Dividends vs Capital Gains: The Tax Trade-Off Explained

13.5 min read

Updated: Jan 8, 2026 - 02:01:34

Stock

Stock returns come from two sources, dividends and capital gains, but the “better” choice depends on taxes, account type, and income needs, not headline yield. Dividends provide regular, taxable cash flow, while capital gains concentrate returns in price appreciation that is taxed only when realized. In practice, both contribute to total return, but they differ meaningfully in tax timing, predictability, and planning flexibility. For long-term investors in taxable accounts, growth-oriented strategies can often maximize after-tax compounding through deferral. For retirees or lower-bracket investors, qualified dividends can provide reliable income with manageable tax costs. The key decision is structural: how returns are delivered and taxed across accounts, not whether income or growth is inherently superior.

- Total return is the same, structure is not: An 8% return from dividends plus growth equals 8% from growth alone, but taxes and cash flow can differ materially.

- Dividends trigger current taxes: Qualified dividends are taxed annually at preferential rates, while non-qualified dividends are taxed as ordinary income.

- Capital gains offer tax control: Gains are taxed only when shares are sold, allowing long-term deferral and, under current law, a potential step-up at death.

- Account type drives efficiency: Tax-inefficient income (REITs, high dividends) often fits better in IRAs/401(k)s; growth assets are usually more efficient in taxable accounts.

- No universal winner: The optimal mix depends on income needs, tax bracket, time horizon, and portfolio structure, not dividend yield alone.

Stock returns come in two primary forms: dividends and capital gains. Dividends are cash payments distributed to shareholders, typically funded from a company’s current profits or accumulated retained earnings. Capital gains reflect the increase in a stock’s market price over time and are realized only when shares are sold. Together, dividends and realized capital gains make up an investor’s total return, but they differ meaningfully in how returns are received, when taxes are triggered, and how they affect cash flow.

Understanding this distinction is not about deciding which return type is inherently superior. Dividends and capital gains serve different purposes and suit different investor needs. Income-producing investments can provide regular cash flow, while growth-oriented investments rely more heavily on price appreciation and deferred taxation. The choice between them shapes tax timing, portfolio cash flow, and long-term planning outcomes, making it a strategic consideration rather than a value judgment.

Income Versus Growth: Two Paths to the Same Goal

Total return, the complete measure of investment performance, includes both dividends and price appreciation. A stock that pays a 3% dividend yield and appreciates 5% delivers an 8% total return. Another stock that pays no dividend but appreciates 8% produces the same mathematical result through a different return structure.

From a purely theoretical total-return perspective, the split between dividends and price appreciation does not change the headline return. Eight percent is eight percent. In real-world investing, however, taxes, cash-flow timing, and portfolio planning considerations make the composition of returns materially important.

Dividend-focused investments distribute a portion of company earnings directly to shareholders, typically on a quarterly basis. These payments can provide a predictable source of cash flow without requiring the sale of shares, which is especially valuable for investors seeking current income. Dividends, however, are discretionary and can be reduced or suspended during periods of financial stress.

Growth-focused investments reinvest earnings into business expansion rather than paying them out. Returns accrue primarily through share-price appreciation and are not realized as cash until shares are sold. This structure often allows greater tax deferral, making growth strategies attractive for investors in accumulation phases who do not need current income.

Research cited by Hartford Funds shows that companies with long histories of paying and increasing dividends have delivered competitive long-term total returns, often with lower volatility. The choice between income and growth strategies, however, is not about which performs better in isolation, it is about how returns are delivered, taxed, and integrated into an investor’s broader financial plan.

Timing and Predictability Differences

Dividends are announced in advance and paid on a regular schedule, making them generally more predictable than capital gains, particularly for established companies with long histories of consistent payouts. Dividend payments are driven by a company’s earnings and cash flow rather than short-term share price movements, which allows many firms to maintain dividends even during periods of market volatility. While dividend cuts do occur, especially during economic downturns, they are typically associated with underlying business stress rather than normal price fluctuations.

Capital gains, by contrast, are uncertain in both timing and magnitude. Share prices fluctuate continuously based on market sentiment, company performance, macroeconomic conditions, and external events. An investor may hold a stock for many years before realizing a gain, or the investment may decline in value, resulting in a loss instead.

These differences create distinct planning considerations. Dividends are taxable in the year they are received, regardless of whether the investor reinvests them or needs the cash. This creates a predictable but unavoidable tax obligation aligned with the dividend payment schedule.

