Airlines vs. Hotels: Which Is The WORST Investment?

6.5 min read

Updated: Dec 20, 2025 - 08:12:56

Airlines and hotels both tempt investors with global travel growth, but history shows they’ve destroyed more shareholder value than they’ve created. Airlines remain capital-heavy, low-margin, and shock-sensitive, while leading hotel chains like Marriott and Hilton have shifted to asset-light, fee-based models that provide more stable returns. The key: understand where the profits truly flow in the travel ecosystem.

- Airlines remain wealth traps: According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), global carriers earn net margins of only 2–4% in good years, well below their cost of capital, making the industry chronically unprofitable.

- Hotels face similar cyclicality but smarter structures: Property-heavy hotel REITs remain risky, yet franchisors like Marriott and Hyatt collect stable management fees without owning real estate.

- Asset-light wins: The pandemic proved that hotel brands with fee-based income models weather downturns better than capital-intensive airlines or hotel property owners.

- Better travel exposure: Investors may find stronger economics in adjacent plays like Visa, Mastercard, or Booking Holdings, which benefit from global travel spending without owning planes or hotels.

- Bottom line: Airlines face structural headwinds, volatile fuel costs, limited pricing power, and high fixed expenses, while hotel franchisors now resemble scalable service brands with more resilient profit streams.

When it comes to travel and hospitality stocks, investors often dream of cashing in on humanity’s endless desire to explore the world. But here’s the uncomfortable truth: both airlines and hotels have destroyed more shareholder value over the decades than they’ve created. Airlines have long been plagued by bankruptcies, high costs, and relentless competition, making consistent profitability nearly impossible. Hotels, while slightly more stable, face cyclical demand, heavy debt, and constant pressure on margins. If you’re choosing between these two sectors, you’re essentially deciding between getting punched in the face or kicked in the stomach.

The Case Against Airlines: A Century of Wealth Destruction

Warren Buffett, who once owned stakes in major U.S. carriers before selling them during the COVID-19 pandemic, has long been skeptical of airline investments, and with good reason. The airline industry has historically been a graveyard for shareholder wealth.

Airlines operate as commodity businesses. When booking a flight from New York to Los Angeles, most travelers care about price and schedule, not brand. This weak differentiation limits pricing power and fuels constant fare wars, good for consumers, bad for profits.

The numbers tell the story. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), global airlines typically earn net margins of just 2–4% even in good years, well below their cost of capital. The sector remains highly sensitive to external shocks: recessions slash business travel, fuel price spikes raise costs, and crises like 9/11 or the pandemic trigger sudden collapses in demand.

Capital intensity magnifies the problem. Airlines must invest billions in aircraft and maintenance, and labor, fixed costs that persist even when planes fly half-empty. This structural burden has led to repeated bankruptcies and shareholder wipeouts, from Pan Am and TWA to Eastern Airlines and beyond.

The COVID-19 crisis exposed these weaknesses dramatically. Within weeks of global travel restrictions, carriers needed massive government bailouts to stay afloat. Despite cyclical rebounds, the industry’s underlying economics remain fragile, an enduring example of how growth and glamour can coexist with chronic value destruction.

The Case Against Hotels: Cyclical Pain With a Real Estate Twist

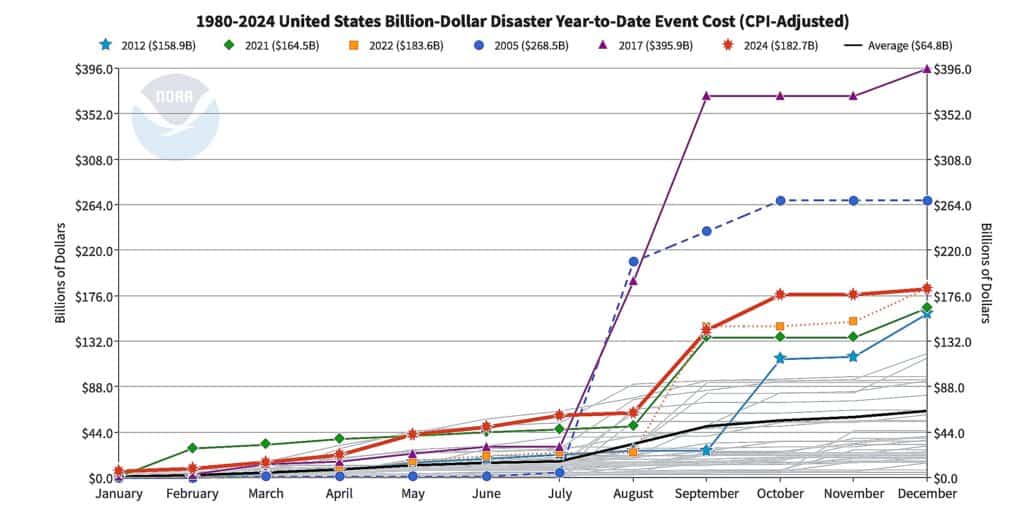

Hotels share many challenges with airlines. They’re intensely cyclical, capital-intensive, and vulnerable to external shocks. A recession reduces both business and leisure travel. Geopolitical instability keeps tourists home. Even local events like natural disasters can devastate occupancy rates at specific properties.

