Coal Mining vs. Oil Drilling: Which Is The WORST Investment?

7.6 min read

Updated: Dec 20, 2025 - 08:12:38

For investors eyeing energy stocks in 2025, both coal mining and oil drilling represent sectors in structural decline. Coal is collapsing outright, bankruptcies, shrinking demand, and regulatory pressures have erased decades of value. Oil drilling, particularly in U.S. shale, survives on debt and diminishing returns, with global demand projected by the International Energy Agency to peak around 2030. The energy transition is not a future trend, it’s the current market reality.

- Coal’s collapse is terminal: Over 50 U.S. producers have gone bankrupt since 2010, and retirements of coal-fired plants continue to outpace new projects.

- Oil’s decline is slower but certain: Shale drillers burned roughly –$300 billion in free cash flow over the past decade, and many remain overleveraged “zombie” firms.

- Energy transition accelerates: Renewables are projected to supply nearly half of global electricity by 2024, undercutting both coal and oil economics.

- Debt is oil’s ticking clock: More than $150 billion in bankruptcies since 2015 reflect an unsustainable financial structure.

- Smarter alternative: Avoid both fossil sectors, invest instead in renewables, batteries, and grid technologies that benefit from policy and capital tailwinds.

When novice investors look for the next energy boom, coal mining and oil drilling might seem like bold bets worth taking. After all, the world still runs on fossil fuels. Yet the reality is more complex. Over the past decade, coal producers have faced waves of bankruptcies and declining demand, while oil and gas companies have endured severe boom-and-bust cycles. Both industries remain deeply exposed to price volatility, regulatory pressure, and the global energy transition. If you’re choosing between these two pillars of the old energy order, you’re essentially deciding between a sector slowly fading and one still burning brightly, but under a tightening clock.

The Case Against Coal Mining: Terminal Decline

Coal mining isn’t just struggling, it’s collapsing. Over 50 U.S. coal companies have filed for bankruptcy since 2010, wiping out shareholders and erasing decades of market value. In 2019 alone, eight producers, including Murray Energy, once the nation’s largest privately held coal miner, went under.

The industry’s core problem is economic, not political. Natural gas prices collapsed during the 2010s, making gas-fired power plants far cheaper to operate. At the same time, renewable energy costs plunged, undercutting coal in nearly every major power market. Between 2010 and 2019, U.S. utilities retired more than 546 coal-fired units, about 102 GW of capacity, roughly one-third of the nation’s coal fleet.

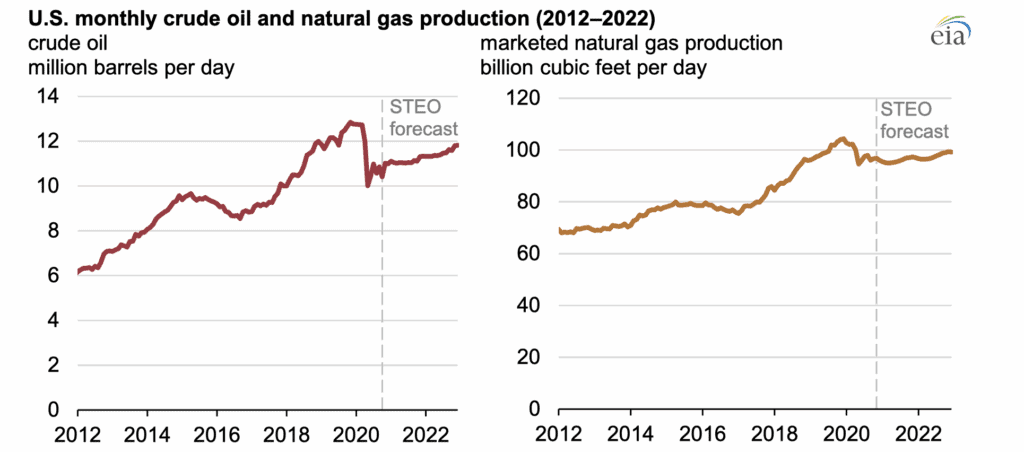

Source: EIA

Coal production collapsed in tandem. The number of active U.S. coal mines fell from 1,435 in 2008 to 671 by 2017, according to the Energy Information Administration. Even industry giants like Peabody Energy, Arch Resources, and Alpha Natural Resources sought bankruptcy protection. These weren’t fringe operators, they were once the pillars of American coal.

