The Niche Report – The Space Illusion: How Billionaire Ambition Masks the Real Money Being Made in Orbit

8.9 min read

Updated: Dec 20, 2025 - 08:12:20

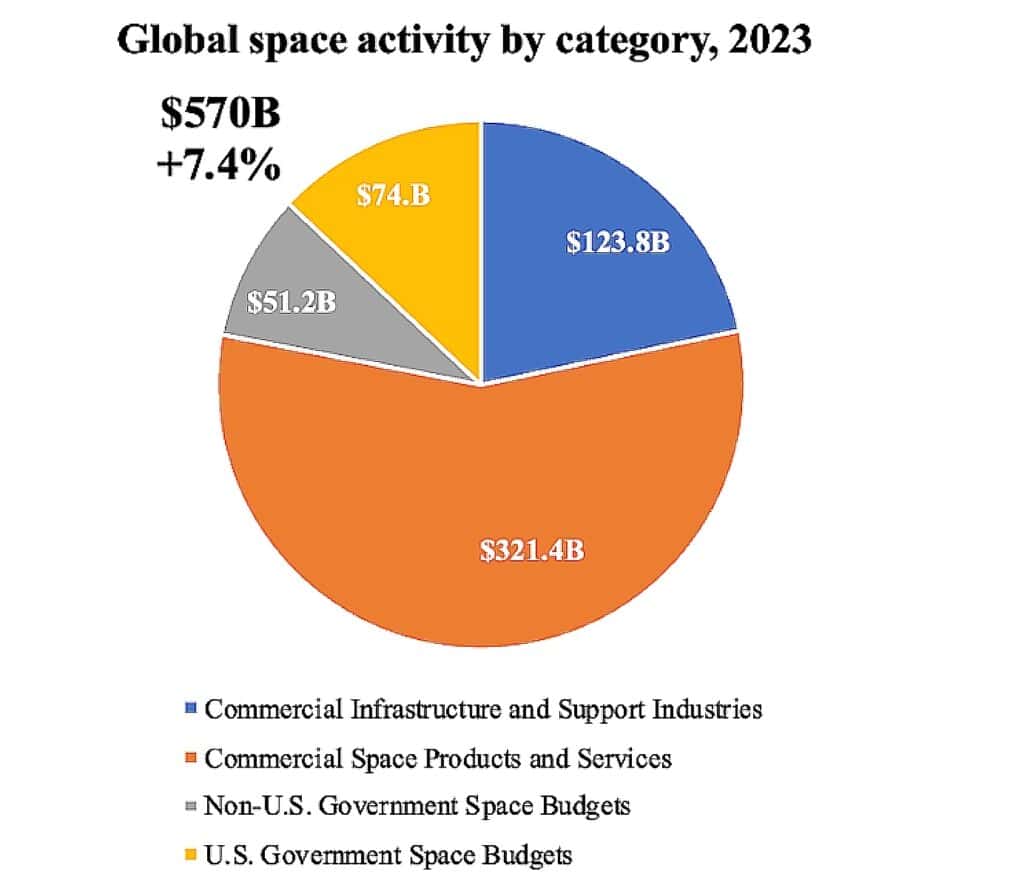

The modern space economy topped roughly US$570B in 2023, but only a small slice comes from rockets, tourism, or billionaire-led ventures. Most revenue grows quietly in satellite services, broadband, navigation, Earth-observation analytics, and ground-station infrastructure. SpaceX is the only billionaire-backed firm approaching a mature revenue model, driven by Starlink’s positive cash flow, while Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic remain either government-funded or structurally unprofitable. For retail investors, the investable parts of space are still the workhorse operators, Planet Labs, Rocket Lab, and diversified aerospace ETFs, not the headline-grabbing rockets.

- The global space economy hit ~US$570B in 2023, with ~80% from commercial markets, not launches.

- Satellite services and manufacturing drive the largest revenue share, according to the Satellite Industry Association and BryceTech.

- SpaceX generated about US$8.7B in 2023 revenue and projects ~US$15.5B for 2025, powered by Starlink’s first year of positive net cash flow.

- Blue Origin relies heavily on founder funding and NASA contracts, while Virgin Galactic posted only ~US$7M revenue against a ~US$347M loss in 2024.

- Public plays like Rocket Lab (US$436.2M in 2024 revenue) and Planet Labs (US$220.7M in FY2024) offer retail access but remain unprofitable; ETFs provide broader diversification.

