in the Stock Trader’s Almanac beginning in the late 1960s, suggests that stock market returns tend to follow a recurring four-year pattern aligned with the presidential term. Under this framework, market returns have historically been weaker, on average, during the first two years of a presidency and stronger during the latter two years, particularly the third year. Decades of market data show that this pattern exists in long-term averages, but they also demonstrate why attempting to time investment decisions around it has not reliably produced superior results.

Source: Wealth Management

The Four-Year Pattern

Long-term data on S&P 500 returns does show a presidential cycle effect, with the third year of a presidential term historically delivering the strongest average performance. Across datasets covering roughly 1930s–2023, third-year returns have averaged in the mid-to-high teens, clearly above the market’s long-run annual average of about 10%.

By contrast, the first and second years of presidential terms have tended to produce below-average returns, with the second year, coinciding with midterm elections, consistently ranking as the weakest. Average second-year returns typically fall in the low-to-mid single digits, well below the long-term mean. Fourth-year returns generally improve but remain less consistent than year three.

Source: Wealth Management

The pattern also appears in return frequency. Third years have produced positive returns in roughly 85–90% of cases, compared with about 70% across all calendar years. Years one and two show materially lower hit rates, particularly year two, which posts gains only around half to three-fifths of the time, depending on the sample period.

Another way to examine the data reveals similar patterns. The combined returns of years three and four average 24.5%, while the first two years combined deliver only 12.5%. The back half of presidential terms consistently outperforms the front half regardless of which party holds power or what economic conditions prevail.

More granular analysis shows year two, the midterm election year, typically represents the weakest of the four. Historical data pegs second-year average returns at just 4.6%, far below the market’s long-term 10% average annual gain. This weakness creates an opportunity for the subsequent year’s strength, as markets often rebound from midterm doldrums.

Source: Wealth Management

Why the Pattern Exists

Several theories attempt to explain the presidential cycle’s persistence. The most compelling involves the predictable shift in presidential priorities across a four-year term.

New presidents typically focus their first two years on delivering campaign promises and pursuing ambitious, sometimes controversial policies. This period often includes difficult fiscal decisions, spending cuts, tax increases, regulatory changes, that may slow economic growth in the short term. These policy changes create uncertainty that markets dislike. The first year often sees significant legislative battles as new administrations push their agendas through Congress.

By year two, with midterm elections approaching, political attention shifts toward maintaining congressional support. However, midterm campaigns typically generate negative advertising and heightened partisan conflict. Markets face uncertainty about potential changes in congressional control that could stall or reverse first-year policy initiatives. Historical data shows 57% probability that recessions occur during the year following presidential elections, compared to 22%, 30%, and 17% in other cycle years, suggesting presidents have been particularly unlucky in their timing or that their early policies sometimes contribute to economic slowdowns.

Source: T. Rowe Price

Year three brings a dramatic shift in priorities. With re-election or maintaining party control at stake, presidents focus intensely on stimulating the economy and delivering strong economic performance. Policy initiatives during year three tend toward economic stimulus, regulatory relief, and other measures designed to boost growth and employment. Presidents want voters feeling prosperous when they enter the voting booth the following year.

This economic stimulus extends beyond direct policy. Government spending often increases. Infrastructure projects accelerate. Appointees to key regulatory positions receive instructions to facilitate rather than impede economic activity. The cumulative effect of these pro-growth initiatives typically shows up in stronger corporate earnings and, consequently, higher stock prices.

Year four, the election year itself, brings mixed influences. Markets must digest uncertainty about potential leadership changes and policy direction. However, the stimulative effects from year three often carry forward. Additionally, neither party wants a weak economy during an election year, creating bipartisan incentive to avoid policy moves that might trigger economic slowdowns.

Election Year Performance

Election years themselves show notable patterns beyond the four-year cycle. Since 1928, the S&P 500 has averaged returns of around 11.3% during presidential election years, modestly above the index’s long-term average. Stocks have also produced positive returns in approximately 83% of election years, a higher success rate than the historical average across all calendar years.

