Why the 50 / 30 / 20 Budget Doesn’t Work for Most People

4.9 min read

Updated: Dec 21, 2025 - 11:12:12

The 50/30/20 budget rule, 50% to needs, 30% to wants, 20% to savings and debt, remains popular for its simplicity, but today’s household budgets show why it rarely works in practice. Rising housing and healthcare costs, high debt loads, and irregular incomes make the rule unrealistic for many U.S. families. While it can still serve as a loose guideline for stable, low-debt households, flexible budgeting models are more effective in 2024–2025.

- Housing & healthcare costs: BLS data shows rent and medical expenses often push “needs” above 50% of income, especially in high-cost cities.

- Debt pressures: Federal Reserve reports many households use the entire 20%, or more, just for debt, leaving no room for savings.

- Income volatility: Freelancers and gig workers with fluctuating pay find fixed percentages unworkable month to month.

- Blurred categories: Essentials like internet and smartphones blur the line between “wants” and “needs,” weakening the rule’s clarity.

- Better alternatives: Options like 70/20/10, zero-based budgeting, or needs-first budgeting offer more flexibility and realism.

The 50/30/20 budget rule has been one of the most widely cited personal finance frameworks for nearly two decades. Its simplicity, 50% of income to needs, 30% to wants, and 20% to savings and debt repayment, makes it appealing as an easy-to-remember formula. Popularized by Senator Elizabeth Warren in her book All Your Worth, the rule still appears in financial blogs, advice columns, and money apps. However, when examined against the reality of household budgets, it becomes clear why this model doesn’t fit the majority of American families today.

Why the 50/30/20 Rule Fails in Practice

Spending Patterns Don’t Match the Model

Federal Reserve data shows that household spending rarely aligns with the neat percentages the rule prescribes. For middle-income families, essentials often exceed 50% of income, leaving little room for wants or consistent savings. For low-income households, the imbalance is even greater, necessities such as food, utilities, and rent can eat up nearly the entire paycheck. On the other end of the spectrum, higher-income households may find the rule overly restrictive, as their financial priorities center more on wealth building than strict percentage splits.

Housing and Healthcare Costs Outpace Budgets

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports that in many metropolitan areas, housing alone consumes 35–50% of income. When healthcare premiums, deductibles, and transportation costs are added, families often surpass the 50% “needs” threshold before considering groceries or insurance. This makes the model unrealistic for those living in ultra high-cost regions such as New York, San Francisco, or Los Angeles, where even median earners struggle to keep rent below recommended limits.

