Why Timing Matters in Tax Strategy (Income, Expenses, and Reality)

13.9 min read

Updated: Jan 8, 2026 - 06:01:56

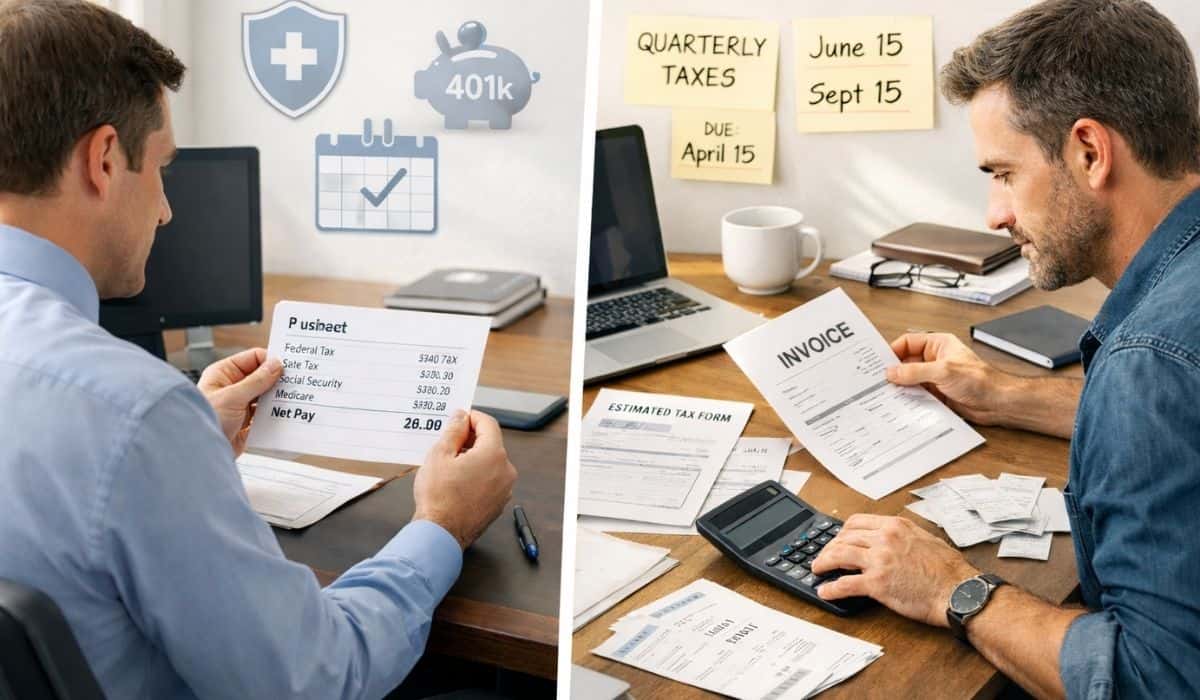

Tax planning isn’t just about what you do, it’s equally about when you do it. Because the U.S. tax system measures income and deductions on an annual basis, shifting the timing of income, expenses, gains, and contributions (within existing rules) can materially change outcomes. The same dollar amount, taxed or deducted in different years, can land in different brackets, interact with phaseouts, trigger or avoid Medicare surcharges, and alter long-term after-tax wealth. Timing is not a loophole; it’s a built-in feature of how taxes are calculated and enforced.

- Income timing drives real differences: Wages and bonuses are taxed when paid, investment gains when realized, and retirement distributions when withdrawn. In some cases, even modest differences in timing can change rates, brackets, or eligibility for income-tested benefits.

- Capital gains are especially timing-sensitive: Holding periods determine whether gains are taxed at ordinary income rates or lower long-term capital gains rates, making patience alone a meaningful tax lever.

- Deductions depend on when you pay: IRA and HSA contributions can be made up to the tax filing deadline, while strategies like bunching medical or charitable expenses can turn otherwise unused deductions into actual tax benefits.

- Retirement timing has compounding effects: Decisions around RMDs, Roth versus traditional contributions, and Roth conversions are fundamentally about when taxes are paid, and those choices can affect brackets, Medicare premiums, and Social Security taxation over time.

- Multi-year planning beats single-year optimization: Coordinating income, deductions, and realizations across years often matters more than the marginal rate in any one year.