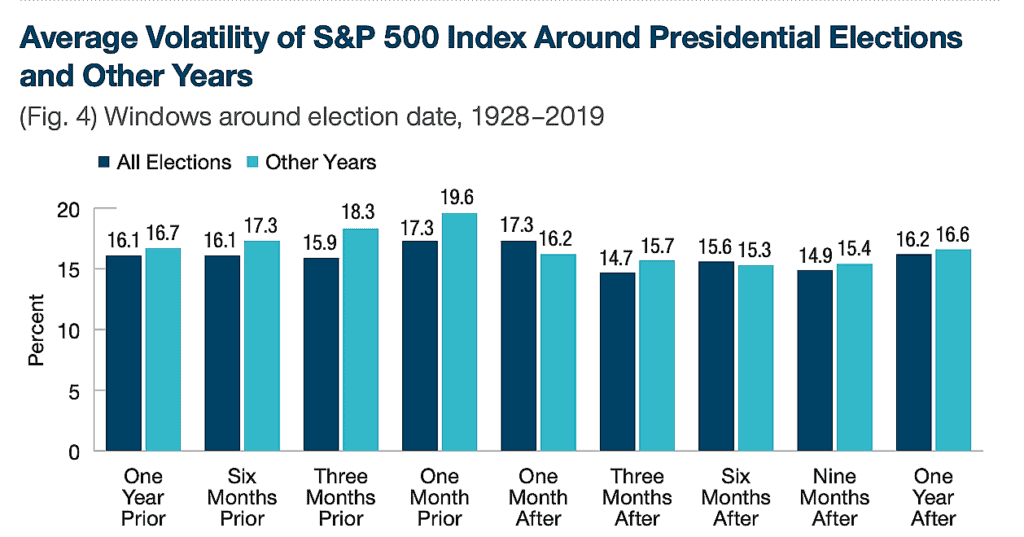

A 2024 analysis by T. Rowe Price found that stock market returns six and twelve months after Election Day were meaningfully lower than comparable periods in non-election years. This finding aligns with the broader presidential cycle theory, which observes that the first year of a new administration often underperforms as policy changes, fiscal adjustments, and regulatory uncertainty weigh on investor sentiment.

The timing within election years also matters. Historically, the first half of election years has tended to be weaker, while the second half has delivered stronger returns as uncertainty surrounding election outcomes diminishes. Long-term data show that the third quarter of election years has delivered the highest average return, at roughly 6.2%, reflecting markets transitioning from political uncertainty to clarity as Election Day approaches.

The final quarter of presidential election cycles exhibits one of the highest proportions of positive returns, at approximately 83.3%, although average fourth-quarter returns are more modest, near 2.5%. Markets typically respond positively to the resolution of election uncertainty itself. In practice, certainty about who will govern often matters more than which party wins, as reduced uncertainty lowers risk premiums even when investors may prefer a different political outcome.

Does Party Affiliation Matter?

For investors focused on which party wins, historical data offers clear guidance: party affiliation matters far less than commonly believed. Long-term stock market performance has been positive under both Democratic and Republican presidents, driven more by economic fundamentals than political labels.

Market data since the early 20th century shows sustained upward trends across presidencies from both parties. While some studies report differences in average or median returns depending on party control, those differences vary by time period and methodology and do not form a reliable investment signal.

Individual presidencies highlight this point. During President Obama’s tenure, the S&P 500 delivered a 235% total return, or about 16.4% annualized. President Trump’s first term produced an 81.4% total return. Under President Biden’s four-year term through 2024, the S&P 500 returned approximately 57.8% in total, despite periods of high inflation and low approval ratings.

Source: Nasdaq

Returns also differ under various government configurations, but not in a consistent or predictable way. Using long-term S&P 500 data, average annual returns have been approximately 14.5% under unified Republican control, 14.0% under unified Democratic control, 7.3% when a Republican president faced a divided Congress, and 16.6% when a Democratic president governed with divided control.

Taken together, these figures show that markets do not reliably favor one party or governing structure. Performance depends far more on the broader economic environment, monetary policy, valuations, and external shocks than on which party controls Washington.

