Taxable Income vs Adjusted Gross Income (AGI): What Actually Drives Tax Outcomes

12.8 min read

Updated: Jan 8, 2026 - 02:01:24

The U.S. tax system does not rely on a single income number. Instead, Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) and taxable income play very different roles. Taxable income determines how much federal income tax you owe, but AGI often acts as a strategic gatekeeper that can affect eligibility for deductions, credits, contribution limits, subsidies, and phaseouts. Many tax benefits can be reduced or preserved based on changes in AGI, not just on your final tax bill. Understanding how income flows from total income to AGI and then to taxable income can help with tax, retirement, investment, and health insurance planning.

- AGI is calculated before the standard or itemized deduction and is reduced by above-the-line adjustments like traditional retirement contributions, HSA contributions, student loan interest, and self-employment deductions.

- Most income-based tax benefits key off AGI or modified AGI, including Roth IRA eligibility, IRA deductibility, Child Tax Credit phaseouts, student loan interest deductions, ACA premium subsidies, and Medicare IRMAA surcharges.

- Taxable income determines your tax bill, but two taxpayers with the same AGI can owe very different amounts depending on whether they take the standard deduction or itemize.

- Small AGI reductions can meaningfully affect eligibility, such as helping restore Roth IRA eligibility or full IRA deductibility, depending on the applicable rules.

- Gross income alone is misleading; how income is adjusted and deducted often matters more than salary or headline earnings when evaluating after-tax outcomes.

Most people think of income as a single number, the total they earn from work, investments, and other sources. In reality, the U.S. tax system does not rely on one income figure. Instead, it uses several different income measures, each designed for a specific role in calculating taxes and determining eligibility for deductions, credits, and other tax benefits.

Two figures matter more than any others: Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) and taxable income. While taxable income determines how much federal income tax you ultimately owe, AGI plays a broader strategic role throughout the tax code.

Understanding the difference between AGI and taxable income, and why AGI functions as a gatekeeper for so many tax benefits, can help inform financial decisions that affect after-tax outcomes. Many deductions, credits, contribution limits, and phaseouts are based on AGI, not on the final amount of income that is actually taxed.

How Income Flows Through the Tax Return

The path from income to final tax owed follows a defined sequence, with each step serving a distinct purpose under IRS Form 1040. You begin with total income, which represents the combined amount of all taxable income sources reported on the return, including wages, self-employment income, interest, dividends, capital gains, retirement distributions, and other taxable income items. This figure does not include non-taxable items such as tax-exempt interest.

From total income, you subtract above-the-line deductions, also known as adjustments to income. These include deductible traditional IRA contributions, student loan interest, the deductible portion of self-employment tax, health savings account contributions, and several other specific adjustments. After these deductions, the result is Adjusted Gross Income (AGI).

From AGI, you subtract either the standard deduction or itemized deductions, whichever is higher. For the 2024 tax year, the standard deduction is $14,600 for single filers and $29,200 for married couples filing jointly. After this subtraction, the remaining amount is taxable income, which is used to calculate federal income tax through the progressive tax bracket system.

This sequence matters because AGI acts as a gatekeeper for many credits, deductions, and phaseouts, while taxable income determines how much tax is actually owed.

What Adjusted Gross Income Actually Is

Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) is not simply your salary or wages. It is a calculated tax figure that starts with your total income from all sources and then subtracts specific IRS-approved adjustments, before either the standard deduction or itemized deductions are applied.

Total income includes wages, self-employment earnings, interest, dividends, capital gains, retirement distributions, and other taxable income. From this amount, certain adjustments, commonly called above-the-line deductions, are subtracted to arrive at AGI.

Common adjustments that reduce total income to AGI include:

- Traditional IRA contributions (subject to annual limits and income restrictions if covered by a workplace retirement plan)

- Student loan interest paid (up to $2,500, subject to income phaseouts)

- The deductible portion of self-employment tax (one-half of the total)

- Health Savings Account (HSA) contributions

- Self-employed health insurance premiums

- Certain educator expenses

- Moving expenses for active-duty military members

- Alimony paid under divorce agreements finalized before 2019

These above-the-line deductions apply before AGI is calculated on the federal tax return and are available whether you itemize deductions or claim the standard deduction. This makes them valuable because they reduce income at an early stage of the tax calculation.