If you judged the “space business” purely by media coverage, it would appear to revolve around three high-profile billionaires, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson, whose companies dominate headlines with rocket launches, capsule tests and suborbital tourism flights. This framing fuels the impression of a modern space race built on dramatic visuals and extremely expensive trips to the edge of space.

But step away from the launch-pad glamour and the picture becomes more complex. Companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic attract disproportionate attention because rockets make for compelling media, not because they represent the bulk of the space economy. In reality, most of the global space industry is driven by far less sensational segments such as satellite manufacturing, communications, Earth-observation services, navigation systems and ground-station infrastructure.

That distinction raises an important question: how much of the billionaire-led activity is a conventional, revenue-generating business, and how much is long-term experimentation funded by deep pockets? And beyond the headlines, where is the actual money in the space sector being made today, and is any of it realistically accessible to ordinary investors?

The Space Economy Is Big — but Not Where You Think

Start with the scale. The global space economy reached about US$570 billion in 2023, according to the Space Report 2024 Q2 from the Space Foundation. That represents a 7.4% increase from the prior year, and roughly 80% of total activity came from commercial markets rather than government spending.

Source: Space Foundation

When you drill down, the picture becomes even more revealing. Industry assessments consistently show that satellite-related markets, communications, navigation, Earth observation, broadband services, and ground infrastructure, dominate global space-economy revenues. These segments form the backbone of the industry, generating far more value than rockets or tourism.

The Satellite Industry Association’s annual overview, compiled with BryceTech, highlights that satellite services and related downstream applications represent the largest share of the global space economy. While the full 2024 dataset is not publicly released, summaries confirm that satellites remain the sector’s economic engine.

By comparison, launch services account for only a small percentage of global space revenue. Public summaries of major reports show that rockets contribute a single-digit share of the total, reinforcing how tiny the launch business is relative to satellite manufacturing and services.

In other words, most of what we call the “space business” is not Mars colonies, space tourism, or dramatic booster landings. It is the unglamorous but essential infrastructure of global connectivity: satellite broadband, GPS, weather systems, television distribution, Earth-observation analytics, and worldwide communication networks.

Against that backdrop, the real question becomes clear: how do billionaire-led rocket companies compare to the sectors that generate the bulk of space-economy value?

SpaceX: From Near-Death to a Real Business

Of the three marquee names in the modern space sector, SpaceX remains the closest thing to a conventional, though still highly ambitious, business success story. Industry estimates indicate that SpaceX generated roughly US$8.7 billion in revenue in 2023, reflecting strong demand across commercial launches, government missions and rapidly expanding satellite-internet services.

In 2025, the company’s founder projected that SpaceX could reach about US$15.5 billion in annual revenue, combining Starlink subscriptions, Falcon 9 launch activity, and new enterprise connectivity offerings. This growth trajectory continues to position SpaceX as the largest privately held aerospace company in history.

A major driver of this momentum is Starlink, the company’s global low-Earth-orbit broadband network. SpaceX has stated that Starlink recently completed its first full year of positive net cash flow, a milestone that underscores rising subscriber numbers and improving unit economics across residential, mobility, maritime and government markets.

Yet even with this progress, SpaceX’s financial profile sits on a razor-thin line between operational profitability and continuous reinvestment. Publicly available disclosures show that a significant portion of the company’s budget flows directly into Starship, the fully reusable heavy-lift rocket system designed for deep-space missions, lunar transport and high-capacity satellite deployment. Development cycles remain extremely costly, and each test campaign requires substantial capital.

Viewed strictly through an investment lens, SpaceX resembles a hybrid model: stable, recurring revenue from Starlink and Falcon 9 launch services, paired with a long-dated, high-risk capital commitment to next-generation heavy-lift capabilities and deep-space ambitions. It is a company with remarkable revenue momentum, but one that continues to channel much of its earnings into its most speculative, and most transformative, future technologies.

Blue Origin: Slowly Evolving From Hobby Rocket to Contractor

Blue Origin, founded by Jeff Bezos, has long been viewed as the most “hobby-like” space venture: privately funded, quiet, and lacking visible financials. That image is starting to shift.

In 2023, the company’s national team secured a US$3.4 billion NASA contract to develop a lunar lander for the Artemis V mission. It remains Blue Origin’s largest government win and a major step toward becoming a serious contractor.