Capital gains are taxed only when realized through a sale, giving investors control over the timing of the tax event. An appreciated stock can be held for many years, or even decades, without triggering tax, and in some cases may never be taxed if held until death and passed on with a stepped-up cost basis under current law.

This ability to defer taxation represents a structural advantage of capital gains over dividend income. While dividends generate immediate, taxable cash flow, capital gains allow tax obligations to be delayed, often for extended periods, providing greater flexibility in long-term tax and financial planning.

Tax Treatment: Why Qualified Status Matters

Both dividends and long-term capital gains receive preferential tax treatment compared to ordinary income, but only if specific IRS conditions are met. As outlined in IRS Publication 550, the distinction between qualified and non-qualified dividends determines which tax rates apply.

Qualified Dividends and Preferential Rates

Qualified dividends are taxed at the same preferential rates as long-term capital gains: 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on taxable income. For 2024, these brackets are:

-

0% rate for single filers with taxable income up to $47,025 (up to $94,050 for married filing jointly)

-

15% rate up to $518,900 for single filers ($583,750 for married filing jointly)

-

20% rate above those thresholds

For dividends to qualify, they must be paid by U.S. corporations or qualified foreign corporations, and the investor must hold the stock for more than 60 days during the 121-day period that begins 60 days before the ex-dividend date. This holding-period rule is designed to prevent short-term trading strategies intended solely to capture dividend payments.

Most regular dividends from established U.S. corporations qualify when these holding requirements are met. Dividends from REITs and certain pass-through structures generally do not qualify and are taxed as ordinary income, though portions of REIT distributions may be classified differently depending on their underlying source.

Non-Qualified Dividends and Ordinary Income Treatment

Non-qualified dividends are taxed at ordinary income tax rates, which can be as high as 37% at the federal level, before considering any applicable surtaxes. For high-income investors, this can create a significant tax disadvantage compared to long-term capital gains. A $1,000 non-qualified dividend can result in materially higher federal tax liability than a $1,000 long-term capital gain taxed at the 20% preferential rate.

This tax differential helps explain why income-producing assets that generate non-qualified distributions, such as REITs, are often better suited for tax-advantaged retirement accounts, where current tax treatment is deferred or eliminated. In taxable accounts, the higher tax burden can materially reduce after-tax returns.

Capital Gains and Holding Period Requirements

Long-term capital gains from assets held more than one year generally receive the same preferential tax rates as qualified dividends. Short-term capital gains from assets held one year or less are taxed as ordinary income, just like non-qualified dividends.

The key distinction is control. Investors can typically choose when to realize capital gains by deciding when to sell an asset, allowing them to meet long-term holding requirements and manage the timing of taxation. Dividend income, by contrast, is taxed when paid, with qualification determined by issuer type and holding period, leaving investors with limited ability to defer recognition once the dividend is declared.

Why the “Better” Choice Depends on Structure, Not Yield

Debates over whether dividend stocks or growth stocks deliver superior returns often miss the central issue. The effectiveness of either approach depends far more on an investor’s account structure, tax treatment, income needs, and time horizon than on headline yield or historical performance. Dividends and capital gains are simply different mechanisms for delivering total return, and their suitability varies based on where and how investments are held.