Tax strategy discussions often focus on what to do: contribute to retirement accounts, harvest investment losses, maximize deductions. But equally important, and often overlooked, is when to do these things. The tax system largely operates on an annual measurement cycle, which means that decisions about when income is recognized and when deductible expenses are incurred or paid can create material differences in outcomes.

Timing isn’t a loophole or a trick. It’s a structural feature of how tax rules are designed and administered. Understanding timing principles helps you avoid accidental poor decisions and recognize when deliberate, rule-compliant timing choices may better serve your long-term interests.

Income Recognition Versus Cash Received

Most people assume that “income” means money received. For many taxpayers using cash-basis accounting, which includes most employees and many small business owners, this is largely true. But the relationship between cash flow and taxable income is more nuanced than it appears.

Employment Income and Calendar-Year Timing

W-2 wage earners generally recognize income when it is paid, not when it is earned. A December paycheck is taxable in December even if it covers work performed in November. A bonus paid on January 2 is taxable in January, even if it was earned and accrued in December.

This distinction matters most at year-end. Under IRS wage-reporting and constructive receipt rules, employers report wages based on when payment is actually made available to the employee. If a paycheck is issued on January 2 due to a holiday or payroll schedule, that income is reported in January, effectively deferring taxation by a full year.

The same principle applies to bonuses, but with important limits. Companies can time bonus payments only if the employee does not have an unconditional right to receive the bonus before year-end. If a bonus is payable or available in December, it generally cannot be deferred for tax purposes. When deferral is permitted, timing can matter. Someone expecting a significant bonus might benefit from a January payment if they anticipate lower income the following year, such as during a career transition or planned time off. Conversely, accelerating payment into December can make sense if higher income or tax rates are expected next year.

Investment Income and Realization

Investment gains and losses are recognized when realized through a sale or exchange, not when they accrue. A stock purchased for $1,000 that grows to $5,000 generates no taxable income until it is sold. This creates timing flexibility that does not exist with wage income.

The holding period determines how gains are taxed. Assets held for one year or less produce short-term capital gains taxed at ordinary income rates. Assets held for more than one year qualify for long-term capital gains rates of 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on taxable income.

For example, if a gain falls into a 24% ordinary income bracket, selling after 364 days could trigger that rate. Waiting just long enough to cross the one-year threshold could reduce the federal rate to 15%, a difference driven entirely by timing. The investment, gain amount, and economic value are unchanged; only the tax treatment differs.

This creates real planning opportunities. Investors may delay sales to reach long-term status or spread realizations across multiple tax years to avoid concentrating income into a single higher-bracket year.

Retirement Distributions and Required Timing

Retirement account distributions follow specific timing rules that limit flexibility. Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from traditional IRAs and 401(k)s begin at age 73 for individuals born between 1951 and 1959, and at age 75 for those born in 1960 or later. RMDs generally must be taken by December 31 each year, with a one-time exception allowing the first distribution to be delayed until April 1 of the following year.

The timing of these distributions matters because RMDs increase taxable income. This can push retirees into higher tax brackets, trigger Medicare premium surcharges (IRMAA), or increase the taxation of Social Security benefits. Under current IRS rules, the penalty for missing an RMD is 25% of the amount not withdrawn, reduced to 10% if corrected promptly.

Some retirees have flexibility in when during the year distributions are taken. Taking them earlier provides immediate cash flow and allows funds to be used or reinvested sooner. Taking them later keeps assets in tax-deferred accounts longer and delays the tax impact. Neither approach is universally superior; the optimal choice depends on cash-flow needs, multi-year tax planning, and coordination with other income sources.

Expense Timing and Deductibility

Just as income timing matters, so does the timing of deductible expenses. The rules vary based on the type of expense and the taxpayer’s accounting method, and understanding those differences is essential to making legitimate, effective tax decisions.

Above-the-Line Deductions and Annual Limits

Contributions to tax-advantaged accounts are subject to specific timing rules that differ by account type. Employer-sponsored retirement plans such as 401(k) and 403(b) accounts must be funded through payroll withholding, with contribution elections made before compensation is earned and amounts withheld by year-end. Once the final payroll for the year has run, these contributions generally cannot be increased retroactively.