The environmental burden compounds the decline. When companies fail, their reclamation bonds often fall short, leaving states to cover cleanup costs that can stretch into billions. And while global demand remains high in China and India, the International Energy Agency expects coal use in advanced economies to keep shrinking, with global demand plateauing before 2030. Politicians may talk about reviving coal, but the market has already moved on.

The Case Against Oil Drilling: Debt-Fueled Disaster

Oil drilling, especially U.S. shale, looked like an American success story until the bills came due. For much of the 2010s, producers tapped cheap credit and promised that fracking would deliver strong returns at lower oil prices. The reality was far rougher: the sector spent years burning cash and relying on capital markets to plug the gap. Over 2010–2019 alone, U.S. shale’s cumulative free cash flow was roughly –$300 billion, underscoring a business model that struggled to self-fund.

Source: CSIS

Bankruptcies surged when prices collapsed in 2020, but the cracks predated COVID. Since 2015, more than 230 North American oil and gas producers with at least $152 billion in debt have filed for bankruptcy. Industry-wide, counting oilfield services and midstream too, Haynes and Boone has tracked over 600 energy bankruptcies since 2015. In 2020 alone, 45 E&P companies went under, the second-highest total since the 2014–16 bust.

The debt loads in marquee cases were massive. Chesapeake Energy, Diamond Offshore Drilling, and California Resources Corp. all sought Chapter 11 protection in 2020, multi-billion-dollar failures that epitomized years of overextension and volatile cash flows.

The economic engine behind shale was also weaker than advertised. New wells decline rapidly, often 60–70% in the first year, which forces constant drilling just to keep production flat and keeps capital needs high. That treadmill works only when credit is abundant and investor patience is long.

Finally, the energy transition adds structural risk. The International Energy Agency projects global oil demand to peak around 2030, with supply capacity outpacing demand into the next decade, a setup that could pressure prices and investment economics even if oil doesn’t vanish overnight. Forecasts differ (OPEC, for instance, is more bullish), but the direction of travel is clear: slower growth, tighter capital discipline, and fewer easy wins.

The Critical Difference: Speed of Decline

Both industries are in structural decline, but their timelines differ sharply. Coal’s fall has been faster and more visible. Global coal production and power generation peaked in the 2010s, and despite short-term rebounds, long-term demand is set to shrink as retirements outpace new projects. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects global coal use to plateau through 2026 before entering permanent decline, with no pathway for a meaningful comeback.