In 2025, Blue Origin successfully launched its heavy-lift New Glenn rocket, carrying NASA science payloads and demonstrating real launch capability after years of delays. The milestone signals Blue Origin’s entry into competitive launch services rather than purely development work.

Still, the company remains privately held with limited disclosure. Its business relies heavily on founder funding and large government awards rather than diversified, recurring revenue streams, making it harder to treat as a fully mature commercial launch provider.

Virgin Galactic: The Poster Child For Vanity Economics

Virgin Galactic, Richard Branson’s sub-orbital tourism venture, remains one of the most speculative plays in the modern space market. The company’s flagship offering, sub-orbital space tourism flights, has been marketed at US$450,000 to US$600,000 per seat.

Financial performance reinforces the challenge. In 2024, the company reported about US$7 million in revenue and a net loss of roughly US$347 million, based on figures disclosed in its 2024 financial results.

With limited flight frequency, extremely high operating expenses, and a narrow base of ultra-wealthy customers, Virgin Galactic continues to look more like a high-cost, high-risk aspiration than a scalable space-tourism business model.

The Quiet Businesses of Space: Satellites, Data and Workhorse Rockets

While billionaire-owned rockets dominate the headlines, the most reliable money in the space sector still comes from far less glamorous operations.

The satellite industry remains the core economic engine. According to the 2024 State of the Satellite Industry Report compiled by the Satellite Industry Association (SIA) and BryceTech, satellite services, manufacturing, ground equipment and launch generated roughly US$293 billion. This dwarfs revenue from space tourism or deep-space ventures and underscores how commercial satellite markets drive the majority of sector activity.

Planet Labs offers a clear example of this steady business model. The company, which provides Earth-imaging data and analytics, reported US$220.7 million in revenue for its fiscal year 2024, a 15% year-over-year increase. It also surpassed 1,000 customers, most of them government agencies or private enterprises relying on recurring data streams.

Rocket Lab, another workhorse of the commercial space economy, also had a record performance. In 2024, the company generated US$436.2 million in revenue, up 78% from the previous year, supported by a strong cadence of Electron launches and expanding space-systems contracts for satellite components and spacecraft.

Despite their scale, both Planet Labs and Rocket Lab remain unprofitable on a net basis, largely due to high capital expenditure and ongoing R&D. Even so, their recurring revenue and diversified B2B service models demonstrate how the space sector is quietly maturing, built less on hype and more on stable contracts, data products and dependable launch demand.

Can Retail Investors Sensibly Invest in Space?

For a broad personal-finance audience like Mooloo Money’s, the investability question matters as much as the technology. Today, retail investors effectively face three layers of space-sector exposure.

- Public pure-play stocks such as Rocket Lab and Planet Labs offer the most direct route into the commercial space economy. Both companies are growing quickly but still report net losses, which means their share prices stay volatile and driven more by long-term growth expectations than predictable cash flow.

- Private giants like SpaceX and Blue Origin remain largely out of reach for typical investors. Because they are not publicly traded, access usually comes only through specialised private funds or secondary-market vehicles aimed at accredited investors, often at valuations that price in future growth rather than current earnings.

- Diversified exposure through broader aerospace or space-thematic funds offers a more balanced approach. These ETFs blend satellite operators, launch providers, defense contractors and tech firms, reducing single-stock risk.

In short, for most retail investors, space investing remains a speculative satellite allocation, a small, high-potential slice rather than a core portfolio holding.

Vanity Project or Real Infrastructure? The Truth Is Both

If you judged the “space business” solely through media coverage, you would think it revolves almost entirely around three billionaires, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson, whose rockets, capsules and tourism flights dominate headlines. This framing creates the sense of a modern space race defined by dramatic visuals and ultra-expensive trips to the edge of space.

But step away from the spectacle, and the real picture looks very different. Companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic attract disproportionate attention because rockets make for compelling television, not because they generate most of the revenue. In reality, the bulk of the global space economy is powered by far less glamorous segments: satellite manufacturing, communications, Earth-observation data, navigation systems, broadband infrastructure and ground-station networks.

That contrast naturally leads to a deeper question: how much of the billionaire-led activity is genuine, recurring revenue, and how much is long-horizon experimentation sustained by deep pockets? More importantly, where is the real money being made today, and how much of it is accessible to everyday investors?