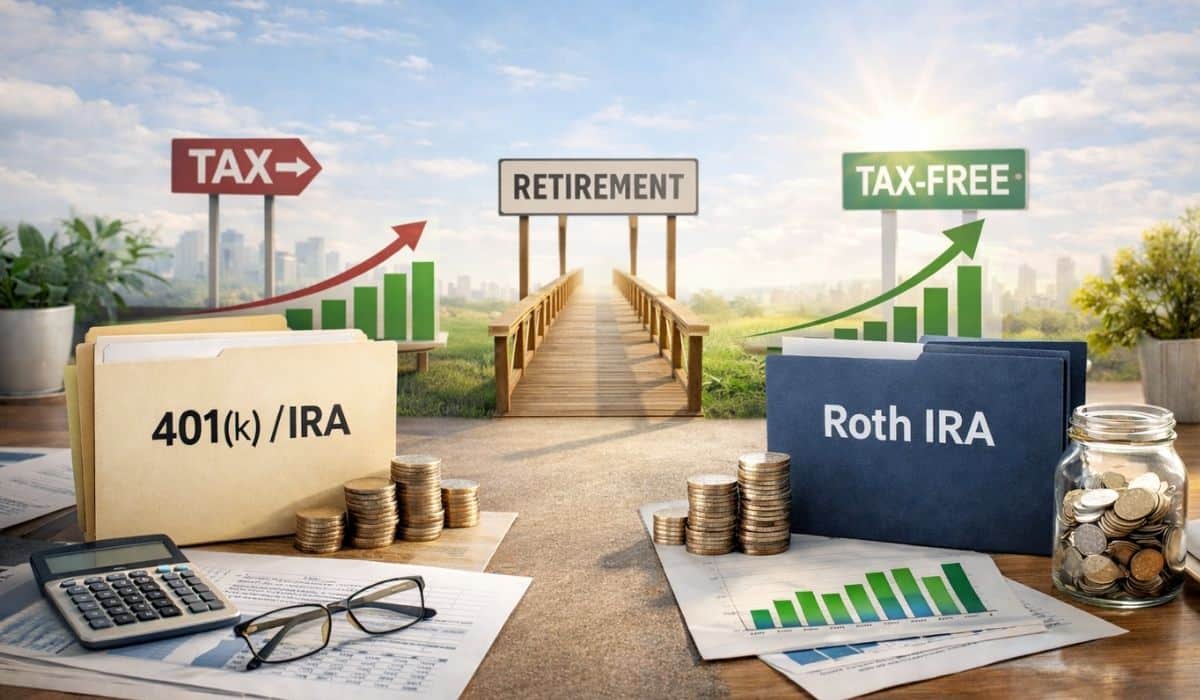

Tax-Deferred and Tax-Free Accounts

Within tax-advantaged accounts such as IRAs and 401(k)s, the distinction between dividends and capital gains largely disappears from a current tax perspective. Neither form of return creates immediate tax liability, allowing investments to compound without annual tax drag. In these accounts, investors can focus primarily on total return, diversification, and risk alignment rather than tax efficiency.

High-yield dividend stocks and REITs, which can be tax-inefficient in taxable accounts, often fit well inside retirement accounts. Likewise, actively traded growth strategies that generate short-term gains do not trigger current taxes when held in tax-deferred plans. Research from Employee Benefit Research Institute shows that, within tax-protected accounts, asset allocation and risk management matter far more than whether returns arrive through dividends or price appreciation. While future withdrawals from traditional accounts will be taxed as ordinary income, the dividend-versus-growth distinction during accumulation remains secondary.

Taxable Accounts During Accumulation

In taxable accounts held for long-term growth, investments that minimize current distributions are typically more tax-efficient. Growth-oriented stocks allow returns to compound as unrealized capital gains, deferring taxation until shares are sold, potentially decades later. This deferral preserves more capital for compounding over time.

For example, a growth stock that appreciates 10% annually generates no current tax liability if no shares are sold. By contrast, a stock delivering the same 10% total return through a 4% dividend and 6% price appreciation creates immediate taxable income. On a $10,000 investment, a 4% dividend produces $400 in income, resulting in $60 of federal tax for an investor in the 15% qualified dividend bracket. Over long horizons, repeatedly paying taxes on distributions reduces the amount of capital available to compound, often leading to lower after-tax wealth compared to tax-deferred appreciation.

Taxable Accounts for Income Needs

For investors who require regular income, commonly retirees, dividends can play a valuable role despite their tax cost. Dividend payments provide consistent cash flow without requiring the sale of shares, helping preserve portfolio structure and reducing the need for ongoing trade execution. For investors in lower tax brackets, qualified dividends may even be taxed at a 0% federal rate, making them an efficient income source.

While capital gains can also be harvested systematically to generate income, this approach requires periodic planning and execution, which some investors find less intuitive than receiving scheduled dividend payments. The decision in taxable income-oriented portfolios is not purely about minimizing taxes; it involves balancing tax efficiency with cash-flow reliability, behavioral comfort, and portfolio sustainability. Research from Vanguard shows that both dividend-based and total-return withdrawal strategies can be effective when aligned with an investor’s spending needs, tax bracket, and risk tolerance.

How Dividend and Capital Gains Strategies Interact With Other Tax Decisions

The dividend-versus-growth choice does not exist in isolation. It connects directly to broader tax-planning decisions that affect after-tax returns, cash flow, and long-term flexibility.