AGI is reported to the IRS each tax year and functions as a key control point in the tax system. It determines eligibility for many deductions, credits, and income-based phaseouts, and it is commonly used, sometimes with state-specific modifications, as the starting figure for calculating state income taxes.

Why AGI Functions as a Gatekeeper

Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) functions as a gatekeeper in the tax system because eligibility for many credits, deductions, and benefits is determined using AGI or a related modified AGI (MAGI) calculation. As income rises, these benefits often phase out gradually or disappear entirely, making AGI important for planning purposes beyond gross income or even taxable income.

Several major tax provisions rely on AGI or MAGI thresholds:

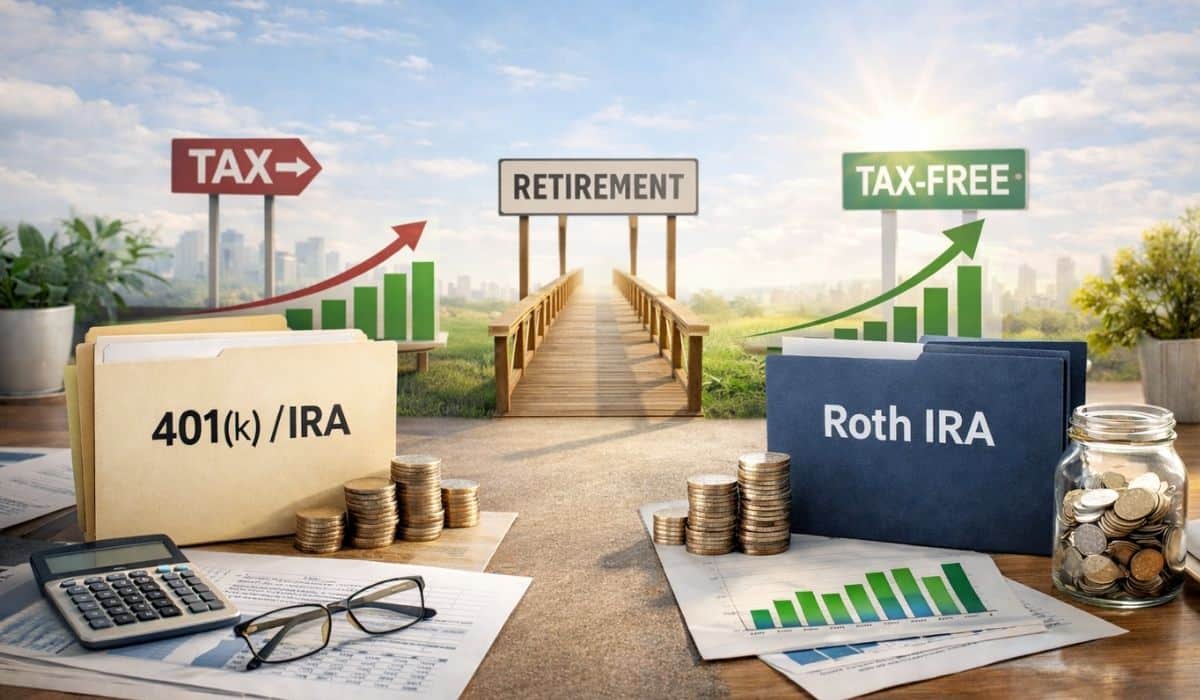

- Roth IRA contribution eligibility is based on modified AGI, which starts with AGI and adds back certain excluded items defined by the IRS. For 2024, single filers begin seeing reduced contribution limits at $146,000 MAGI and lose eligibility entirely at $161,000 MAGI.

- The Child Tax Credit begins phasing out once income exceeds $200,000 for single filers and $400,000 for married couples filing jointly. While often described using AGI, the phaseout is effectively tied to modified AGI, which for many taxpayers is the same as AGI.

- The student loan interest deduction phases out for single filers in 2024 when modified AGI falls between $80,000 and $95,000, with no deduction allowed above that range.

- Traditional IRA deduction eligibility, when a taxpayer is covered by a workplace retirement plan, also depends on modified AGI. For 2024, the deduction phases out for single filers between $77,000 and $87,000 MAGI.

- Premium tax credits for health insurance purchased through the ACA marketplace are calculated using an ACA-specific version of modified AGI and depend on household income relative to the federal poverty level.