Traditional and Roth IRA contributions follow a different rule. Contributions for a given tax year can be made up until the tax filing deadline, typically April 15 of the following year, and still count for the prior year. This creates a planning window in which someone can evaluate their tax situation after year-end and then decide whether to make an IRA contribution before filing.

Health Savings Account contributions follow the same extended deadline structure. Eligible taxpayers can make HSA contributions up until the tax filing deadline and apply them to the prior year, providing flexibility to optimize adjusted gross income after total income is known.

Annual contribution limits reset each calendar year. For employer-sponsored plans, payroll systems typically prevent contributions once the annual limit is reached. As a result, someone who maxes out their 401(k) earlier in the year generally cannot make additional deferrals later, even if a year-end bonus increases taxable income.

Itemized Deductions and Bunching Strategies

For taxpayers who itemize deductions rather than claiming the standard deduction, timing certain expenses can materially affect tax outcomes. One common approach is “bunching,” where deductible expenses are concentrated into specific years to exceed the standard deduction threshold, while the standard deduction is taken in intervening years.

Medical expenses are deductible only to the extent they exceed 7.5% of adjusted gross income. Taxpayers with recurring but moderate medical costs may never surpass this threshold in a typical year. By intentionally clustering elective procedures, dental work, or other healthcare expenses into a single year, they may exceed the threshold and generate a deduction that would not exist if expenses were spread evenly.

Charitable contributions can be timed in a similar way. Rather than making equal annual donations, a taxpayer near the standard deduction threshold might concentrate contributions into alternate years. In the year with higher giving, itemizing becomes worthwhile; in the other year, the standard deduction applies. The total charitable support remains the same, but the tax benefit improves through timing.

State and local tax deductions can sometimes be managed through timing as well, though the $10,000 State and local taxes (SALT) cap significantly limits this strategy. Prepaying state income taxes in December rather than January may increase deductions in certain cases, but only if the tax has been assessed and the taxpayer has not already reached the SALT limit.

Self-Employment Expenses and Cash-Basis Accounting

Self-employed individuals using cash-basis accounting generally recognize income when it is received and deduct expenses when they are paid. This creates timing flexibility that is not available to W-2 employees.

A consultant who completes work in December may not recognize income until the following year if payment is not made or made available until January. Likewise, business expenses paid in December are deductible in the current year, while the same expenses paid in January become deductions for the next year.

This flexibility is not unlimited. The IRS requires consistent application of accounting methods and applies constructive receipt rules. If income is made available to the taxpayer without substantial restriction, it must generally be reported in that year, even if collection is delayed. However, ordinary business practices involving billing cycles, payment terms, and the timing of discretionary expenses remain legitimate and widely accepted within the tax system.

Why Timing Often Matters More Than Headline Tax Rates

Two people in identical tax brackets can experience very different after-tax outcomes over time purely through timing decisions. The compounding effects of deferral, which brackets income falls into across different years, and the long-term impact of when taxes are paid can matter more than the marginal rate in any single year.

Consider someone who will earn $150,000 this year and $80,000 next year due to a career transition. If they can legitimately defer a $20,000 bonus from December to January, meaning they are not in constructive receipt of that bonus in December and the employer actually pays it in January, they shift that income from being taxed at a 24% marginal rate this year to a 22% marginal rate next year. That is a 2% difference worth $400 on that $20,000.

But the potential benefit can be larger than the $400 implied by the headline bracket change. That same $20,000 landing in the higher-income year might push them over income-based thresholds that reduce or eliminate certain credits, deductions, or other tax benefits. Moving it to the lower-income year not only reduces the marginal rate from 24% to 22%, but can also restore access to benefits that were partially or fully phased out. In those situations, the total tax impact can plausibly exceed $1,000, not because the bracket math changes, but because the income interacts differently with phaseouts and income-tested rules.

Similarly, someone planning major capital gains realizations might split those gains across two years to keep both years’ income below the threshold where the top capital gains rate applies, or below Medicare IRMAA surcharge thresholds, or below other income-tested limits. The same total gain, and the same long-term capital gains treatment, but materially different total tax cost because of how the income stacks into brackets and thresholds across multiple tax years.

Why Timing Decisions Have Long-Term Effects

Tax timing isn’t just about shifting income or deductions between adjacent years. The compounding effects of when taxes are paid can create substantial differences in after-tax outcomes over decades.