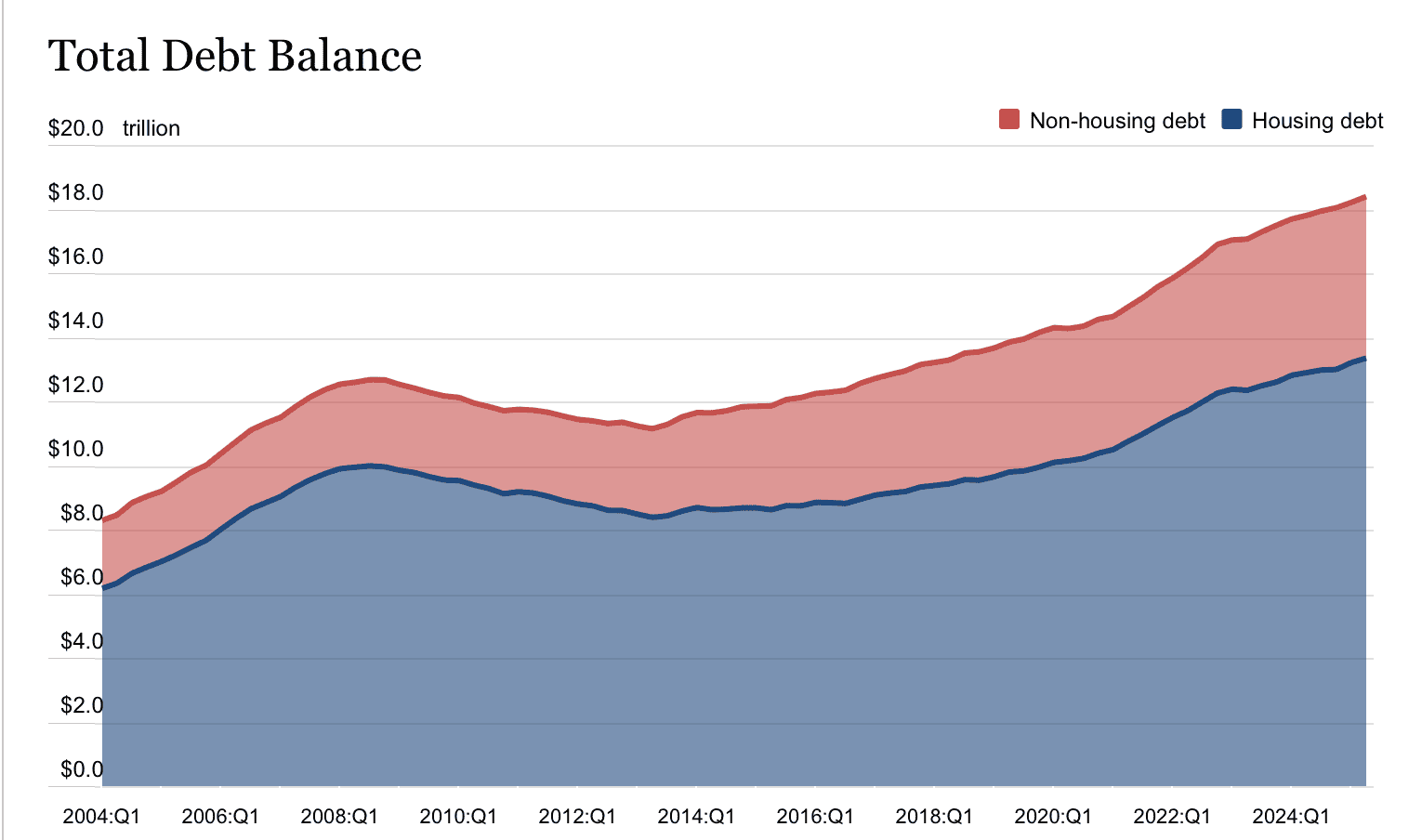

Debt Overwhelms the Savings Category

According to the Federal Reserve’s Household Debt and Credit Report, credit card balances, auto loans, and student debt weigh heavily on U.S. households. In theory, 20% of income should go toward savings and debt repayment. In practice, many families use the entire 20%, and sometimes more, just to service debt, leaving nothing for long-term savings or emergency funds. The trade-off is financial stagnation, where even diligent efforts to follow the model result in little progress.

Source: FRBNY

Irregular Income Creates Instability

Freelancers, gig workers, and part-time employees, an increasingly large share of the workforce, face fluctuating monthly income. A fixed-percentage rule offers no flexibility when earnings swing widely from one month to the next. For someone who earns $2,500 one month and $4,000 the next, allocating a flat 50% or 20% does not necessarily reflect their financial realities or obligations. Instead of simplifying finances, the rule can add stress for those without steady paychecks.

Blurred Lines Between Wants and Needs

Financial literacy studies reveal that many people struggle to distinguish between “wants” and “needs.” Is internet access a necessity or a luxury? Is dining out a want, even if it’s the only viable option during long work hours? In today’s digital-first economy, items once considered optional, like smartphones, are now essential for work, education, and communication. This ambiguity undermines the rule’s usefulness and highlights how subjective financial categories can be.

Behavioral Economics Exposes Flaws

Behavioral research shows that rules-of-thumb only succeed when paired with accountability. Without active expense tracking, people often underestimate discretionary spending and assume the percentages balance themselves. The illusion of following the rule can lead to overspending, complacency, and financial shortfalls.

When the Rule Still Has Value

The 50/30/20 budget isn’t completely irrelevant. For households with stable incomes, manageable housing costs, and low debt, it can serve as a helpful entry point into financial planning. It provides a framework for thinking about balance, ensuring that money isn’t entirely consumed by either lifestyle upgrades or debt payments. In this context, the rule works less as a strict formula and more as a reminder to prioritize savings and limit lifestyle creep.

Smarter Alternatives to Consider

70/20/10 Rule

A more flexible option in high-cost living areas, this version combines essentials and discretionary spending into 70%, reserves 20% for savings, and allocates 10% for debt. It acknowledges that fixed costs often exceed 50% while still ensuring long-term priorities remain funded.

Zero-Based Budgeting

This system requires assigning every dollar to a specific purpose, whether bills, savings, or discretionary spending. It’s particularly effective for those with irregular incomes because it adjusts monthly and forces intentional spending decisions.

Needs-First Budgeting

Rather than starting with fixed percentages, this method prioritizes covering essentials first. Only after food, housing, utilities, and healthcare are paid does the budget allocate to savings and wants. This avoids the unrealistic assumption that everyone can cap their needs at 50%.

Bottom Line

The 50/30/20 budget rule endures because of its simplicity, but financial reality is rarely simple. Rising housing, healthcare, and debt burdens have made it impractical for many households. While it can work as a loose guideline for some, relying on it rigidly often sets people up for frustration. A personalized, flexible approach that reflects actual income, debt obligations, and cost of living is far more effective. In today’s economy, financial resilience requires adaptation, not adherence to a decades-old formula that doesn’t reflect modern realities.