Source: NCEI

The fixed costs are equally punishing. A hotel must maintain its property, staff its operations, and cover financing costs regardless of occupancy levels. Unlike airlines that can reduce capacity, hotels can’t easily close portions of their properties. Property taxes and maintenance continue no matter how many rooms sit empty, and baseline staffing requirements limit flexibility during downturns.

Hotel REITs that own these properties face added real estate risks. Property values often fall during economic downturns, and leveraged owners can face distress when occupancy drops. The 2008 financial crisis caused widespread write-downs across the hospitality sector, while COVID-19 delivered another severe blow, especially to urban business hotels dependent on corporate travel.

The Critical Difference: Asset-Light vs. Asset-Heavy

Here’s where the comparison becomes more nuanced. While airlines continue to operate with heavy capital requirements, major hotel companies have spent the past two decades transforming their business models. Industry leaders like Marriott, Hilton, and Hyatt have shifted toward “asset-light” strategies that fundamentally reshape their risk profiles.

Rather than owning hotels outright, these companies primarily franchise their brands or manage properties owned by third parties. The hotel owners bear the costs of real estate, property maintenance, and occupancy risk, while the franchisors collect management and franchise fees. This shift has dramatically reduced capital intensity, stabilized cash flows, and improved operating margins. In essence, these global chains now operate more like brand-licensing and management businesses than traditional property owners.

The advantages became clear during the COVID-19 pandemic. Property owners suffered steep losses as travel collapsed, yet the major franchisors remained more resilient because their fee-based models provided recurring revenue even amid declining occupancy. This structure doesn’t eliminate risk entirely but does provide meaningful insulation from real estate downturns.

Hotel chains also benefit from brand and location-based pricing power that airlines rarely achieve. A luxury property in Paris or New York can command premium rates based on service quality and brand reputation. Airlines, by contrast, operate in a more commoditized environment where identical routes are primarily differentiated by price and schedule. That makes the hotel sector’s asset-light evolution a striking contrast to the airline industry’s capital-heavy, price-sensitive model.

The Verdict: Airlines Face Greater Structural Challenges

When comparing the two sectors, airlines present deeper and more persistent structural challenges. The business model operates on thin margins, requires massive capital investment, and is highly sensitive to economic cycles, fuel prices, and geopolitical events. The industry’s long record of poor returns reflects not temporary setbacks but enduring economic constraints.

By contrast, major hotel franchisors such as Marriott and Hilton have transformed their models over the past two decades. Through asset-light strategies, they primarily franchise and manage properties owned by others, earning fees while avoiding most real estate and capital risks. This approach produces steadier cash flows and greater resilience, even though the industry remains cyclical and was severely tested during COVID-19.

Still, the distinction matters. Hotel REITs and property-owning companies face fundamentally different risks. They remain leveraged real estate businesses exposed to interest rate shifts, property value declines, and downturns in travel demand. When compared to airlines, these asset-heavy hotel owners share a closer risk profile, with high fixed costs and vulnerability to economic shocks.

A Better Alternative: Consider Adjacent Opportunities

For many investors, avoiding both airlines and hotels may be the smarter choice. The broader stock market offers diverse industries with stronger economics and less capital intensity.

Those seeking exposure to travel growth can consider companies that benefit indirectly. Payment processors like Visa and Mastercard earn fees from global travel spending without owning planes or hotel properties. Online travel agencies such as Booking Holdings and Expedia Group aggregate demand, collect commissions, and operate asset-light models with scalable economics.

For investors choosing direct exposure, careful research is essential. Both sectors demand understanding of unique metrics, airlines track load factors and fuel costs, while hotels rely on occupancy and RevPAR. The travel industry continues expanding as global wealth rises, but that growth doesn’t guarantee superior shareholder returns. Capital intensity, competition, and cyclical swings remain persistent risks.

Between the two, airlines face deeper structural headwinds, high fixed costs, volatile fuel prices, and limited pricing power. Still, for most portfolios, maintaining minimal exposure to both may be the most prudent long-term approach.