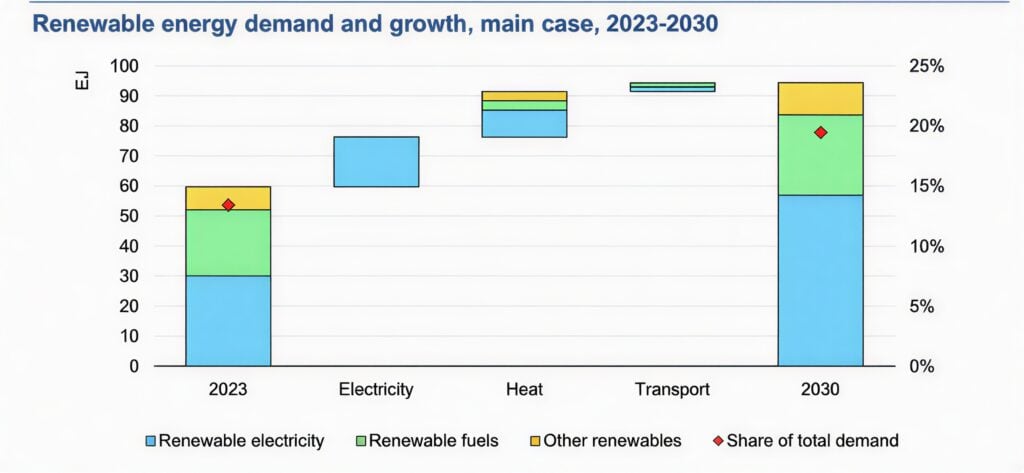

Oil drilling, by contrast, has a longer but narrowing runway. The world still depends on petroleum for transportation and industry, but the transition is accelerating. The IEA’s Global EV Outlook projects nearly ten times as many electric vehicles on the road by 2030, while its Renewables 2024 report forecasts that renewables will supply almost half of global electricity, up from about 30% today. That shift points to slower but inevitable erosion in oil demand growth.

Source: IEA

Debt dynamics underscore the contrast. Many coal producers have already collapsed under financial stress, while oil firms, particularly U.S. shale drillers, remain heavily leveraged. A significant portion are “zombie” companies, technically solvent but unable to generate sustainable returns at moderate oil prices. In short, coal’s demise has been decisive; oil’s reckoning is still unfolding.

The Verdict: Coal Is Worse (But Both Are Terrible)

If forced to choose the worse investment, coal mining edges out oil drilling, but only slightly. Coal faces near-total obsolescence with no credible recovery path. The fuel is being phased out worldwide due to climate mandates, poor economics, and cheaper renewable competition. Every major trend in the global energy transition works against coal’s survival.

Coal’s bankruptcy wave has been more severe and final than oil’s. Dozens of U.S. coal producers have collapsed, and many liquidated entirely, leaving behind environmental liabilities and unpaid cleanup obligations. When your product is being systematically eliminated from the market, there’s no viable restructuring path back to profitability.

Oil drilling, while deeply troubled, retains limited relevance. The world still depends on petroleum for transport, petrochemicals, and heavy industry, even as demand peaks and slowly declines. Some oil companies with low-cost production and strong balance sheets may adapt through diversification or carbon-capture projects. Coal firms lack that option.

However, oil’s apparent advantage hides a structural flaw, debt. In 2020 alone, over $98 billion in oil and gas debt entered bankruptcy court, compared with $70.3 billion during the previous oil bust, according to Haynes and Boone. Many U.S. producers remain technically insolvent, surviving on cheap credit and lenient lenders. Once financial conditions tighten, another bankruptcy wave could erase what little value remains, proving that in this race to the bottom, coal may already be dead, but oil is dying on borrowed time.

A Better Alternative: Avoid Both Entirely

Here’s the advice that bears repeating: the best investment decision is to avoid both coal and oil. Each faces structural decline driven by climate policy, technological progress, and economic headwinds. Why choose between two losing propositions?

If you’re drawn to the energy sector, focus instead on companies benefiting from the global energy transition rather than resisting it. Renewable energy developers, battery manufacturers, electric vehicle producers, and grid infrastructure firms are positioned to thrive as capital shifts away from fossil fuels. These sectors are riding tailwinds, not fighting headwinds.

For investors still tempted by fossil fuels, understand that you’re making a short-term tactical bet, not a long-term investment. You’re gambling on timing the market, getting in and out before the next bankruptcy wave hits. Some traders profit from those swings, but most investors don’t.

The transition to clean energy is accelerating globally and, according to leading energy experts, it’s unstoppable. Betting against that momentum by investing in coal or oil means betting against economic, technological, and policy forces moving in the opposite direction.

Between the two, coal remains the worse investment, its future viability is effectively zero, but both sectors have destroyed far more wealth than they’ve created. The smartest move is recognizing that sometimes, the best investment is the one you don’t make.