Asset Location Across Account Types

Tax-efficient investing often involves placing tax-inefficient income sources in tax-advantaged accounts and holding more tax-efficient assets in taxable accounts. The key distinction is not simply “dividends versus growth,” but how income is taxed. Ordinary income, such as bond interest, many REIT distributions, and frequent short-term gains, often fits better inside tax-deferred or tax-free accounts where it does not create current tax liability. By contrast, growth-oriented equities and broadly diversified stock funds can be relatively tax-efficient in taxable accounts because unrealized gains are deferred and qualified dividends may receive preferential tax rates. Proper asset location can enhance after-tax returns without changing the underlying investments or increasing risk.

Tax-Loss Harvesting Opportunities

Holdings with meaningful price volatility can create opportunities for tax-loss harvesting by selling positions at a loss and reinvesting in similar but not substantially identical assets to avoid the wash sale rule. Harvested losses can offset realized capital gains and, if losses exceed gains, up to $3,000 of ordinary income per year, with unused losses carried forward.

A critical correction is that tax-loss harvesting opportunities are driven by volatility and timing, not by whether a stock pays dividends. Dividend-paying stocks can still experience significant price declines, and dividends do not mechanically protect against losses. In practice, share prices typically adjust downward around the ex-dividend date, so dividend income does not create a true cushion against price declines. Dividends contribute to total return over time but do not eliminate loss-harvesting opportunities.

Required Minimum Distributions

Retirees face required minimum distributions (RMDs) from traditional retirement accounts based on birth year, generally beginning at age 73, with the starting age shifting to 75 for those born in 1960 or later. RMDs from traditional IRAs and 401(k)s are taxed as ordinary income, regardless of whether the underlying returns inside the account came from dividends, capital gains, or interest. For RMD purposes, the character of investment returns inside the account is irrelevant.

This means that in retirement, the dividend-versus-growth distinction matters most in taxable accounts, where different income types can still receive different tax treatment. Within traditional pre-tax retirement accounts, both dividend and growth strategies ultimately convert to ordinary income upon withdrawal, making the account structure, not the return source, the primary driver of taxation.

The Myth of “Dividend Superiority”

Some investment philosophies treat dividend-paying stocks as inherently superior to growth stocks, often citing historical data showing dividend-focused strategies outperforming pure price appreciation. This framing overlooks several important considerations:

- Dividends reduce share price mechanically: When a company pays a $1 dividend, the share price typically drops by approximately $1 on the ex-dividend date. The dividend payment isn’t “free money”, it’s a distribution of company value to shareholders. Total return (dividends plus price appreciation) is what matters, not whether returns arrive as cash or appreciation.

- Dividend sustainability varies: Companies can cut or eliminate dividends during difficult periods. The financial crisis of 2008-2009 saw numerous dividend cuts from previously reliable payers. Treating dividend income as guaranteed or more stable than price appreciation oversimplifies reality.

- Psychological preferences differ from mathematical reality: Many investors prefer receiving regular cash dividends even when selling a small portion of growth holdings would generate equivalent cash flow with potentially different tax treatment. This preference is real and legitimate, but it’s a behavioral preference, not a mathematical advantage.

The key insight is that neither dividends nor capital gains are inherently better. They’re different mechanisms for delivering returns, each with distinct tax characteristics, cash flow patterns, and suitability for different situations.

Why Understanding the Trade-Off Matters

The distinction between dividends and capital gains matters because it affects how investment returns are taxed, accessed, and coordinated across different accounts. Portfolio construction decisions, whether to emphasize dividend-paying stocks, growth-oriented investments, or a mix, depend on income needs, tax considerations, and risk tolerance rather than performance alone.

Account type selection is closely tied to how investment income will be taxed in retirement. Investors who expect meaningful taxable dividend income from brokerage accounts may benefit from Roth retirement accounts, which allow tax-free withdrawals and do not require required minimum distributions for the original owner. This structure can help manage overall taxable income even though dividends themselves do not influence RMD calculations.

Retirement income planning further highlights this trade-off. Choosing whether to rely on taxable dividends, realize capital gains, or withdraw from retirement accounts requires evaluating tax efficiency, cash-flow reliability, and long-term sustainability. Each source of income creates different tax timing and flexibility outcomes.

Estate planning considerations also differ. Under current U.S. tax law, highly appreciated assets held in taxable accounts generally receive a stepped-up basis at death, potentially eliminating unrealized capital gains. Growth-oriented strategies tend to defer more return into appreciation, while dividend-focused strategies distribute more return as taxable income during life, reducing the portion eligible for step-up.

Understanding these differences does not require complex optimization. It requires recognizing that dividends and capital gains create different tax and planning consequences, and that the optimal approach depends on individual circumstances rather than a universal rule.