The 2024-2025 Example

The 2024 presidential election and Donald Trump’s victory provide a contemporary case study. By the end of 2024, the S&P 500 returned approximately 25–26% for the full year, including dividends, well above the long-term average annual return for the index (around 10%) and a very strong result historically.

November 2024, the election month, saw a particularly strong performance, with the S&P 500 up about 5.7%, making it the best monthly gain of the year. S&P Global Markets appeared to rally after the election outcome as uncertainty resolved, giving investors clearer expectations about policy direction.

Looking ahead to 2026, presidential-cycle theory suggests a historically softer performance period. According to data on the Presidential Election Cycle Theory, the second year of a presidential term has tended to be the weakest of the four in terms of average stock market returns, with significantly lower average gains than other years. That pattern reflects the theory’s observation that markets often strengthen in later years of a term as incumbents may pursue stimulus-oriented policy ahead of elections, but traditional historical patterns do not guarantee future results.

However, these patterns are statistical averages, not deterministic laws. Market performance is shaped by many factors beyond the electoral calendar, including Federal Reserve policy, earnings growth, global economic conditions, geopolitical events, and technological innovation.

The Predictive Power—And Limits

The presidential cycle theory has legitimate statistical support. From 1928 through recent election cycles, third-year presidential terms have produced positive S&P 500 returns roughly 75–76% of the time, well above the about 65–67% success rate across all calendar years. This consistency makes the pattern difficult to dismiss as pure coincidence.

However, predictive tendency does not equal profitability. Several factors undermine attempts to profit from the presidential cycle:

The pattern reflects averages across many presidencies. Individual four-year terms often deviate sharply. External shocks, wars, pandemics, financial crises, and technological disruptions, can overwhelm any seasonal or cyclical effect. The 2008 financial crisis, for example, delivered severe losses despite occurring in what historically should have been a stronger year-four and year-one window.

Even when the pattern holds directionally, return magnitude varies widely. Knowing year three typically outperforms year two does not indicate whether returns will be 15% versus 10% or 35% versus negative 5%. That distinction is critical for portfolio decisions yet remains unpredictable.

Transaction costs and taxes further erode returns from tactical moves around the cycle. Shifting between more and less aggressive allocations based on the presidential calendar introduces trading costs, can trigger capital-gains taxes, and increases the risk of mistiming transitions between cycle phases.

What Beginner Investors Should Know

The presidential election cycle is one of the most studied seasonal patterns in market history. Unlike many calendar-based effects that weakened once widely known, the presidential cycle has broadly maintained its general shape in long-term data. This persistence suggests structural factors, such as policy timing, fiscal incentives, and political uncertainty, continue to influence markets regardless of which party holds office.

For practical investing, however, these historical tendencies do not translate into a reliable trading strategy. Investors cannot consistently time market entry and exit around the four-year cycle while maintaining discipline, minimizing costs, and avoiding behavioral mistakes.

What investors can do is use the cycle as context. When year two delivers weaker returns, this often aligns with long-term averages rather than signaling fundamental problems. When year three produces strong gains, this may reflect normal cycle dynamics rather than validating investment decisions or stock-picking skill.

Political developments will always attract attention and provoke emotion. Markets react to elections, policy announcements, and legislative conflict. The presidential cycle framework reminds investors that beyond daily headlines, broader historical tendencies exist, driven more by incentives and policy timing than short-term news.

These patterns are interesting, well documented, and useful for perspective. They are far less useful for portfolio decisions that require precise timing, incur transaction costs, and create tax consequences. Over long periods, markets have trended upward regardless of which party controls government. For beginner investors, staying invested across all four years of presidential cycles has historically outperformed moving in and out based on the calendar.

Investment success depends far more on starting early, maintaining discipline, diversifying broadly, and minimizing costs than on any political cycle or party preference. Focus on what you can control, your savings rate, asset allocation, and investment horizon, rather than political dynamics that shift every four years.

This article is part of Mooloo’s Market Cycles & Risk sub-hub, which explains how financial markets behave across economic cycles, stress events, and systemic uncertainty without relying on forecasts or timing narratives.