The pattern is consistent: access to many tax benefits is determined by AGI or MAGI, not by gross income or taxable income. As a result, strategies that reduce AGI can provide value beyond immediate tax savings by helping preserve eligibility for income-based credits, deductions, and subsidies.

How AGI Differs From Taxable Income

While AGI determines eligibility for many tax provisions, taxable income determines which tax brackets apply and how much federal income tax you actually owe. This distinction explains why two taxpayers with identical AGI can end up with very different tax bills.

Consider two single filers, each with $80,000 in AGI:

-

Person A takes the standard deduction of $14,600, resulting in $65,400 of taxable income.

-

Person B itemizes deductions, mortgage interest, state and local taxes (subject to the $10,000 SALT cap), and charitable contributions, totaling $22,000, resulting in $58,000 of taxable income.

Both taxpayers have the same AGI, meaning they face the same income-based eligibility rules for credits, deductions, and other benefits. However, Person B owes less federal income tax because their taxable income is lower.

The $7,400 reduction in taxable income lowers Person B’s tax bill by approximately $1,600, assuming those dollars would otherwise be taxed at a 22% marginal rate. The exact savings depend on how income is distributed across tax brackets, but the directional effect is the same.

This illustrates why the sequence matters: AGI determines what you’re eligible for. Taxable income determines what you pay.

Why Understanding AGI Matters for Planning

Because AGI determines eligibility for so many tax provisions, reducing AGI, even by relatively small amounts, can affect benefits that may be more valuable than the immediate tax savings from the adjustment itself.

Consider a single filer earning $147,000 of modified AGI in 2024 who wants to contribute to a Roth IRA. They are $1,000 above the phaseout threshold that begins at $146,000 MAGI. Increasing a traditional 401(k) contribution by $1,000 reduces both AGI and MAGI by $1,000, bringing income below the phaseout threshold and potentially restoring full Roth IRA contribution eligibility.

The immediate tax value of that $1,000 contribution is approximately $240, assuming a 24% marginal tax rate. But the restored Roth eligibility may also be valuable: the ability to contribute up to the $7,000 Roth IRA limit for 2024, allowing those funds to grow tax-free over time. In this case, the AGI impact may matter beyond the deduction itself.

A similar dynamic applies to traditional IRA deductibility. A single filer covered by a workplace retirement plan with $78,000 of AGI sits within the 2024 phaseout range for traditional IRA deductions. Increasing their 401(k) contribution by $2,000 reduces AGI to $76,000, moving them below the phaseout range and potentially restoring full deductibility of a traditional IRA contribution. The same AGI reduction both lowers current tax exposure and may unlock another deductible opportunity.

These dynamics explain why effective tax planning often focuses on AGI management rather than simply reducing taxable income. Taxable income determines tax owed, but AGI determines which planning opportunities are available.

Common Misunderstandings About Income Measures

Several persistent misconceptions create confusion about how income figures work:

- “My income is my salary.” Your salary is only one component of total income. Wages, investment income, capital gains, retirement distributions, interest, dividends, and other sources all contribute to the income figures used in the tax system.

- “A higher AGI means higher taxes.” Not necessarily. AGI does not directly determine how much tax you owe, taxable income does. AGI primarily acts as an eligibility gatekeeper for deductions, credits, and other provisions. In some cases, someone with a higher AGI but large itemized deductions may owe less tax than someone with a lower AGI who takes the standard deduction.

- “Deductions reduce my income. Not all deductions work the same way. Above-the-line deductions reduce AGI. Standard and itemized deductions reduce taxable income. Because they apply at different stages of the calculation, they can affect tax outcomes in very different ways.

- “Modified AGI is the same as AGI.” Many tax provisions use modified AGI (MAGI), which starts with AGI and then adds back specific items defined by that provision, such as excluded foreign income or tax-exempt interest. The required add-backs vary by rule, meaning there is no single universal MAGI and a taxpayer may have multiple MAGI calculations for different purposes.

How AGI Connects to Investment and Retirement Decisions

Understanding AGI’s role clarifies why certain account types and contribution strategies matter beyond immediate tax savings. Traditional retirement account contributions (401(k), 403(b), traditional IRA if eligible) reduce AGI directly. This affects both current-year tax and eligibility for other benefits. Roth contributions don’t reduce AGI, which means they may preserve eligibility for income-tested benefits in the current year but provide tax-free growth and withdrawals later.