Choosing between traditional and Roth retirement accounts is fundamentally a timing decision: pay tax now (Roth) or later (traditional). The advantage depends on the tax rate paid on contributions compared with the effective tax rate paid on withdrawals in retirement. Someone currently in the 12% bracket who expects their retirement withdrawals to be taxed at higher marginal and effective rates may benefit from paying tax now through Roth contributions. Conversely, someone in the 24% bracket today who expects most retirement withdrawals to be taxed at lower effective rates often benefits from traditional contributions that defer tax to a lower-rate period.

The analysis becomes more complex once you account for how retirement income is actually taxed. Withdrawals fill tax brackets progressively, not all at a single rate. Future tax law changes introduce uncertainty. Social Security benefits can become partially taxable as income rises, and Medicare Part B and Part D premiums are tied to income thresholds, creating sharp increases in costs at certain levels. A decision made today based only on current bracket positioning can influence taxes and premiums across decades of retirement.

The timing of Roth conversions, moving money from traditional accounts to Roth accounts and paying tax now, illustrates this complexity. Research and planning guidance show that conversions are most favorable in years when taxable income is temporarily low: after leaving full-time work but before Social Security and required minimum distributions begin, during a sabbatical, following a job loss, or in any year where marginal tax rates are lower than expected in the future.

The same conversion amount executed in different years can produce materially different lifetime outcomes. Converting $50,000 in a year where that income is taxed at 12% results in a $6,000 tax cost. Executing the identical conversion in a 24% marginal-rate year costs $12,000, double the tax for the same long-term Roth benefit.

Common Timing Mistakes and Missed Opportunities

Several timing-related errors appear frequently:

- Year-end scrambling: Waiting until December to think about tax planning leaves limited time and fewer options. Many high-impact timing strategies require advance planning, and late-year decisions are often constrained or suboptimal.

- Ignoring multi-year patterns: Focusing exclusively on the current year’s tax bill can lead to poor decisions when the following year’s situation is known and materially different. Someone retiring in January who takes large retirement distributions in December may pay higher tax because those withdrawals stack on top of a full year of wages.

- Misunderstanding when deadlines actually fall: Assuming all tax decisions must be finalized by December 31 can lead to missed opportunities. While many actions must be completed by year-end, certain contributions, most notably IRA and HSA contributions, can be made up to the tax filing deadline and still count for the prior year.

- Failing to coordinate timing across multiple financial decisions: Planning retirement contributions, income recognition, and investment sales in isolation can reduce their effectiveness. Coordinating timing helps ensure income and deductions fall in years where they provide the greatest relative benefit.

- Not considering state tax timing separately: Most states broadly follow federal timing rules, but differences in rate structures, deductions, and credits can make timing more or less valuable at the state level than at the federal level.

How Timing Connects to Other Strategic Decisions

Timing doesn’t exist in isolation; it interacts with nearly every other aspect of tax strategy and financial planning:

Investment tax-loss harvesting is primarily a timing strategy. It accelerates the recognition of losses to offset current-year gains (and limited ordinary income), while attempting to maintain similar market exposure, assuming wash-sale rules are avoided.

Charitable giving through donor-advised funds allows donors to claim a deduction in the current year while distributing funds to charities over multiple future years, separating the tax deduction decision from the actual grant timeline.

Retirement account contribution timing affects not just the current year’s AGI but also eligibility for credits and deductions that use AGI as a threshold, primarily for pre-tax or deductible contributions, not Roth contributions.

Business expense timing for self-employed individuals affects current-year taxable income and cash flow, which in turn influences how much needs to be paid during the year to meet estimated tax safe-harbor rules and avoid underpayment penalties.

The Principle Underlying All Timing Decisions

The core insight about timing is that taxation is not a one-time event but a repeated annual process that interacts with financial decisions made throughout life. When viewed over multiple years, seemingly small timing choices—when to realize gains, when to take deductions, when to recognize income—can compound into meaningful differences in after-tax wealth.

This does not mean obsessing over minor optimizations or structuring decisions solely around taxes. It means recognizing that when flexibility exists around the timing of financial events, understanding the tax consequences of different options leads to better-informed choices.

The goal is not to minimize any single year’s tax bill. It is to optimize lifetime after-tax outcomes by deciding when to pay tax versus defer it, when to recognize income or losses, and when to take deductions in a way that aligns with overall circumstances across multiple years.