Health Savings Account contributions reduce AGI while providing triple tax benefits: deductible contribution, tax-free growth, and tax-free withdrawals for qualified medical expenses. For those eligible (requires enrollment in a high-deductible health plan), HSAs are among the most tax-efficient savings vehicles available.

Capital gains timing affects AGI because realized gains increase it. Someone near a phaseout threshold might delay selling appreciated investments to avoid pushing AGI above the limit in the current year, even if the long-term capital gains rate itself doesn’t change.

Self-employment income affects AGI both directly (through net self-employment earnings) and indirectly (through the self-employment tax deduction, which reduces AGI by one-half of self-employment tax paid). This creates planning opportunities around income and expense timing that don’t exist for W-2 wage earners.

How AGI Interacts With Other Financial Decisions

AGI impacts areas beyond traditional tax planning. Health insurance subsidies through ACA marketplaces are calculated based on household income as a percentage of the federal poverty level, using an ACA-specific modified AGI definition. For households near key income thresholds, managing AGI through retirement contributions or other allowable adjustments can materially affect health insurance premiums. Although recent legislation temporarily removed strict subsidy cliffs through 2025 under then-current law, subsidy amounts still phase down as income rises and rules can change.

Medicare premiums for Part B and Part D use modified AGI from two years prior to determine whether higher earners owe Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amounts (IRMAA). For 2024, IRMAA surcharges begin above $103,000 of MAGI for single filers. Because these determinations look back in time and are recalculated annually, managing AGI in the years leading up to Medicare enrollment can help reduce the likelihood of higher premiums in future Medicare years.

College financial aid calculations also begin with AGI. The FAFSA form pulls AGI directly from IRS data and then applies its own adjustments to determine aid eligibility. While manipulating income solely to qualify for aid is neither ethical nor advisable, understanding how AGI feeds into the formula helps families plan legitimate financial decisions around college timing and funding.

Many state tax systems start with federal AGI and then apply state-specific additions and subtractions. As a result, reducing federal AGI often reduces state taxable income as well, multiplying the overall benefit of income-planning strategies.

Taxable Income’s Role in the Final Calculation

While AGI determines eligibility for many tax benefits, taxable income determines the actual tax bill. This is where the choice between the standard deduction and itemized deductions becomes decisive.

For 2024, most single filers take the $14,600 standard deduction, largely because the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act significantly increased the standard deduction, making itemizing less beneficial unless deductible expenses exceed that amount. Many taxpayers’ itemizable expenses, such as mortgage interest, state and local taxes, and charitable contributions, simply do not clear that threshold.

The $10,000 cap on state and local tax (SALT) deductions, enacted in 2017 and subject to future law changes, reduced the value of itemizing for many taxpayers. Someone paying $15,000 in combined state income and property taxes can deduct only $10,000, meaning substantial mortgage interest and charitable contributions are required before itemizing exceeds the standard deduction.

As a result, strategies focused solely on increasing itemized deductions may not change tax outcomes at all if the total remains below the standard deduction. Understanding this distinction helps avoid tax-motivated spending decisions that provide no actual tax benefit.

Why This Matters More Than Gross Income

Gross income figures, salary, total compensation, and household earnings, dominate most personal finance discussions. However, gross income alone does not determine tax liability or eligibility for many tax benefits.

Consider two single filers in the 2024 tax year. One earns $100,000 but claims $15,000 in above-the-line adjustments and $20,000 in itemized deductions, resulting in $65,000 of taxable income. Another earns $80,000, claims no adjustments, and takes the $14,600 standard deduction, leaving $65,400 of taxable income. Despite the large difference in gross earnings, their taxable income levels are nearly identical.

While the first individual earns significantly more, the two taxpayers may face similar federal income tax liability because tax brackets apply to taxable income, not gross income. However, their adjusted gross income differs meaningfully, $85,000 versus $80,000, which can affect eligibility for income-based credits, deductions, and benefits that phase out at specific AGI thresholds.

This illustrates why broad assumptions based solely on income levels often fail. Tax outcomes depend on how income is structured, which adjustments apply, and whether itemized deductions exceed the standard deduction. Gross earnings alone rarely provide enough information to evaluate tax strategy or financial eligibility accurately.